China's Uighurs: A genocide in the making

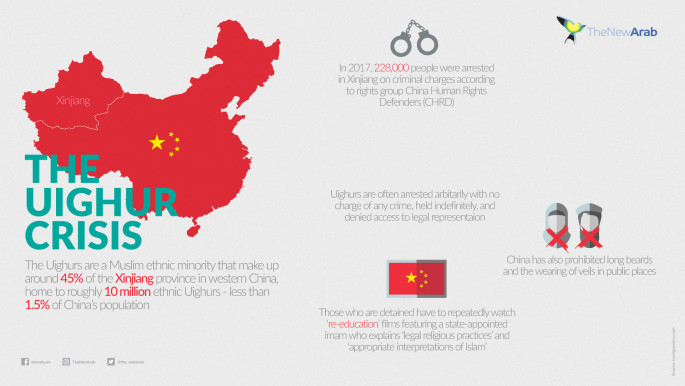

A large portion of the China's ethnic Uighur population is being held in internment camps while the rest of the world watches.

As an effort to understand the long-standing persecution and detainment of Uighurs and the multilayered surveillance state China has implemented in its Xinjiang region, let's break it down to some overarching chapters:

Also spelled as Uygurs, Uighurs, or Uigurs, the Turkic-speaking ethnic group has resided in China's western Xinjiang region for a millennia.

The Cultural Revolution saw a determined Communist China that seeded out those not kind to the state's strict secular reinforcements. The wider political frame of a post-9/11 world gave China the convenience of labelling any Uighur as a potential terror threat, even though the ethnic group has little to no history of radicalisation.

In 2018, it was estimated that 800,000 members of the 11 million Uighur population were detained. In April 2019, the Council on Foreign Relations reported the number had been raised to one million. Since then, reports have further raised the number to two million.

The initial report came out in 2018, but Uighurs have been held in these camps since 2014, when the Chinese Communist Party officially announced the "people's war on terror" and the "strike hard" campaign – which really meant mass police raids – in Uighur neighborhoods.

The Chinese government's heavy-handed response to the July 2009 Uighur riots led to military action and detainment of protesters. That year, nearly 10,000 Uighur protesters went missing.

Some Uighur dissenters have formed attacks against ethnic Han Chinese, creating a gateway for the mainland to label all Uighurs as potential terrorists.

|

|

| Explainer: China's persecution of Uighur Muslims |

China's Cultural Revolution and its subsequent communist control led to a decrease in the presence of mosques, but Uighurs and other Chinese Muslims slowly rebuilt and resumed traditional Islamic practices, particularly in the 1980s and 90s.

One such monumental place of worship, the Keriya Aitika Mosque, disappeared in late 2017. The mosque dates back to 1237; now, it cannot be found via satellite images as a levelled patch of land eerily sits in its place.

When a reporter visited Hami, located in Xinjiang's Yizhou District, an intelligence agency officer informed him that more than 200 of the over 800 mosques just in that region were demolished in 2017; 500 more were set for demolition in 2018.

|

One such monumental place of worship, the Keriya Aitika Mosque, disappeared in late 2017. The mosque dates back to 1237; now, it cannot be found via satellite images |  |

Demolishing places of worship doesn't guarantee secularism, so Chinese officials began to confiscate religious materials and implemented a surveillance state in Xinjiang.

Police stations exist every few blocks in the region's capital, Urumqi, and neighbourhoods were either marked as "safe," "normal" or "unsafe," based on categories like religious faith and ethnic background, while biometric data is used to identify and track Uighurs.

What's more, China's Cultural Ministry released a list of what it considers signs of extremism, which includes contacting individuals who live abroad and refusing alcohol in public. When the checkpoints and surveillance technology fulfill their purpose and individuals are identified as terror suspects – a thinly-veiled stamp alerting officials to Muslims who actively practice their religion – they are sent to detention camps.

Beyond the allegiance-swearing ceremonies and removal of Arabic signage, there are countless other ways in which the Chinese government is insidiously threatening Uighur culture. While it's difficult to document every account of mistreatment, it's important to note that the friends and family members of detained Uighurs are speaking up.

