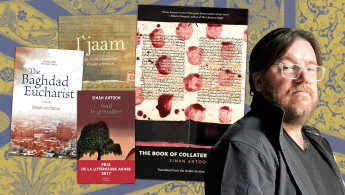

Echoing Palestinian perseverance: Iraqi novelist Sinan Antoon on NYU Gaza protests arrest and upcoming translation of Palestinian story

The world of academia is often viewed as a protected, perhaps even cosseted space, an ivory tower where professors squirrel away in their offices doing research, hushed hallways echo the footsteps of eager students, and the untidiness of the real world rarely encroaches.

But Sinan Antoon, an associate professor at New York University who was arrested for protecting students at a Palestine encampment, knows differently.

“Universities are not detached from society,” he tells The New Arab.

“The ideas in universities travel to the media, [people] write op-eds and they shape opinions and so forth. And the students who come to the universities are going to go out to society to either try to change it or reproduce the same injustices.”

Students protesting the war on Palestine haven’t waited until leaving university to try and change society; encampments have gone up at educational establishments around the world, where students have camped out to demand their colleges divest from Israel, call for a ceasefire and protect free expression, among other things.

This movement has shown that students are no longer willing to stay silent in the face of injustices, and neither are their professors, like Antoon.

One of those encampments was at Antoon’s own university, where students set up in Gould Plaza, near the university in Greenwich Village.

When the NYPD was called in to break the encampment up on April 23, Antoon was among staff members who formed a human chain to try and protect students.

“We heard that the police were amassing around it [the encampment] and were going to attack,” says Antoon.

“So we made a shield around the students and then we were arrested by the police. It's the first time in the history of New York University that police are called on campus to arrest. And so we are arrested for simply defending our students.

“There is a longstanding history now [of] the complicity and interconnectedness of higher education and global capital and police departments.

"Also, we live in New York City where the NYPD has an office in Tel Aviv and gets trained by the IDF. And the NYPD has a long history of racism towards black and brown people and spying on Muslims and so on.”

Injustice at the hands of American institutions — not the first time

Antoon was arrested for four hours before being released; no charges were brought against him, thanks, he says, to continuing protests and demonstrations by the students.

But the anger in Antoon’s voice, when he talks about the university’s actions, is clear: “There has never been an apology from the president of the university or any acknowledgement of how horrendous this was, but there were votes of no confidence from different departments and different people and lots of letters of condemnation.”

Antoon well knows injustice at the hands of American institutions; as an Iraqi, he has twice seen his country invaded by US forces.

The first time, he was a teenager, hiding in the darkness of a shelter with a transistor radio, the second time, in 2003, he was living in Cairo, Egypt.

Antoon's literary journey

As a writer and a poet, Antoon has often processed his experiences through his work, and as an Iraqi poetry is in his blood.

“Baghdad, the city I grew up in, was the capital of an empire,” he says. “It was, in pre-modern times, the cultural centre. In a way, we're all programmed because poetry is part of the cultural tradition, but for me, it's another language to describe the world and to read the world.”

Anton reads the world in Arabic and English, and as a translator of poetry and fiction helps others to read the world better.

Soon, UK readers will be able to read Anton’s translation of The Book of Disappearance by Ibtisam Azem, a Palestinian novelist, short story writer, and journalist based in New York. The translation has already been released in the US.

Born and raised in Taybeh, near Jaffa, the city from which her mother and maternal grandparents were internally displaced in 1948, she lived in Jerusalem before moving to Germany and later to the US.

The Book of Disappearance, out August 1 from And Other Stories, poses a question that is both simple and complicated: what would happen if all Palestinians simply disappeared from their homeland overnight?

The novel is told mainly through the eyes of Ariel and Alaa; the former describes himself as a liberal Zionist, faithful to the project of Israel yet critical of the military occupation of Gaza and the West, while the latter is haunted by his grandmother’s memories of being displaced from Jaffa and becoming a refugee in her own homeland.

