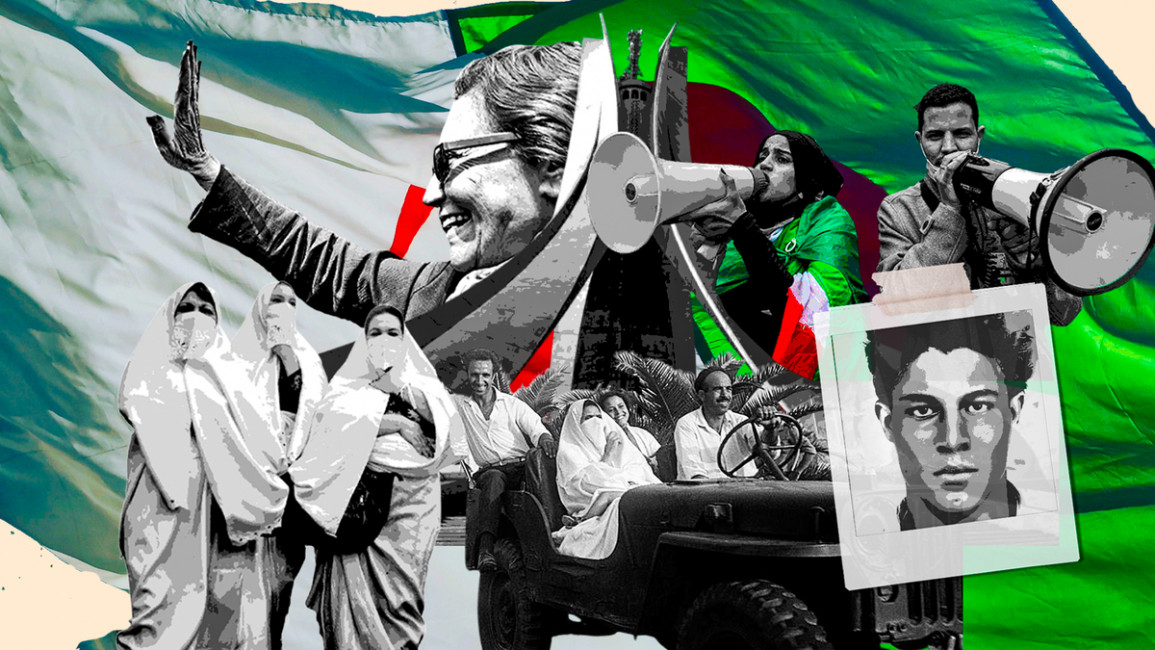

The people are the heroes of Algeria's 61 years of independence

This year is the 61st anniversary of the hard-won independence of Algeria from French colonial rule. The important event is a painful reminder for me that my three children have never known their grandfather who was a lieutenant in the Algerian armed resistance. This is because when I was just four years old, he and his platoon were ambushed and killed by the colonial forces.

French colonial rule in Algeria, which began in 1830, lasted 132 years. It was after a harrowing eight-year war (1954-1962), which ended with the ratification of the Evian Accords, that Algeria won its independence on 5 July 1962. At least 1.5 million Algerians are believed to have been killed.

61 years ago, Algerians expressed their joy and jubilation to see the end of French colonialism. They sang and danced in every corner of the country while commemorating the ultimate sacrifice of the martyrs. They knew then, as we still know now, that there was one hero: the people.

''Ordinary Algerians on the other hand, have never asked and will never ask France for an apology. They know that they fought a hard, long war to achieve an independence that they ultimately won.''

Indeed, the two decades that followed were Algeria’s golden days. The people who defeated French colonial rule became an impetus for many liberation movements around the world. Amilcar Cabral, Africa’s staunch anti-colonial leader, famously declared Algeria, “the Mecca of revolutionaries.” Even the Black Panther Party had representatives stationed in Algiers at some point.

But subsequent events would engender a myriad of corrupt and incompetent military high ranking officers and apparatchiks who not only confiscated independence, but seemed to make it their raison d'être to replace the coloniser/settler. The end result is the current calamitous socio-political situation.

During the war of independence, Abbane Ramdane, one of the Algerian revolutionary leaders, called for “the prevalence of the political over the military.” But other military leaders in the National Liberation Front (FLN) vetoed Abbane’s call and physically eliminated him. This was, according to some historians such as Mohamed Harbi and Benjamin Stora, the beginning of power grab and the origins of military power in Algeria.