We know that China's so-called "re-education programmes" are using brutal indoctrination methods, including torture, to break and reshape the core identities of Chinese Muslims into loyalists of the Communist Party.

|

China's so-called 're-education programmes' are using brutal indoctrination methods, including torture, to break and reshape the core identities of Chinese Muslims into loyalists of the Communist Party |  |

One example involves an ethnic Kazakh man named Orynbek Koksybek who was detained for several months in one of the camps. His experience, as told to the BBC, is nothing short of horrific: "I spent seven days of hell there... My hands were handcuffed, my legs were tied. They threw me in a pit. I raised both my hands and looked above. At that moment, they poured water. I screamed. I don't remember what happened next. I don't know how long I was in the pit but it was winter and very cold. They said I was a traitor, that I had dual citizenship, that I had a debt and owned land."

When Koksybek was sent to another camp, he was told he could leave as soon as he learned 3,000 words of Chinese.

These forced Chinese lessons aim to diminish, or, ideally, on the part of Chinese officials, eradicate the usage of the Uighur language in its entirety.

According to the article, Koksybek's story is similar to others documented by Human Rights Watch, which also include reports of little to no access to medical care and physical and psychological torture.

Often, these accounts come secondhand from family members living abroad, in the United States, Australia, or Canada, desperate for reunification with their relatives, or at the very least, communication that spans beyond the brief and sometimes surveilled exchanges through messaging apps like WeChat.

While we only hear the detailed stories of a few Uighur intellectuals, The Uighur American Association published an essay stating that "386 known cases of intellectuals [have been] interned, disappeared, or imprisoned, including 101 students and 285 scholars, artists, and journalists." Detainees either left the camps in considerably poorer health or – worse yet – didn't leave the camps alive.

|

|

2. Targeting artists, intelligentsia

One such intellectual is Nurmuhammad Tohti, a prominent 70-year-old writer who was imprisoned in a Uighur camp from November 2018 to March 2019, and died there in May 2019.

Tohti had diabetes and a heart condition and was only released when he became immobile. Like many imprisoned Uighurs, news of his death spread only after exiled family members living outside Xinjiang raised awareness of his internment.

|

|

| Read also: Welcome to Kashgar! Where you can sip tea and watch Uighurs be persecuted |

One of his granddaughters, Berna Ilchi, told Radio Free America that she and other family members living in exile in Canada learned of her grandfather's passing 11 days after it happened, through social media.

"The truth is that they put a 70-year-old man, my grandfather, with diabetes and heart diseases inside a concentration camp and they cannot deny this," she said.

Babur Ilchi, Tohti's grandson, reported to Radio Free Asia that his grandmother hesitated to contact family living abroad after Chinese officials reprimanded her for making an international call: "Shortly after the call, my grandma received a message from the Chinese government saying she had answered a foreign call and that that was a dangerous decision... What did she do other than tell us he had passed away? Why should that be met with consequences?"

It is still unclear whether Tohti died in the camp or shortly after being released to in an incapacitated state. However, his story only continues the questions raised by his family.

It isn't just writers like Tohti who are wrongfully imprisoned. It's pop idols who rose to fame through talent competitions and would have otherwise lived rather ordinary lives, only to be detained and re-programmed – marked as perpetrators of possible future extremist behaviour based on ethno-religious status alone.

To name a few: there's the singer referred to as the "Uighur Justin Beiber" and the Uighur poet and musician who died inside a camp; there's Zahirshah Adlimit, the performer who was detained along with his parents. Adlimit, as told by an old friend from a popular talent show, "...embodied so much of what the producers wanted the show to be: a place to showcase singing that was distinctly Uighur while also tapping into more contemporary, popular forms of music-making."

And that is the biggest threat to the Chinese government: anyone who proudly represents what is so "distinctly Uighur," what is so distinctly other, what is so distinctly dangerous to the overarching narrative of Chinese descent and dissent.

|

Knowing fully well that abstaining from eating pork is an essential aspect of being a Muslim, a government official distributed pork to villagers in the city of Ghulja, further pressing Uighurs to align themselves with a universally Han identity |  |

For example, knowing fully well that abstaining from eating pork is an essential aspect of being a Muslim, a government official distributed pork to villagers in the city of Ghulja, further pressing Uighurs to align themselves with a universally Han identity.

3. Self-interest or diplomacy?

In a generally ineffective global address to Uighur detainment, a United Nations Human Rights Council session in July 2019 featured a joint statement signed by 22 majority-Western countries that spoke out against China's actions.

Not a single ambassador represented a Muslim country, and, what's worse, some Muslim countries – such as Egypt, Algeria, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates – joined the 37 ambassadors praising China for its "counter-terrorism and de-radicalisation measures in Xinjiang."

|

|

| Read also: Why Muslim countries are turning their back on China's repressed Uighurs |

China is a major global economic power, which is why Muslim-majority countries with lackluster economies cannot afford to speak up about Uighur imprisonment.

