Unfulfilled donor promises leave Syrian refugees vulnerable

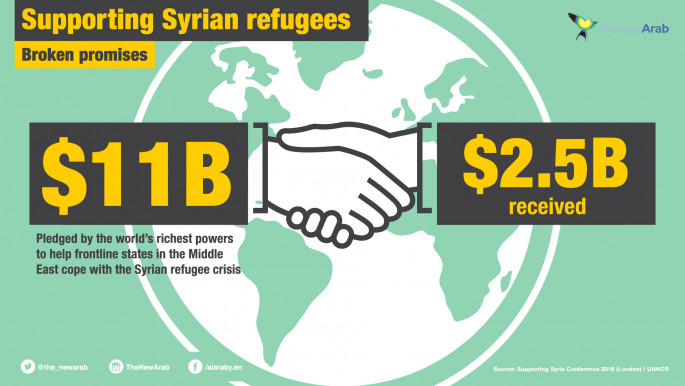

But four months later, less than a quarter of the headline sum has been handed over, and five million people are still at risk in an unstable region.

Countries such as Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey are struggling with the influx - and the displaced populations face the threat of radicalisation in their ranks.

"So I think there's a collective failure that will have to be addressed," said Amin Awad, the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees director for the Middle East and North Africa.

Awad said that, since February, when foreign ministers from around the world gathered at a London donor conference, only $2.5 billion has actually been disbursed.

Frontline states

This sum has come in the form of loans, grants for specific uses like student bursaries, and straight-forward humanitarian aid - but it has not proved enough.

"I think the frontline states are disappointed and they feel they're left alone," he said in Washington, where he is meeting US officials and experts.

Quite simply, the world is facing an unprecedented refugee crisis with at least a dozen protracted wars and crises ongoing at the same time.

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

There are more refugees worldwide than ever before - around 60 million - and more than a third of these are from the broader Middle East region alone.

"If you look at the Middle East population compared with the world's seven billion people, it is about five to seven percent," he said.

"And yet they've produced 35 to 40 percent of these cases," he added. "It's a region that has seen a lot."

Iraq has been evolving through periods of instability and of outright civil war since the US-led invasion of 2003 ousted long-standing dictator Saddam Hussein.

Syria was plunged into chaos five years ago when Bashar al-Assad moved to crush anti-government protests, while Yemen and Libya remain in the grip of civil conflict.

Last year, Europe faced what Awad called a "great march" of up to a million refugees who crossed the Aegean on rafts and walked north through the Balkans.

As that route has since become closed off, refugees are turning again to boats to take them from the North African coast to Italy - often with tragic consequences.

Ban on Muslims

The purpose of conferences like the one in London is to internationalise the issue, as frontline Middle East states face the greatest burden.

But - despite a generous attempt by Germany to resettle many thousands of refugees - if anything the mood has moved further from collective action.

In the United States, White House challenger Donald Trump has damned Syrians as potential terrorists and proposed banning all Muslim immigration.

In Britain, supporters of a vote to leave the European Union have stirred fears of boatloads of economic migrants arriving to feast off the welfare state.

|

The purpose of conferences like the one in London was to internationalise the issue, as frontline Middle East states were facing the worst burden. But if anything the mood has moved further from collective action. |  |

And in continental Europe, reports of mass sexual assaults by migrant gangs have fed the rise of populist parties and angry anti-immigrant rallies.

Awad does not want to see the UN refugee agency dragged into any national debate, but he is very clear about what is at risk if pledges are not met.

"There is a difference between a refugee and a migrant, and here I must stress this very loudly; words matter," he said.

"A migrant is a person who is moving due to economic reasons... A refugee is a refugee who is fleeing conflict or persecution."

States are bound by international humanitarian law and practive to accept refugees and to treat even unqualified economic migrants with humane dignity.

Radicalisation risk

But if this pact breaks down, it is not merely a moral stain: governments have hard-nosed, self-interested security reasons to head off the refugee crisis.

"We have to look at the security issues that we're looking at globally now," Awad said.

"We have to look at radicalisation, we have to look at the massive movement of people, and we have to look at the despair that those refugees face."

Would it be legal to refuse to accept Muslim refugees?

"No. The international instruments we have basically say you can not discriminate against anybody."

And is there any hope in sight?

"It depends on the leaders of our generation - the political leaders."

![London donor conference [AFP] London donor conference [AFP]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_345x195/public/media/images/891A109E-70E2-424E-AF94-672C091299AD.jpg?h=d1cb525d&itok=73uAeKDY)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News