Portrait of the Palestinian revolutionary as a Shakespearean character

I have wanted to interview Palestinian filmmaker, poet and translator Hind Shoufani for some time. We never met in person, but we are "virtual friends" and navigate intersecting circles of friends in Amman, Beirut and Dubai.

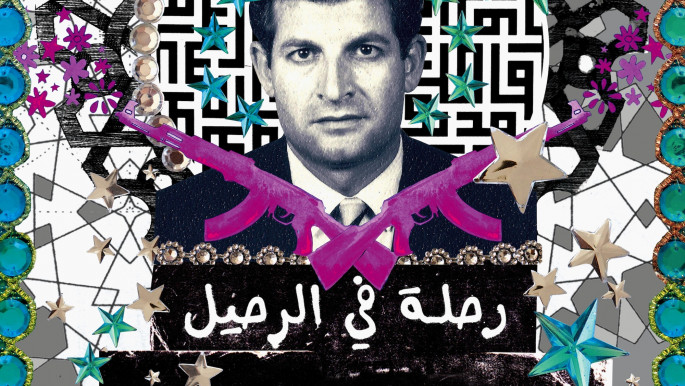

Hind is very busy these days. Her 2015 film, Trip Along the Exodus, edited by Ayman Nahle, is being screened across multiple continents this summer, but she graced me with some of her time between packing and fighting with airlines.

I had never before actually seen any of her films, so I did not know what to expect when I watched her most recent work.

The only time I could watch the two-hour feature was on the bus between Tripoli and Beirut, a few hours before the Skype call we scheduled. The film opens with Betamax footage of Palestinian propaganda, followed by scenes all too familiar to Arabs, those of the Arab Spring.

In the background, Hind is chatting with her father, Elias Shoufani, via telephone. He is in Damascus and it is still the early stages of the Syrian civil war.

Things are already grim in Syria. There are power cuts, and no food. Elias lives alone and the cleaning lady hasn't shown up. Explosions are drawing closer to his home but he doesn't want to move out. He is worried about his plants.

But it is the previous generation's catastrophe, the Nakba, whose 68th anniversary fell on May 15 - and not our generation's catastrophe, the Arab Spring, that is the starting point and the heart of the film's setting.

|

The Nakba marks the violent creation of the state of Israel atop the ruins of the Palestinian homeland, and the ensuing ethnic cleansing of much of the native population of Palestine in 1948 |  |

The Nakba marks the violent creation of the state of Israel atop the ruins of the Palestinian homeland, and the ensuing ethnic cleansing of much of the native population of Palestine in 1948. Since then, the story of the Palestinian people is the story of a refugee people in exile, a people in a perpetual state of resistance until their right of return to their homeland is fulfilled.

But apart from being a call for action and a raison d'etre, the Nakba is also the Palestinian's "original sin and curse", Hind agrees. Far from the romantic ideal of heroic revolutionaries, her father Elias, the main protagonist of the film, so to speak, comes across as so absorbed in the cause and its difficult politics that he leaves a trail of broken hearts in his wake.

It is a difficult film to watch for a Lebanese - let alone a Palestinian - who was born into the darkest days of the Palestinian cause in the latter decades of the 20th century.

But as a young Arab, this also meant I was less familiar with men like Elias Shoufani, despite him being a giant of the Palestinian revolution.

With Shoufani's testimony of exodus in the film, his separation from his family that he would not see again for decades - and then only at his wife and Hind's mother's funeral - and his great sacrifices of love and personal success in the cause, a viewer well-connected to the Palestinian plight can't help but get emotional.

I become tearful on the bus, as the Nakba's toll unfolds - told through intimate father-and-daughter encounters, all against a backdrop of ongoing suffering, new Nakbas, and melting homelands in the present day.

|

The Arab audiences are heavily invested in the political side of the story, especially with regard to Elias' clash with late Palestinian leader Arafat |  |

Trigger warnings

This is the starting point for my conversation with Hind, to whom I jokingly suggest including "trigger warnings" in the film's presentation. Elias' melancholic tone throughout the film had sparked something in me, I who had thought I had already been jaded beyond the capacity for outrage.

|

| A dreamy scene showing Hind's mother, Yasmine [HS] |

"When you're filming and interviewing your father, it's very hard to figure out objectively how his face is performing. He's not an actor, and I'm so accustomed to my father that I don't receive input and stimuli from his face as other people do," Hind tells The New Arab.

"The reactions to the film vary from country to country," said Hind, based on people's emotional expressiveness. Arab audiences are heavily invested in the political side of the story, especially with regard to Elias' clash with late Palestinian leader Arafat, she told me.

Still, Arabs in places like Tunisia, relatively removed from the conflict in Palestine, Hind says, were very emotive and would hug her and cry after the screenings. In Japan, former Japanese Red Army members who knew her father well would also "silently" express their sadness.

By contrast, non-Arab audiences, from Europe to Japan, unfamiliar with Elias' role in Fatah al-Intifada were mostly invested in the notion of a man "who was in a good position in life and was charming and attractive, giving up everything for his cause, losing his wife and eventually his entire family", Hind explained.

|

One theme throughout the poems Hind reads between different segments of film is the burdensome relationship with Palestine |  |

Generational fatigue

Our conversation jumped from the start of the film to the very end. In the epilogue, Hind reads a poem declaring the Palestinian revolution failed. With the Oslo Accords coming to a sorry end and armed resistance confined to Gaza, and even there mostly in a defensive posture, and with the Palestinian diaspora largely ignored by all key political players, it is not as cynical a judgment as it may first sound.

|

| Elias Shoufani in one scene [HS] |

One theme throughout the poems Hind reads between different segments of film is the burdensome relationship with Palestine. While the film is far from being A Trial of Elias Shoufani, there is clear tension between her narrative and his, not least because he chose to put "the cause" ahead of the family.

