Egypt's 'warming peace' with Israel

Apologists for the Egyptian government will soon start laying down reasons why Israel is just like any other neighbour, and why the country needs to maintain a strong allied front with Tel Aviv against "the real enemy" - terrorism.

They have in fact been attempting to prepare the Egyptian population for such a proposition by playing up the threat of attacks emanating from Hamas - Muslim Brotherhood allies who ostensibly control occupied Gaza. One Egyptian academic said in a London panel discussion in 2014 that Egypt and Israel would enjoy greater cooperation in the future because they, "share a problem called Gaza".

Normalising relations with Israel for Egyptians has always had its domestic champions, but for the majority of the population that proposition has always been a non-starter. Israel has been the standard antagonist of Egyptian sensibilities since its creation in 1948. That said, since Camp David, the two regimes have been - for all intents and purposes - allies that cooperate regionally, especially on security issues, but also in economics and diplomacy.

The Egyptian government, however, has long borne in mind the prevailing populist positions against Israel - sentiments deepened by the seemingly ever-expanding and audacious human rights atrocities sanctioned by Tel Aviv. Most recently of these has been the 2014 massacre in Gaza, in which hundreds of civilians were killed and 3,000 injured, around 75 percent of whom were civilians.

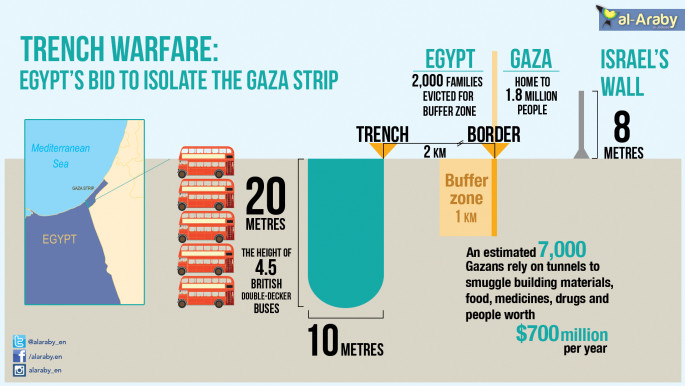

These daily and nightly attacks played out on the world's TV screens, yet the Egyptian government - Israel's fellow jail-guard ensuring Gaza remains under lock and key - did not attempt to apply any real political pressure on Israel to stop the attacks, nor did it attempt to ameliorate the situation faced by ordinary Gazans.

A tawdry call to end the massacre a week after it began was all it could offer.

|

It was the first state visit for an Egyptian foreign minister in nine years, yet it looked like the meeting of old friends |  |

Despite all of the regime's attempts, and those of its apologists, to poison the waters of discourse, many Egyptians were alarmed by the friendliness of last week's visit of Foreign Minister Sameh Shoukry to Israeli Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu.

It was the first state visit for an Egyptian foreign minister in nine years, yet it looked like the meeting of old friends. They watched football together, exaggeratedly exchanged pleasantries, and met in Jerusalem, not Tel Aviv. Shoukry agreed to speak at a press conference with a statue of Theodore Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, staring down upon him.

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

In previous years, intelligence officials and lower-level delegations would make such trips. There were attempts to appear business-like and pragmatic.

Two months ago, President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi clearly stated that he aspired for a "warmer" kind of peace with Israel. He went on to use rhetoric more normally associated with US or European establishment political speeches, equating the pressing need for justice for the Palestinians, with Israel's right to security.

These words are seemingly benign, yet they are the same words that the Israeli government uses when justifying its massacres and its daily infringement on Palestinian rights. It was a sign that finding a lasting solution to Palestinian crisis is no longer a priority. In fact, it seemed to confirm the growing suspiscion that Sisi is a God-send for this Israeli government, a gift that Israeli policy-makers will embrace whole-heartedly.

Some have analysed this visit in light of Cairo's need for increased security cooperation with Israel over armed groups in the Sinai, or in order to appeal to Israel to use its apparent clout with Nile Basin countries to ensure Ethiopia's Renaissance Dam does not damage Egypt's water supply. However, these are diplomatic issues which do not need such ostentatious displays of friendship. Security cooperation and intelligence-sharing has never stopped between the two countries, despite the populist public stances taken by each side over many years of posturing.

Sisi's foreign policy outlook to date would indicate that recent moves have been an attempt to bolster his position regionally in a way that offers his regime more legitimacy - as well as insulation from debilitating criticism of his human rights record.

Perhaps channelling his inner Sadat - who did his best to forge a friendship with Golda Meir - this president believes the best way to be considered a regional power player once more, is through Israel.

It is also a sign - as it was in Sadat's day - that Arab unity, is all but extinct, if it ever existed. The Egyptian regime has lost nearly all of its political leverage vis-à-vis Saudi Arabia and the UAE, which it has been blundering around fishing for grants, financing and investment, to the point of agreeing to cede islands to the Saudis.

|

It seems as though Cairo erroneously believes it still enjoys enough political capital to make extremely unpopular decisions |  |

This is a way for Sisi to get back in the game without directly butting heads with his benefactors. He also needed to make this move quickly as his nemesis, and fellow Israel-normaliser Recep Erdogan, just did the same thing a couple of weeks earlier.

Domestically, it seems as though Cairo erroneously believes it still enjoys enough political capital to make extremely unpopular decisions without much fear of public fallout. But besides Sisi's administration making unpopular recent budget cuts, the island handover caused uproar.

The warming relations also beg the question of how Cairo will react the next time Netanyahu decides to "mow the lawn" with atrocities in Gaza or elsewhere.

Given the current turmoil and havoc in regional politics, Sisi's plan may work in the short term to convince Western capitals that he is a trustworthy ally, indispensable in the war on terrorism. It is much less likely that he can retain domestic support for such propositions, with Shoukry's visit already drawing criticism from some regime supporters.

Mohamed ElMeshad is a journalist and a PhD candidate at SOAS, focusing on the political economy of the media. He worked extensively in Egypt, Bahrain, West Africa, the UK and US.

Recently, he contributed to the Committee to Protect Journalists’ book, Attacks on the Press (2015).

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of al-Araby al-Jadeed, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News