Travelling back in time through Reem Bassiouney's Al Halwani: The Fatimid Trilogy

What can fiction teach us about the world we live in? According to Egyptian novelist Reem Bassiouney, it can impart lessons on everything from the history of the lands in which we live to secrets about how to communicate and love.

Bassiouney is likely a little-known name in many English-speaking countries, but her work is widely read across the Arab world. She studied at Oxford University and has worked in the UK and the US, as well as in Egypt.

Her fiction has garnered awards, including the 2020 Naguib Mahfouz Medal for Sons of the People: The Mamluk Trilogy; the same book was also nominated for the Dublin Literary Award and is currently being adapted into a TV drama.

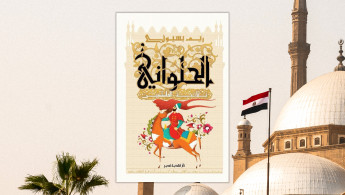

Like The Mamluk Trilogy, Bassiouney’s Al Halwani: The Fatimid Trilogy – for which she has just been awarded the 2024 Sheikh Zayed Book Award for Literature – is a historical novel.

It is also, in some ways, the story of Egypt, although none of its protagonists are Egyptian: Jawhar Al-Sakelli is Sicilian, Badr Al-Gammali is Armenian, and Youssef Ibn Ayoub is a Kurd. And yet these men – all real historical figures – are partly responsible for helping to build Egypt.

“I have had a kind of mission from writing my historical novels from the very beginning because most of my historical novels are written about foreigners or people who are not originally from Egypt, but they contribute to Egypt and live there,” said Bassiouney.

“And I think that the strength of Egypt was in embracing people, giving them a chance to prosper, to build, to make a difference.

“I was trying to convey that humans make history, not just people coming from a specific country. [It’s about] how these people influenced Egypt, and became part of Egypt. They were buried in Egypt. They built Egypt,” added Bassiouney.

Navigating global identity

Bassiouney’s novel addresses questions and debates about identity that abound globally.

“Unfortunately, when speaking about migration worldwide, there is this notion of ‘let's look for the real Germans, the real Egyptians’,” commented Bassiouney.

Bassiouney added, “They are as real as others because they decided to make this their home. It's not just where you are born, but where you decide to make your home.”

The subtleties and nuances of the discussion around immigration and home are matched by the subtlety and nuances in Bassiouney’s writing.

Bassiouney is currently a lecturer and head of the linguistics department at the American University of Cairo. Although all but one of her academic books have been written in English, she found that only Arabic allowed her to express what she wanted when it comes to fiction.

“I attempted to write fiction in English, and I couldn't express my feelings,” she said.

“I did not feel like I had the freedom to write what I wanted. One of the things is that in Arabic, tense is not very clear. So, in Arabic, I can speak about the past using the future, or I can speak about the past using the present.

“But in English, tense is very clear. So, I think I made many grammatical mistakes when writing in English.

"If you're writing academically, everything is in the present tense anyway, but once you start narrating a story and you want to go back and forth, Arabic liberates you because there is no restriction on tense.

“And this is a linguistic point that I think only a linguist would be able to compare both languages in this way,” Bassiouney elaborated.

Expanding access to Arabic literature

Although some of Bassiouney’s works are available in English, her winning book is yet to be released for English-language readers (it is forthcoming in a translation by Roger Allen and published by Dar Arab).

She is far from the only Arabic writer with few English translations of their work. According to research presented at the Frankfurt Book Fair and published by Literature Across Frontiers, only 596 works of Arabic literature were translated and published in the UK and Ireland between 2010 and 2019.

Although this is nearly double the number published in the previous decade, it remains a small amount considering the tens of thousands of new fiction books published in the UK each year.

Bassiouney is clear about the benefits of translating works from around the world: “Having historical novels, having novels in general, translated into English will give us a broader view of culture, of people. The most important message is that it will tell us that we’re not that different. We have the same feelings, and we may have different ideas about things, but that does not necessarily have to hinder us from communicating.”

Her words seem even more moving as we face the loss of many stories and storytellers in Palestine: at least 15 libraries have been destroyed in Gaza since October, according to Librarians and Archivists with Palestine, and dozens of writers have been killed.

But it’s not just the loss of professional authors and writers that is damaging; it is also the loss of everyday people and their unique stories.

Bassiouney says “If you lose a building and you lose people, you’re losing history, you’re losing a legacy.”

She adds, “That’s why I was thinking that we have to look at people as a rich resource for us, even if they don’t belong to our culture. All humans are rich resources, and all humans have their stories that could help us understand ourselves better. So we are all somehow connected, and once we understand this, we realise that, as John Donne says, if anyone dies, part of me is dying as well.”

Connection, for Bassiouney, spans a range of stories and writing: her favourite writers include the revered Egyptian novelist Naguib Mahfouz, who was the focus personality at this year’s Abu Dhabi International Book Fair, as well as classic British writers Jane Austen and Emily Bronte.

Bassiouney says she loves the “human aspect” and the love of novels like Wuthering Heights and Pride and Prejudice. Love is at the centre of all of Bassiouney’s stories, with all her books containing “love stories, passionate love stories.”

“And this is not fashionable,” she says.

“It's not fashionable in the Arab world, and it's not fashionable outside the Arab world. I think love is an essential part of our life, something that is never unfashionable. Love stories do not have to end happily, but in themselves, they are worth it because it’s in moments of love that bring humans together.

“And it's moments of love that suddenly you would relate to people that are totally alien to you by just realising how much they suffered in their love story. So, I think that personally having a love story is something very important in any work.”

The role of women in historical narratives

In The Fatimid Trilogy, and her other books, those love stories often rely on Bassiouney creating compelling women who stand on their own as well as in relation to any partners. To do this, Bassiouney focuses on the roles women have played in history.

“I think women in all my historical novels play a very important role,” she says.

Elaborating further, Bassiouney says, “I think that women have not been spoken about as much in history, especially women in the Islamic world. And they were marginalised in history and writing about them.

“But when I searched, I found out that, in fact, the role that women played historically is so strong and so dominant that it really needs to be written about. So, for example, during the Fatimid period, when there was chaos because of a specific caliph, his sister killed him because she decided that it was either the country going into ruins or he died, and she decided that her brother was going to die.

“So, this is one example, but there are lots of other examples of women saving the day, of women putting up with challenges, putting up with wars, being able to survive at very, very difficult times.”

Whatever the subjects of her books, whatever period they are set in, or whoever they take inspiration from, Bassiouney hopes her novels have universal appeal because she says: “My writing is not just about Egyptians or Arabs; it's about humans."

Sarah Shaffi is a freelance literary journalist and editor. She writes about books for Stylist Magazine online and is the books editor at Phoenix Magazine

Follow her here: @sarahshaffi

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News