As the novel progresses, and weaves in the voices of other characters, from restaurant patrons to a prostitute, The Book of Disappearance asks questions about belonging, history, memory and complicity, and with clear eyes presents the the ways in which Israel is a settler colonialist project.

“I have a soft spot for novels that can capture and crystallise an entire historic situation or the plight of the people, but also ones that are successful in dealing with the complexity of a certain situation,” says Antoon, who is Azem’s partner.

The Book of Disappearance originally came out in Arabic in 2014, and Antoon says the reaction by Palestinians shows the novel’s power: “The responses in Arabic and the responses from everyone, but particularly from Palestinians, whether in refugee camps or whether Palestinians living inside Israel, [was that] this book really spoke to them.

“Because it told their story. I mean, that sounds like it is very simple, but it's the truth. They could see themselves in the novel.”

It can feel simplistic to say that novels can help us empathise or sympathise, that they can foster a deeper understanding of a people’s plight, but within that triteness, there is a truth.

The Book of Disappearance, despite being written more than 10 years ago, speaks so clearly to the current war on Palestine.

In particular, it captures the dissonance many feel between what we’re seeing and hearing on our screens and from Palestinian people, and the so-called “official” versions of incidents from the Israeli governments or their supporters in governments including the US and UK.

Among the many examples of official memory trying to overwrite personal experience is the killing of Hind Rajab, the six-year-old girl shot at 355 times; despite reports into what happened, the US has insisted it is waiting for Israel’s version of the story.

Memories of Palestine's Jaffa

Antoon was drawn to translating the novel precisely because of the way it dealt with memory.

“I had been someone who had been reading and translating Palestinian poetry for a very long time, but the one thing that fascinates me and that I work on in other contexts, and why I wanted to translate the novel, is how it deals with memory and how there is this confrontation between oral memory and the memory of the colonised when it tries to reclaim its story.

“These, as opposed to the official memory of the colonisers, which is all about erasure and silencing and muffling, the voices changing the names and the landscape and Palestinians, you never existed.”

In the novel, Alaa recounts his grandmother’s memories of Jaffa, which are often dismissed by Ariel, who is exasperated at his friend’s constant examination of the past.

Of course, for Alaa (and other Palestinians), the past still exists in the present; changed street names, among other things, constantly remind Alaa of how Palestinians are viewed by Israel, the history that has been paved over, and the lives that have been destroyed and continue to be affected.

There is some comfort to be found in The Book of Disappearance in its descriptions of what is happening in Palestine and what has been happening since 1948, in a world where many have tried to make October 7, 2023, the start date for a conflict.

It once again shows the power of literature to clarify thoughts, ideas and arguments.

Although The Book of Disappearance is just one of a small number of works translated from Arabic, it has become part of a growing and newly forming canon that has been accessed by readers worldwide in the past nine months.

Palestinian creatives gaining more ground

Where a year ago only a few in the West would have been able to name a Palestinian writer (and if they could, it would likely be poet Mahmoud Darwish, whose work Antoon has also translated), now Palestinian creatives are gaining more ground, from musicians Nemahsis and Saint Levant to, perhaps most famously, the late academic and poet Refaat Alareer, whose poem If I Must Die went viral after he was killed in December in an IDF strike.

“If I Must Die is the perfect example because it compresses history and knowledge and feelings and trauma and hope all into just a few lines,” says Antoon.

Hope is crucial, and is to be found in The Book of Disappearance, echoing the way it is to be found in the stories of real Palestinians who persevere and survive and tell their stories.

“Raymond Williams, the great theorist, says that the intellectual is supposed to find the resources of hope,” says Antoon.

“There is a lot of hope in Ibtisam’s novel. Alaa reconnects with his grandmother and tells her story and tells Ariel that we will not forget the names, even if you change the street names.

"We are here. We were here. And we will stay here."

Sarah Shaffi is a freelance literary journalist and editor. She writes about books for Stylist Magazine online and is the books editor at Phoenix Magazine

Follow her here: @sarahshaffi

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News