How UNRWA became a battleground in the struggle for Palestinian rights

It was a huge relief for UNRWA and the 5.7 million Palestinians dependent on its services. The agency's Commissioner-General Philippe Lazzarini welcomed the "renewed UNRWA-US relationship", citing America's decades-long role as the largest supporter of the organisation. The Palestinian Authority also praised the decision and described it as a "victory for Palestinian diplomacy."

Predictably, Israel was displeased. Gilad Erdan, Israel's Ambassador to the US, denounced the decision, decrying "the anti-Israel and anti-Semitic activity happening in UNRWA's facilities," and saying that "the UN agency for so-called 'refugees' should not exist in its current format."

In a parallel effort to derail the decision, a group of pro-Israel organisations - spearheaded by the Anti-Defamation League (ADL), the Orthodox Union, and the Zionist Organisation of America - sent a letter to Congress calling on lawmakers to urge "UN Secretary-General António Guterres to shield students in UN-run schools from lessons steeped in antisemitism and supportive of violence."

Another letter was sent to Biden by Senator Ted Cruz of Texas and 18 other Republican senators urging the administration to pause funding subject to further congressional scrutiny.

|

From day one, UNRWA's core focus was the 750,000 Palestinians made refugees as a result of Israel's establishment in 1948 |  |

To ease Israel's concerns and the Republicans' reservations, Secretary of State Antony Blinken announced that aid to the Palestinians would be in line with congressional restrictions, including laws banning (with a few exceptions) direct assistance to the Palestinian Authority as long as it pays subsidies to the families of Palestinians injured or imprisoned by Israel. Later, the Biden administration also said it had the commitment of UNRWA to "zero tolerance for anti-Semitism, racism or discrimination."

Liberal pro-Israel group J Street, on the other hand, welcomed the restoration of funds to UNRWA and other financial aid. This includes $75 million in bilateral assistance to the Palestinian people, $10 million for peace-building programmes, $15 million in Covid-19 relief, and $40 million in previously frozen funds to assist Israeli-Palestinian security liaison.

The history of UNRWA

|

|

| Read more: Sheikh Jarrah and the ethnic cleansing of Palestinians in East Jerusalem |

UNRWA was established as a subsidiary body of the UN General Assembly in December 1949 and became officially operational in May 1950. From day one, its core focus was the 750,000 Palestinians made refugees as a result of Israel's establishment in 1948.

Up until December 1949, the emergency relief of Palestine refugees was carried out mainly by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and other smaller humanitarian organisations, such as the League of the Red Cross Societies (LRCS) and the American Friends Service Committee (AFSC).

UNRWA's mandate covers five main regions of operation: the Gaza Strip and West Bank, Jordan, Lebanon, and Syria. Palestinian refugees outside of these geographical designations are the responsibility of the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR).

The mandate also includes those displaced by the 1967 war and subsequent hostilities, as well as relief efforts for poor persons/families who don't fit the criteria of Palestinian refugees but live in UNRWA's five regions of operation.

The refugee status assigned to the 750,000 Palestinians who lost their homes and livelihood in 1948 has also been transferred to their descendants, currently estimated at over five million. A trans-generational organisation, UNRWA's history, geography, and mode of operation has made it almost synonymous with the Palestine question. This is why the agency's financial security, or lack thereof, has always been intertwined with the core politics of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

|

A trans-generational organisation, UNRWA's history, geography, and mode of operation has made it almost synonymous with the Palestine question |  |

Financial crisis

By the end of 2019, UNRWA operated over 700 schools employing approximately 20,000 staff, ran 141 healthcare centres employing 2,986 health professionals, and provided a social safety net to more than 270,000 families. The annual budget for such a programme, representing the so-called "essential core services," exceeded $800 million, out of a total annual budget just shy of $1.4 billion.

Despite frequent appeals for donors to make up the gap left by the US, the agency still failed to meet its designated annual budget for 2019 and 2020. In 2019, a $211m deficit was projected in UNRWA's $1.2 billion budget, less than half of 2018's $446m budget gap, which nearly forced the agency to close its hundreds of schools and health centres. Further intervention by donors in 2020 reduced the deficit to $130 million, but the threat to the agency's services continued, especially since the Covid-19 crisis in early 2020.