This is really nothing new: countries have often turned away from denouncing China's misdeeds in fear of jeopardising their place in the Chinese economic schema.

In recent years, this fear has escalated due to the glittering promise of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Launched in 2013, the BRI connects over 70 countries across four major continents (Asia, Oceania, Africa, and Europe) through a network of shipping lanes and railroads. It's a "physical and financial" connection to China that mimics the old Silk Road land route and cost the country $900 billion (£635 billion) of investments.

One of the major players in the Initiative is Egypt, a country that relies on China as one of its major investors. This year, reports of Uighur kidnappings and deportations in Egypt have surfaced, leaving 50 families of the roughly 6,000 Uighur Egyptian population. In short, China is using Uighurs as bargaining chips for its infrastructure plan – but it isn't the only country enmeshed in a trade game.

|

China is using Uighurs as bargaining chips for its infrastructure plan |  |

There's also Pakistan, whose lackluster economic history has relied on Chinese partnership, with China pledging $60 million to the growth and development of Pakistan's infrastructure.

Prime Minister Imran Khan claimed he "didn't know much" about China's Uighur problem, even though Pakistan was included in the letter denouncing any criticism of Beijing's measures and the country allowed China to spy on its own Uighur population, all in the interest of preserving a deep and now mutually beneficial economic relationship.

Then there's Turkey, the country that has strong cultural ties to Chinese Uighurs and has consistently criticised a number of China's actions against the Turkic-speaking Muslims. It is one of the very few Islamic countries to acknowledge the full breadth of "torture and political brainwashing" Uighurs are subjected to inside reeducation camps.

Yet, after meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping in July, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan stated that it would be fitting for both countries to "find a solution to this issue that takes into consideration the sensitivities on both sides." Take note that Erdogan's remarks come from a leadership that has consistently threatened the existence of Kurds in Southeastern Turkey and Syria.

Indeed, the Kurds have held the same scapegoat status as Uighurs in China: both groups were labelled as unwanted ethnic minorities and as "terrorists" by the states they inhabit. Let's not forget the military coup of 1980, when the Kurdish language was officially barred from private and public life, the subsequent chipping away at Kurdish rights and the ever-looming threat to Kurdish safety at the hands of Turkish forces.

Let's not forget that while Turkey shames China for imprisoning their beloved Turkic singers with Uighur ancestry, Kurds were often imprisoned when caught publishing or singing in Kurdish languages.

Herein lies the ineptness of political response to the Uighur crisis: every country that either defended or maligned China's governance of Xinjiang has been seduced by both its global economic pull and the dulling awareness of their own hypocrisies and human rights abuses.

|

|

4. A history lesson

Despite the trade war with the United States and human rights concerns over Hong Kong, China has joined the West's global "war on terror," using it as the main motivation for Uighur detention.

It's difficult to pinpoint the strange, inverted logic of the American right urging China to terminate Uighur detention camps, and the irony of someone like US Secretary of State Mike Pompeo – a man who defends Western intervention in Muslim countries and American internment camps filled with Central American migrants – attempting to take the lead in reprimanding China.

Nothing good will ever come from detaining a specific ethnic group or minority. We can't help but think of how the war on terror affected millions of Muslims worldwide, but also the tragedies in Bosnia, Palestine, or Kashmir; the Rohingya of Myanmar.

The UN session that took place in July befell the eve of the 24th anniversary of the Srebrenica massacre of 1995, when over 8,000 Bosniaks were murdered during the last year of the Bosnian War and genocide. If that doesn't paint a clear enough picture of what's at stake here, then what does?

Here's what's at stake: deep-rooted generational trauma for members of the Uighur diaspora that – in the eyes of the Chinese government – will exhaust an entire ethnic group into submission.

The internment and torture of Uighurs isn't just about cultural oppression, but the psychological marginality of self. When the visual markers of shared identity are destroyed, the community is at stake; when the daily customs of the home are annihilated, families suffer; but when a language or celebration or religious custom is compromised, an entire community is at risk of an ethnic cleansing – from the inside-out.

Hind Berji is a freelance writer with experience in arts reviews and sociopolitical criticism.

Follow her on Twitter: @HindBerji

![Palestinians mourned the victims of an Israeli strike on Deir al-Balah [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2024-11/GettyImages-2182362043.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=xSHZFbmc)

![The law could be enforced against teachers without prior notice [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2178740715.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=hnqrCS4x)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News