Syria intervention deepens the UK's political divide

May broke with convention and committed British forces to military action without parliamentary approval and despite public opposition to UK intervention.

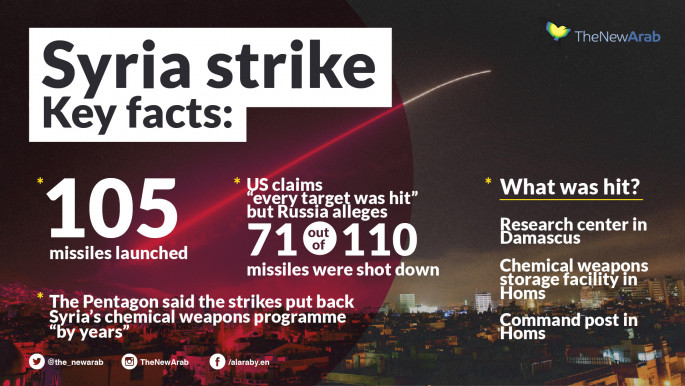

Four UK Tornado fighter jets fired cruise missiles at a site in Homs province where chemical stockpiles are thought to have been stored, with a research base in Damascus also targeted by the coalition.

No casualties were reported by Damascus and the three sites that were destroyed in the French-UK-US action were all thought to be linked to the regime's chemical weapons programme.

Parliament

It is the first time the UK has directly intervened against the Syrian regime and follows a chemical attack last Saturday - thought to have used chlorine and a nerve agent - on an opposition town, which left at least 40 civilians dead.

The government published the legal case for intervention on Saturday.

Legal advice presented to the government by Attorney General Jeremy Wright argued that the Syrian regime had repeatedly used chemical weapons during the seven-year war and were highly likely to deploy them again.

He also argued the strikes meet international law standards for intervention as there was "no practical alternative" and the action was "the minimum judged necessary for that purpose".

Chemical weapons have killed hundreds of people in Syria's war.

Restrictions on access to sites due to security factors and tight controls by the Bashar al-Assad's regime mean we do not know how many chemical attacks have taken place in Syria during the seven-year war and by whom.

Human rights groups believe scores of chemical attacks have taken place, including the use of chlorine and the much more deadly sarin. Almost all have targeted opposition towns and cities.

The Syrian regime is believed to be responsible for all, or the vast majority, of these attacks.

The most deadly include the use of sarin, which have been linked to the regime. In 2013, opposition towns in Eastern Ghouta were hit with chemical weapons, killing hundreds of civilians.

|

The collective action sends a clear message that the international community will not stand by and tolerate the use of chemical weapons. - UK legal report authorising strikes |

|

The village of Khan Sheikhoun in opposition Idlib province was targeted with the nerve agent in 2017, killing around a hundred civilians. Last Saturday's attack on Douma is thought to have used chlorine and a nerve age killing at least 40 civilians and forcing rebel group Jaish al-Islam to surrender the town to the regime.

Red line

With such proliferation in these attacks, May argued that Britain could not allow the use of chemical weapons to be normalised "either within Syria, or on the streets of the UK or elsewhere".

"The collective action sends a clear message that the international community will not stand by and tolerate the use of chemical weapons."

May said she will speak to parliament after it re-convenes from its spring break about the military action and that she was "confident" that the strikes were successful. She also argued that speed was of the essence and intervention could not wait.

|

| [click to enlarge] |

Her opponents have argued that she didn't re-call parliament for a vote on military action because she believed she would lose.

The UK does not have to legally consult parliament on military intervention, but the 2003 invasion of Iraq - which involved British forces - led to a precedent of votes on major military action.

In 2013, the Conservative government lost a vote on launching strikes on Syria following the Eastern Ghouta attack.

Division

Many analysts have argued that this gave the Syrian regime a green light to continue its use of chemical weapons - when the US also backed down on military intervention - and May was correct to override parliament and launch strikes on Saturday.

The military pressure on the Syrian regime in 2013 did lead to Damascus to officially "hand over" its chemical weapons' stockpiles. The mechanisms in place for this were not viewed stringent enough to ensure all these deadly weapons had been surrendered with inspectors relying on the blind trust of the regime.

UK opposition leader Jeremy Corbyn has opposed all military intervention in Syria. After Saturday's strikes he called for a "war powers act" that would commit governments to getting parliamentary backing prior to military intervention.

"What we need in this country is something more robust, like a war powers act, so that governments do get held to account by parliament for what they do in our name," he said.

Pressed on Sunday morning by Andrew Marr on the BBC about whether he would ever back military intervention in Syria, Corbyn refused to give a clear answer.

Instead he has called for independent investigations into future chemical weapons attacks, despite ignoring an earlier investigation that judged the Syrian regime was almost certainly responsible for the 2013 and 2017 sarin attacks.

He said given evidence the regime was responsible for chemical attacks he would "present this" to the Assad regime, but did not give any examples of how he would deter their future use.

Saturday's military intervention has not only split the UK's biggest parties - the Conservatives and Labour - but also led to many in among May and Corbyn's own ranks from disagreeing with the decisions taken by their leaders.

Some Tories have said that May should have consulted parliament before military action was taken. Others in the Labour Party have criticised Corbyn for being too soft on Assad and offering no coherent alternative to military intervention.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News