Clubhouse - the social media app keeping Iranians up all night

The audio-chat platform has some distinctive features: It is optimised for diversity and conversation rather than popularity and division, and it builds a real and live audience rather than a shapeless group of followers.

For a few weeks now, hundreds of thousands of Iranians have been spending many hours listening to serious and lively, yet civilised, discussions on burning matters of the day, such as the upcoming presidential elections, the possible revival of the Iran nuclear deal, the future of democracy, as well as sexual misconduct by renowned male figures.

Last week, these interests all converged in a town hall-type discussion with a well-known activist, Faezeh Rafsanjani, daughter of a former president. The Clubhouse room not only filled to its maximum capacity of 8,000 participants, but also packed a whole separate room where the main audio feed was rebroadcast live. All the while, thousands of others were listening in on a new Twitter audio chat feature called Spaces.

|

Success on Clubhouse means being inclusive - enough to attract diverse people with opposing views rather than preaching to the converted |  |

For over five hours, the outspoken activist who is best known for her tireless efforts in the 1990s to get the male-dominated regime to allow women-only sports, took dozens of difficult questions from a wide range of participants. Iranian foreign minister Javad Zarif, and the head of Iran's nuclear energy organisation Ali Akbar Salehi, have also addressed full rooms in similar town hall discussions in recent weeks.

Clubhouse and its non-patriarchal architecture

So what makes Clubhouse, and the conversations happening there so diverse, civilised and decidedly non-patriarchal? It comes down to a simple idea: No to the 'like' button.

Eliminating the 'like' button, a now ubiquitous feature of all social media platforms, has made Clubhouse feel like blogs again. The text-heavy blogosphere, which dominated Iran's online public space in the mid 2000s, was based around hyperlinked cross-posts and lively comments sections which inherently encouraged diversity and conversation. Iran in those days had one of the highest number of bloggers worldwide, with nearly half a million Persian blogs, mostly hosted by native blogging platforms.

However, the emergence and quick dominance of a new generation of platforms such as Facebook - also known as Web 2.0 - and the invention of 'like' buttons in the early 2010s came to present a clear departure. Blogs were gradually abandoned and their authors flocked to Facebook and Twitter to voice their opinions.

Those 'like' buttons incited a toxic environment for uncivilised competition, where alpha-male types succeeded, and everyone else - often women and minorities - was easily marginalised and harassed, unless they too, gave in to this patriarchal game of chicken. The more extreme you sounded, the more likes, retweets and shares you racked up, the more you helped platforms know their audience, and sell them to advertisers.

|

|

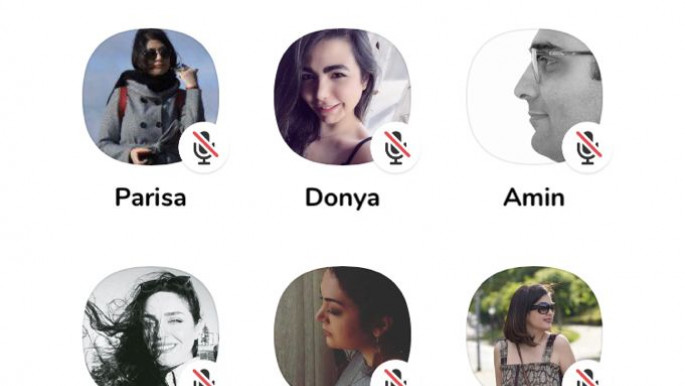

| A screenshot of the Clubhouse room: 'Clubhouse in the past week' |

Clubhouse, by design, does not allow any engagement with other speakers or participants unless you raise your hand and moderators give you the chance to speak, using your own voice, and usually your real identity.

Read more: Oman blocks Clubhouse, app used for free debate in Middle East

You cannot ridicule or harass speakers by sending them nasty comments or emojis in private or in public. You cannot mention, quote or troll others the way you can on other platforms, especially Twitter. You can still verbally harass people, but you will appear anti-social, or risk being muted or blocked by moderators who often behave much more justly and politely than they do outside this role.

American sociologist, Irving Goffman, has famously theorised social life as a theatre with an on-stage, where people try to present the best version of themselves by adhering to dominant social norms, and a back-stage, where social norms are not observed because there is no audience to perform to.

While Clubhouse creates a stage where speakers and moderators feel the real and live presence of an audience, other platforms like Twitter encourage back-stage behaviour because their audience - called 'followers' - is neither live nor necessarily real, and therefore rarely felt. As an avid Twitter user with over 50,000 followers, I never feel stressed when I tweet, but on Clubhouse, I always sweat when I have to speak.

Unlike other platforms, success on Clubhouse means being inclusive - enough to attract diverse people with opposing views rather than preaching to the converted. Sessions with homogenous participants quickly feel boring and repetitive and their audience shrinks. What differentiates it from the conventional broadcast talk show format, is that Clubhouse sessions are not confined to short time slots, and most last hours longer than anticipated.

Impact on Iranian elections

Iranian society, like many others, has grown very divided along generational, gender, and class lines in the past two decades, since the reformists rose to power.

The public sphere, dominated by Iranian state media on the one hand and foreign state-sponsored Persian media run from the US, UK, Israel, and Saudi Arabia on the other, is bifurcated between extreme anti- and pro-regime discourses, with little middle ground and few bridges.

|

Clubhouse's addictive appeal also lies in all those mid-size rooms where pro- and anti-regime activists and journalists can meet |  |

Social media platforms such as Twitter or Telegram, both officially blocked by the regime but accessible through VPNs, function more as extensions of these television channels rather than as separate platforms, echoing the two extreme discourses. Instagram, not yet blocked, has largely remained apolitical, dominated by celebrities.

In this context, Clubhouse has burst onto the scene as an exception. Famous politicians' town hall discussions aside, Clubhouse's addictive appeal also lies in all those mid-size rooms where pro- and anti-regime activists and journalists can meet.

The very people who would totally ignore or troll each other on Twitter day and night, now wait for hours in long queues to speak for two minutes after listening to others for hours. The reality of all those round icons with smiling faces belonging to people with long histories of hostility towards each other, patiently waiting and passionately discussing matters of the day, feels like a utopian fantasy.

|

The very people who would ignore or troll each other on Twitter, now wait for hours in long queues to speak for two minutes after listening to others for hours |  |

Women's growing presence and involvement in Clubhouse discussions - especially those moderated by women - points to another advantage of the app's structural differences as compared to other platforms. The absence of features such as private messaging or 'like' buttons, combined with presence of live and real audiences as opposed to a shadowy gang of followers, means women are much more willing to take part in public discussions on social and political matters alongside men on Clubhouse.

Dozens of sessions with hundreds of participants have taken place in the past weeks discussing sexual misconduct by male celebrities, which in some cases has led to public apologies and incited television news coverage.

To many, the June election in Iran remains uninspiring, in part because of how Iran nuclear deal talks are affecting who may or may not run. But the less-patriarchal architecture of this new app is keeping many Iranians up all night.

It would be naive to think Clubhouse conversations can change views and values, but it certainly humanises opponents and moderates their mutual harsh feelings. At a time of growing divisions and inequalities around the globe, this may be good news for other societies too.

Hossein Derakhshan is an Iranian-Canadian author and media researcher, as well as a pioneer of blogging, podcasts and tech journalism in Iran, over which he spent six years in prison. Now based at LSE, He spent 2018 on two research fellowships at the Harvard Kennedy School and MIT Media Lab.

Follow him on Twitter: @h0d3r

Have questions or comments? Email us at editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News