Salaam, Liverpool: Salah and Mane, the Muslims who saved a club

Liverpool F.C. - which claimed its first Premier League title in 30 years last weekend - boasts two men of the second, and higher order: Mohamed Salah and Sadio Mane, the two soccer savants that spearheaded Liverpool's historic 2019-2020 campaign.

Salah and Mane are Muslims, and unapologetically so. The Arab and Black Muslims were thrust onto a stage - English football - long tainted by anti-Black racism and xenophobia. They traveled distinct journeys en route to Liverpool, and encountered challenges that tested their resolve upon arrival. But their faith provided them both with a common path toward not only overcoming the pitfalls that foiled other footballers, but to transcend on and off the pitch.

Mohammed walks

The Egyptian and Senegalese Muslims could have easily traded in their Muslim identities in exchange for the fast cars and opulent lifestyles footballers in England are infamous for. But in shunning that path, and walking diligently behind their faith's final and foundational Prophet, Mohammed, Salah and Mane lived up to their club slogan of "you'll never walk alone."

While, as one journalist put it, "Death, plague and economic collapse stalked the land, puncturing sport's ability to pretend the rest of the world is simply a subplot," the world of Mohamed Salah and Sadio Mane illustrated - all along - how sport is one of life's most impactful theatres.

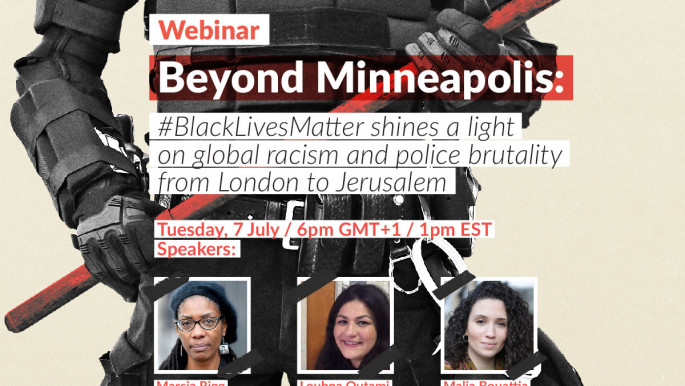

|

| Click to register now - webinar tomorrow! |

The two Liverpool forwards, with Mane flanking the right side of the pitch and Salah dazzling to the left, spearheaded the Club's rise to the top of the table. Liverpool not only won the championship, but thoroughly outclassed the field with a dominating 28 wins compared to only two draws and a single loss, besting runner ups Manchester City by a wide 23 point margin.

Not surprisingly, Salah and Mane led the historic run toward the title, with the "Egyptian King" netting 17 goals and the reigning Africa Player of the Year, Mane, scoring 15. These marks placed Salah as the Premiership's third highest scorer, and Mane as its sixth.

Every time they scored, and they did often, Salah and Mane dropped to their knees and prostrated in the ancient Islamic custom. The prayer, penalised by sports leagues like the NFL, became far more than just a common sight for EPL viewers, but one emulated by Liverpool fans of every faith, inspiring a change in the culture at the 128-year old football club: This historic season, like the several before it, witnessed a steady erosion of the Islamophobia that gripped England, thanks to Salah and Mane's impact.

White men, dressed in Devil red that professed Christian or other beliefs, would regularly explode in the customary song:

Twitter Post

|

"Mo Salah, la, la, la, la, La, la, la, la, la, la,

If he's good enough for you,

He's good enough for me,

If he scores another few then I'll be Muslim too,

If he's good enough for you,

He's good enough for me,

Then sitting in a mosque is where I wanna be."

They sang the refreshingly original chant, and sang it again. In the stands and at pubs, inside their living rooms and anywhere they sat when Salah put the ball in the back of the net.

The juxtaposition was surreal against the Islamophobia fanned by Brexit and Boris Johnson. The scenes inspired by Salah were magical. Everyday Englishmen, women and young people chanted, "I'll be Muslim too" and revelled in the thought of "sitting in a mosque."

The Muslim stars were challenging the Islamophobia that gripped England and the world around it. And the Mane and "Salah Effect" was not just symbolic or anecdotal, but measurable. "Per the Stanford University Immigration Policy Lab, Salah is credited with single handedly reducing Islamophobia and hate crimes in Liverpool since he signed with the club in June 2017."

Specifically, the Stanford University study found that hate crimes in the metropolitan Liverpool area declined by 19 percent, and anti-Muslim comments spiraled 50 percent since Salah joined Liverpool in 2017. Salah's impact is quantifiable, and his on-the-field play and off-the-field presence is changing hearts and minds at a time when nativism has been spiking in England, and Islamophobia proliferating across the world.

Before helping Liverpool claim its coveted Premiership title, Salah championed a new culture of acceptance among football fans, by simply being authentically and uncompromisingly Muslim.

A pillar of humility

As he did for Liverpool's formidable offense, Mane complimented Salah with a new model of the modern football star. In September of 2018, only hours after scoring the decisive goal against Leicester City, Mane drove to the mosque as he always did. There, he was filmed filling water buckets and cleaning the toilets inside the bathroom - where Muslim men washed themselves before the collective prayer.

Unaware of the camera phone locked on him, Mane unassumingly cleaned the space alongside others. The video, showing the footballer cleaning the floor and toilets, later went viral. It instantly won over millions of fans, who lauded Mane for his "otherworldly modesty" and, in line with Islamic principles, "holding himself equal" despite being a millionaire footballer.

Read more: Boris Johnson's police state won't solve the coronavirus crisis

This was precisely who Mane was, and what Islam - unfiltered and untainted - represents: Modesty and humility, and towing a line where each person's foot stands equal to the one beside it – regardless of race or class, status or wealth.

In October of 2019, a year after leading Senegal to its second World Cup appearance, Mane was keen on giving his country and its people even more. When asked by a journalist about his model of modest living, he responded,

"Why would I want 10 Ferraris, 20 diamond watches, or two planes? What will these objects do for me and for the world? "I built schools, a stadium, we provide clothes, shoes, food for people who are in extreme poverty."

Through his philanthropy, Mane embodies the Prophetic model that holds, "He is not a believer whose stomach is filled while the neighbour to his side goes hungry." Like he did on the field of play, Mane let his world-class actions do the talking.

|

They stayed the course. And more importantly, stayed true to who they are as Arab and Black men, and as Muslims |  |

Salaam, Liverpool

This is Liverpool F.C.: A curly-haired Egyptian who drops to his knees in prayer every time he scores, and a Black Senegalese soccer giant whose unassailable superpower is his humility. Champions, who reject the luxury cars and glitz in order to give their "people a little of what life has given" them.

These Muslim men emerged in Liverpool, an industrial English city once ravaged by racial violence and menaced today by neo-Nazis and nativists emboldened by populist agendas that mark Muslims, like Salah and Mane, as targets.

But they stayed the course. And more importantly, stayed true to who they are, as Arab and Black men, and as Muslims. Salah and Mane won over a city and a nation marred by racism and Islamophobia with their play, but will be remembered too, for their transcendent personas and genuine authenticity.

Khaled A. Beydoun is a law professor and author of the critically acclaimed book, American Islamophobia: Understanding the Roots and Rise of Fear. He sits on the United States Commission for Civil Rights, and is based out of Detroit.

Follow him on Twitter: @khaledbeydoun

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News