Sykes-Picot and the right to self-determination

One day in the capital of the grand old British Empire, Foreign Secretary Sir Arthur Balfour and diplomat Sir Mark Sykes sat down to discuss how best to preserve their interests in the Middle East with the then imminent fall of the Ottoman Empire.

"What sort of agreement would you like to have with the French?" Balfour asked.

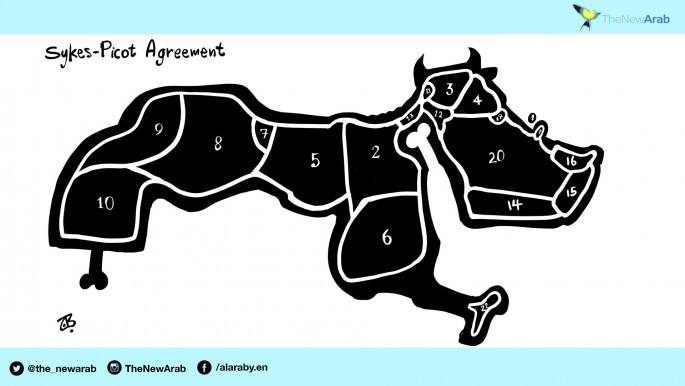

"I should like to draw a line from the 'e' in Acre to the last 'k' in Kirkuk," Replied Sykes, whose unceremonious response had little more regard for the matter than if the colonel had been asked how many spoons of sugar he preferred in his tea.

With that, however, the fate of millions was decided, with little regard for the diverse ethnic, religious, and linguistic milieu that characterises the Middle East.

The agreement was made in secret between the British and the French, only to be outed two years later when Lenin discovered its details in the cabinets of the deposed Tsarist regime.

Today, the region still reels from this legacy of ham-fisted imperialism, with visions of a post-Sykes-Picot world still remaining foggy.

New world, old tactics

A hundred years after the agreement was made, for the Western powers much remains intact. Britain, although now empireless, still conducts its business of government from the cabinet room in which the Balfour and co handled their imperial outposts, enjoying the stability of a parliamentary democracy that was and still is.

|

|

| The carving up of the Middle East [TNA] |

Indeed, for the Arabs, Kurds, Armenians and numerous other ethnic groups who make up the Middle East, the picture could not be more different than that of their former imperial masters.

Enter a resurgent Turkey, Russia and Iran, and it seems that the fate of a region torn by civil strife and terrorism is still out of arms reach for the very people that live there.

Tearing down the old order

Due to the patchwork of ethnic and religious minorities who were forced together by the 1916 agreement, the fragility of the region has largely been kept in check by iron-fisted rulers whose divide and conquer tactics have done little for the progress of the region and its peoples.

The Arab Spring revolutions of 2011 offered a glimmer of hope with the fall of many of Western-backed dictators who maintained the uneasy semblance of peace in countries like Iraq.

Fast forward to 2016, however, and the neo-colonial murmurings that the Arabs are "not ready for democracy" can still be heard, with voices of moderation from the region drowned out by extremes of violence.

When the Islamic State group destroyed the border posts seperating Iraq and Syria in 2014, it did so while defiantly declaring an "end to the Sykes-Picot era."

Far from being an end to the era, however, the current predicament that the Middle East's faces is still one of self determination in the face of continued imperial puppeteering, helped by the extremes of ethnic and religious violence.

Indeed, while the Western coalition fighting the IS group have found the Kurdish fighters to be among the most effective allies against the jihadists, the 25-30 million Kurds remain the world's largest stateless people - a lasting legacy of the Sykes-Picot agreement.

And while Kurdish groups have threated to declare an independent state of their own, many of the world powers involved in Syria and Iraq's fallout seem unable to envision an alternative future in which the current boundaries may have to be abandoned.

Today's relevance

While mentions of Syke-Picot have become somewhat tiresome in contemporary discussions of the Middle East's past and future, its relevance to the modern debate must not be forgotten.

The legacy of imperial engineering must not be forgotten in a time when the voices of millions of Arabs, Kurds and others have been drowned out by the violence that has engulfed the region after 2011's uprisings.

It may indeed be the case that the Middle East needs a new cartography. However this painstaking process must not be done from outside, as the last 100 years of history shown.

The new Middle East must take shape from within the towns and capitals of the Middle East, and not the capitals of the world's rival powers.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News