In June 1965, Colonel Houari Boumediene, who was serving as defence minister, and who never took part in a single battle against the coloniser during the revolution, toppled the country’s first civilian elected president, Ahmed Ben Bella.

Boumediene’s private secretary in his hideout in Morocco, Abdelaziz Bouteflika – who later would become president – played a critical role in the coup d’état in June 1965 and became one of the architects of the Algerian tyrannical regime.

With Boumediene and his putschist enablers, the political was subdued by the military. His oppressive presidency lasted until his death in 1979. But his Egyptian model of military rule with a civilian façade still persists.

Boumediene’s economic model was what he once termed “Algerian socialism.” Yet on the ground the people were suffering due to scarcity of basic foods and long queues for imported commodities, and the first Algerian billionaires emerged in the shade of Boumediene’s state capitalism.

While the decision-makers and their clientele got richer, and FLN apparatchiks monopolised every inch of power, unemployment soared. Then, with the tumbling of oil prices in he mid-1980s, the government cut various subsidies that triggered the mass protests of 5 October, 1988.

To take the edge off dissent, the regime was forced to open up the political scene. For the first time, the authorities allowed privately-owned and independent newspapers, banned political parties were reauthorised and new ones were approved, exiled political figures returned home, and the one-party system led by the FLN became a thing of the past.

In June 1990, in the first free elections since independence, the Islamic Salvation Front (FIS) swept the local elections with 54% of votes cast. And in December that year, the FIS won the first round of the parliamentary elections. It was obvious that the FIS would get the majority in the second round also. However, the military soon stepped in, and in the name of “preserving democracy,” they put an end to the democratic process, and jailed thousands of Algerians.

Today, Algeria marks the 61st anniversary of its independence. In the picture, it is mentionnd that there is "Only one hero, the people" #Algeria . pic.twitter.com/dbYrEbMCyX

— MA. Bouanzoul, MD (@MBouanzoul) July 5, 2023

The consequences of this was a decade-long civil war which claimed the lives of more than 250,000 people. This was then followed by the 20-year despotic reign of Abdelaziz Bouteflika who meticulously applied himself to reinforce the system that the powers that be – aka le pouvoir in Algeria, wanted in place.

Bouteflika’s absolutism encouraged nepotism, embezzlement, and a widespread high-level corruption. By some estimates, more than a trillion US dollars of oil revenues were stolen and/or misused during his presidency. To add insult to injury, his protégés invested millions in France which his cabinet ministers never missed an opportunity to ask France for repentance and an apology for the crimes committed against the Algerian population during the colonial rule.

Ordinary Algerians on the other hand, have never asked and will never ask France for an apology. They know that they fought a hard, long war to achieve an independence that they ultimately won.

When Bouteflika decided to run for a fifth term in 2019, it was the straw that broke the camel’s back. Millions of young men and young women took to the streets of cities big and small to say barakat - enough is enough. That protest movement known as the Hirak precipitated the ousting of Bouteflika.

The current president, Abdelmadjid Tebboune, whose election in 2019 is still debatable, has proclaimed a “new Algeria” and instigated a series of measures to stamp out bureaucracy, eradicate corruption, and encourage local and foreign investment. The results so far, however, have been meagre.

He has dramatically failed to contain unemployment which is leaving young people with no choice but to partake in dangerous migration to the West. Furthermore, his skimpy reforms are eclipsed by a crackdown on freedom of expression and freedom of the press. Some 250 political activists and Hirak protesters are still in jail. But the disenchantment that triggered the protests still remains and ordinary Algerians still want to get rid of the regime.

This desire is best captured by a young Hirakist who precipitously walked into the live shot of a Sky News Arabia journalist in 2019, and asserted in Algerian dialect, “Yetnahaw gaa” - they have all got to go. An idiom claiming the removal of all those who confiscated the Algerian independence and the will of the people.

Dr. Abdelkader Cheref is an Algerian academic and a freelance journalist based in the US. As a former Fulbright scholar, he holds a PhD from the University of Exeter, Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies. His research interests are primarily politics in the MENA region, democratisation, Islam/Islamism, and political violence with a special focus on the Maghreb.

Follow him on Twitter: @Abdel_Cheref

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@newarab.com

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News