As rights violations increase in Egypt, so does British investment

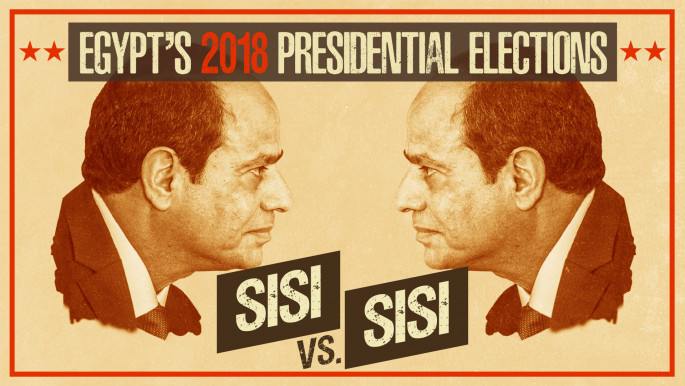

President Sisi's only competitor is a self-declared supporter of the strongman himself, and in the absence of real choice, many Egyptians have pledged to vote with their feet.

As the elections near it's worth considering the UK's relationship with Egypt, particularly given that the British government's consistent failure to take a stand against Sisi has been interpreted by the president as a blank cheque not only to continue violations, but to worsen them.

Among the factors that define UK-Egypt relations, it is the trade deals that really speak volumes about the lack of integrity of certain members of the British government. While Egypt's opposition is being tortured in Sisi's dungeons British authorities are pushing for profit from a cash-strapped country, with very little return for the Egyptian people themselves.

During his time in power Sisi has incarcerated some 60,000 political prisoners which means his rule far outweighs Mubarak's in terms of severity. In 2011 the number of political prisoners numbered somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000.

Sisi has overseen three mass killings, each in response to protesters challenging the role of the army in politics. On 8 July 2013, 61 demonstrators were killed outside the Republican Guard Headquarters. A week later 37 prisoners were gassed inside a police truck, and let's not forget the Rabaa massacre in which over 1,000 Egyptians were slaughtered in the streets in a single day.

|

The UK has paid Sisi $500,000 for every pro-democracy supporter he has imprisoned |  |

It's really the response of British politicians to the Rabaa massacre that laid bare the UK and Egypt's relationship - as Egyptians scrambled to bury the dead before they were punished by association, then foreign secretary William Hague said he was "deeply concerned".

As the Rabaa anniversary rolls round each year, with barely a mention, Britain may have forgotten the tragedy of what happened that day, but the families of the victims have not. Hague's weak statement was nothing short of outrageous.

|

|

It's becoming increasingly clear that what Hague was deeply concerned about that day, was what would happen to British multinationals if he took a real stand on the massacre.

One way the UK could do this would be to use their economic leverage over Egypt, for example by conditioning foreign investment on a promise to abide by the rule of law.

In 2016 British investment in Egypt hit $30 billion. Instead of forcing Egypt to stop violating human rights the UK has paid Sisi $500,000 for every pro-democracy supporter he has imprisoned.

It's not just the weak statements issued by members of the British establishment. It's that since the Rabaa massacre Britain has pushed even harder for trade deals with Egypt.

In the four years after this tragedy Britain licensed $172 million worth of arms to Egypt, whereas in the four years before that this figure was closer to $106,000.

Read more: Egypt authorities 'committing mass suicide' warns Nobel Laureate amid growing election crackdown

British Ambassador to Egypt John Casson has said he's "hungry for more" investment and former Middle East Minister Tobias Ellwood returned from Egypt, having visited with a large trade delegation, and said that he couldn't recall if he raised the issue of human rights when he was there.

|

Sisi is desperate for foreign investment so they're getting some pretty sweet deals |  |

In 2016, two weeks after Cambridge University post-graduate student Giulio Regeni's battered corpse was found on the Cairo-Alexandria highway, bearing all the hallmarks of torture characteristic of Egypt's security services, British trade envoy to Egypt Sir Jeffrey Donaldson visited Egypt and declared it a "land of opportunity for British companies".

It's not difficult to see why British companies are keen to invest in Egypt; Sisi is desperate for foreign investment so they're getting some pretty sweet deals.

In 2015 BP secured a deal to sell 100 percent of the gas produced from two offshore blocks off the coast of Egypt. Traditionally in Egypt the foreign investor's share stands at between 20 and 30 percent.

|

Britain may have forgotten the tragedy of what happened that day, but the families of the victims have not |  |

Former Egyptian MP Hatem Azzam estimated that the BP deal cost the Egyptian people some $32 billion. This really is at the heart of the problem with British investment in Egypt - how much of it is going to fund roads and schools and how much of it is going into the pockets of the wealthy elite close to the government?

Multinationals themselves say the money reaches Egyptians eventually, in the form of jobs for example, but there is no evidence of this. Corruption is on the rise in Egypt.

In 2015 Egypt scored 88 out of 100 on Transparency International's corruption index and in 2016 slipped down to 108. In 2017 they hit 117. Former head of Egypt's anti-corruption watchdog Hisham Geneina said that Egyptian officials squandered some $67.6 billion over four years.

Corruption affects the poorest parts of society and Egyptians are getting poorer. In 2013 26.3 percent of Egyptians lived below the poverty line; in 2015 this went up to 27.8 percent and in 2017 this figure was predicted to hit at least 35 percent.

The situation in Egypt has reached breaking point.

Human rights violations are rising, corruption is rising, poverty is rising. Why, then, are the number of British trade deals in the country rising? It's clear that the UK has no interest in using its leverage to force Egypt to behave, but instead is taking advantage of the turmoil to generate economic return.

Amelia Smith is a London-based journalist who has a special interest in Middle East politics, art and culture. She is editor of The Arab Spring Five Years On. Follow her on Twitter: @amyinthedesert

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News