The Trump administration had justified the decision to defund UNRWA on the grounds of economic concerns, expressing unwillingness to "shoulder the very disproportionate share of the burden" of funding the agency, whose operation was "irredeemably flawed."

Germany's Foreign Minister, Heiko Maas, was quick to comment that the loss of UNRWA "could unleash an uncontrollable chain reaction," stressing the agency's role in maintaining stability in the region. He vowed that Germany would step in to make up some of the budget deficit but without specifying the amount.

Regional stability entails fears over upheaval not only in the occupied Palestinian territory (oPt), but also in neighbouring countries with large Palestinian refugee populations. Jordan, for example, which hosts at least two million registered Palestine refugees, is especially vulnerable to changes in UNRWA's status quo.

Already burdened with high unemployment rates and widespread poverty, the country would be unable to cope with replacing the services provided by UNRWA, a situation which could eventually destabilise the state's institutions. The situation would be as dire, if not worse, in Lebanon and Syria.

|

|

| 25 June, 1949: A Palestinian refugee camp near the Dead Sea in Jordan. [Getty] |

Right of return

The move to defund UNRWA had been viewed by many, especially the Palestinians, as an additional intervention on the part of the Trump administration in Israel's favour; another step in a trend that started with the declaration of Jerusalem as Israel's capital a year earlier, and later, the annexation of the Golan Heights.

The administration also backed the Netanyahu government's proposal to annex large swathes of land in the occupied West Bank. The aim was to unilaterally shape the "final status" solution in Israel's favour. Defunding UNRWA, as a final result, would mean taking one of the most critical issues off the table in any final status solution: the right of return for Palestinian refugees.

The US was initially a primary supporter and the largest funder of UNRWA, with a promise that its creation would eventually lead to the implementation of the 1948 UN Resolution 194, which called for the unconditional return of Palestinian refugees to the towns and villages from which they fled or were expelled due to Israel's establishment.

For Israel, the return of Palestinian refugees represents an existential threat, not least because it could end a Jewish majority in the Israeli state, hence Israel's continuous denial or misrepresentation of the 1948 Palestinian mass exodus, otherwise known as the Nakba, or 'catastrophe'.

|

The agency's financial security, or lack thereof, has always been intertwined with the core politics of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict |  |

Israel's anti-UNRWA activities have existed for decades, but were often selective and conditional, fearing that a full dismantlement of the organisation would bring wide-scale chaos and instability, which Israel may fail to contain. At least publicly, consecutive American administrations were also unwilling to indulge Israel's desires to limit the organisation's operations.

However, it was reported throughout successive peace negotiations that US officials have pushed Palestinians to give up or make the right of return symbolic. During the 2000 Camp David negotiations, then Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak suggested he was willing to accept no more than a token return of a few thousand refugees under a 'family reunification programme.' Refused by the Palestinians, then US President Bill Clinton instead put forward a compromise that limited the right of return to a Palestinian state only, which Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat also refused.

By defunding UNRWA, the Trump administration officially embraced Israel's antagonistic position toward the agency. According to Haaretz, the US adopted Israel's "conceptual objections to the Agency, including how it chooses to determine who is and is not a refugee. Operational reforms, no matter how extensive, would not satisfy these demands."

After the defunding was announced, US Ambassador to the UN, Nikki Haley, questioned the number of Palestinian refugees, accusing the UN of 'over-counting' them. On another occasion, Haley also disparaged the right of return as a precondition for any peace agreement between Israel and the Palestinians. Asked whether the issue should be "off the table," Haley replied: "I do agree with that, and I think we have to look at this in terms of what's happening [with refugees] in Syria, what's happening in Venezuela."

|

|

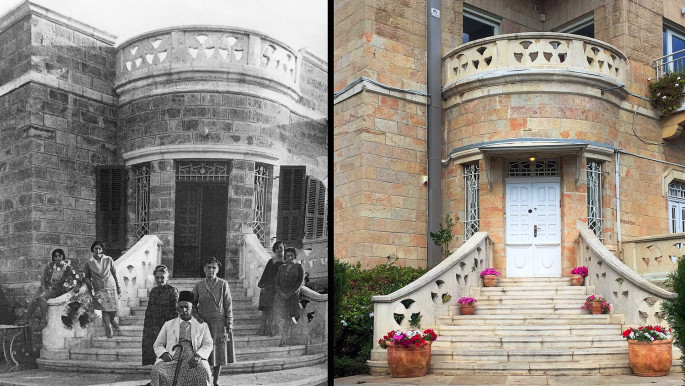

| Read more: 'We were and are still here': A visual history of Palestine's lost past |

Similarly, senior Trump advisor and son-in-law, Jared Kushner, associated UNRWA with the perpetuation of the status quo. In an article by Foreign Policy on 3 August, it was revealed that Kushner said in a series of emails to US officials, including Donald Trump and his Middle East Peace Envoy, Jason Greenblatt, that, "It is important to have an honest and sincere effort to disrupt UNRWA […] UNRWA perpetuates a status quo, is corrupt, inefficient and doesn't help peace," he added.

According to Palestinian officials, in his trip to Jordan in June 2018, Kushner also pressed Jordan to strip more than two million Palestinians of their refugee status, therefore ending UNRWA's operations there.

By protecting Palestinian refugees for over seven decades, Kushner seemed to suggest that UNRWA had kept their hope of return alive, and therefore heightened the zero-sum nature of the conflict; that is, no negotiations or peace without resolving the refugee issue. The pro-Israel camp are particularly critical of the fact that granting refugee status is not just to those who fled Mandatory Palestine in 1948, but to their descendants as well. This eternalises the right of return, thus preventing any breakthroughs in the conflict, they argue.

UNRWA indeed requires reforms to accommodate the current Palestinian reality, but it cannot be blamed for the Palestinian refugee problem, argue Elisabeth Marteu and Sarah Fouad Almohamadi from the International Institute for Strategic Studies. The agency "has never been the cause but rather the symptom of the Israeli-Palestinian stalemate," they write.

|

The return of Palestinian refugees represents an existential threat, hence Israel's continuous denial or misrepresentation of the 1948 Nakba |  |

Limping back to the stagnant status quo

The Trump administration, to cite Haaretz, "fulfilled some of the most fantastical dreams of the right-wing pro-Israel camp, and the Biden Administration is beginning to walk them back." By restoring aid to Palestinians, and UNRWA in particular, the US is returning to its conventional position on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. The question remains, was that position ever sufficient to begin with?

It goes without saying that returning to the pre-Trump status quo serves the United States' interests, which oftentimes encompass those of Israel. In Antony Blinken's words: resuming aid to the Palestinians "serves important US interests and values" as "a means to advance towards a negotiated two-state solution." He added: "It provides critical relief to those in great need, fosters economic development and supports Israeli-Palestinian understanding, security coordination and stability".

|

|

| Read more: How Israel is using the nation-state law to perpetuate racial segregation |

The restoration of aid prevents Palestinians from slipping into acute socio-economic deprivation, which could lead to regional instability and violence. But by keeping Palestinian deprivation at bay, the Biden Administration ensures Israel's security as well. Returning to the status quo with almost nothing new to contribute means, among other things, reinstating the political stagnation that prevailed for decades prior to Trump.

Signs so far indicate that the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is at the bottom of Biden's list of priorities. Unlike former president Barack Obama and Trump, Biden is yet to name a special envoy for 'Middle East peace'. Also, unlike Clinton, Biden has no plans for any sort of peace conference, or even a peace process, anytime soon.

With that considered, the resumption of funding may be understood by some as a 'security valve' to keep the situation from completely breaking down, at least temporarily. In fact, such an objective confirms the fears of some Palestinians who were already sceptical about UNRWA's role.

To them, the organisation has been inimical to Palestinian self-determination, as it created a culture of dependency and systematically de-politicised the Palestinian cause, transforming it into a perpetual humanitarian crisis vulnerable to financial blackmail. Some argue that UNRWA, therefore, has trapped Palestinians in a limbo state of no-peace/no-war, reducing their ability to both organise political resistance or reach their full potential.

Dr Emad Moussa is a researcher and writer who specialises in the politics and political psychology of Palestine/Israel.

Follow him on Twitter: @emadmoussa

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News