In the film, described by Electronic Intifada as "an ode to an absent father", Elias is seen as a man who never lost his belief that victory against Zionism, with which he is adamant there can be no compromise, is inevitable.

He is bitter, and he renounces both sides of the Palestinian schism as either charlatans or misguided Islamists, but he was still writing books and articles to educate the future generations he is certain will lead the liberation of Palestine.

But Hind does not have that kind of resolute certainty. Can we generalise to say her sentiments echo those of the Palestinian millennials, who are open to outcomes other than the full right of return, the full liberation of Palestine, and the full repatriation of Israelis?

She is keen to tell me the angry, frustrated poems were influenced in part by the brutality of the war in Syria, which only worsened after filming was completed, as her footage was edited into shape. This is not to mention the impact of racism she suffered in the Levant as a Palestinian, especially when it came to paperwork and visas.

"I'm definitely angry, but I don't necessarily have less hope than he does," Hind says of her father. As a poet and filmmaker, she interacts with the notion of Palestine on a more emotional, spiritual and sensual level than her father's political, logical platform.

|

Elias Shoufani was born in a village, he lived in a warzone, and he experienced exile first-hand. His concerns were mainly about how to liberate Palestine |  |

But Hind does agree there are profound differences between young Palestinians and the Nakba generation. "Our generation is not classically educated as my father's was," Hind says.

He was born in a village, he lived in a warzone, and he experienced exile first-hand. His concerns were mainly about how to liberate Palestine.

By contrast, our generation, more entitled and more accustomed to the luxuries of life - internet access and home entertainment - have different frustrations and expectations:

"We are part of a consumerist, capitalist, individualistic experience that makes us much more selfish and privileged."

That said, both Hind and Elias are angry at the status quo, she tells me, albeit in different ways.

|

Elias' anger with an enemy so evil that it set out not just to uproot Palestinians but to efface their identity led him to become all-consumed in the cause, but that also meant he was not there for his family |  |

Unlike the works of fellow Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman, it is anger not absurdity that seems to be the dominant theme of her portrayal of the Palestinian cause.

|

Hind has not expressed her anger through politics; rather, she uses filmmaking, poem, colour, music - and glitter - to interact emotionally with the same cause.

Elias' anger with an enemy so evil that it set out not just to uproot Palestinians but to efface their identity led him to become all-consumed in the cause, but that also meant he was not there for his family.

His daughters grew away from him, his wife passed away during his long absence, and his brothers and sisters, a few kilometres away - but behind borders impossible to cross - are angry with him and his choices, which meant, for decades, they met only via telephone.

"It's a complete disaster," Hind tells me. "All the men who worked for the revolution, they got divorced, they didn't manage to take care of their children the way they were supposed to, and they didn't make a lot of money if they did not steal."

For some, including her father Elias, when the revolution ended "they found that they had spent twenty years of their lives with no business acumen of any sort. They did not have any career to fall back on".

|

Trip Along the Exodus explores the past 70 years of Palestinian politics seen through the prism of the life of the filmmaker’s father, Dr Elias Shoufani, a leader of the Palestine Liberation Organisation and an academic and leftist intellectual who was one of the leaders of the opposition to Arafat within Fatah for 20 years. Born in Maaliya in the Galilee and educated at the Hebrew University and Princeton, the multilingual and erudite Dr Shoufani was also the Arab world's leading analyst of Israeli affairs for more than a generation. |

This is the story of every Palestinian refugee exile who worked for his country, she adds, quoting her uncle Rami Khouri - but says she is, nevertheless, the daughter of privilege compared with others.

"I didn't lose family members to a bomb… I cannot judge anyone in the diaspora whether they did the right thing." In the end, Hind repeats, Palestinians were facing an enemy so well trained, educated and systematic that they barely had any chance, at least initially.

To be or not to be

Ultimately, Elias comes across in the film as somewhat Shakespearian.

Hind concludes our conversation with the revelation that her "dark, solemn, flawed" father's character was first sculpted by her aunt, a drama teacher.

"His was an extremely dramatic story. It fits all the dramatic requirements of an actual feature film. You have a character who is stubborn, bitter and dark."

|

|

She continues: "He is very flawed, in a Shakespearean way." Her father's persona was a prime motivation for making this film.

"You have this fantastic leader whose one fatal flaw brings him down. It is called a hamartia," she adds. This is a reference to a theme that figures highly in the tragedies of Hamlet and Julius Caesar; in this case it is the dogged pursuit of ideology and a cause, regardless of its merits or the sacrifices it entails.

A niche film

The film will be gracing the silver screen in several cities. In the Arab world, it has already done well at the box office in Dubai and Cairo, but elsewhere in the Levant, it has had to grapple with censorship issues and has only been screened privately.

In the US, Hind's film will be screened in select venues in New York and Boston. But on a wider scale, she says, there has been a thorough lack of interest stateside in Trip Along the Exodus - though she says it will soon be available to US audiences online.

"It's a niche film about something specific - the revolution against Yasser Arafat - that they don't get. They don't want it because it gives an impression of Palestinians that they don't want in the media," Hind proclaims.

"My father is not a terrorist. He is not in a camp. He is not a Muslim fundamentalist. He is not a downtrodden victim. He is proud and doesn't fit the profile they want of a Palestinian."

Catch an upcoming screening of Trip Along the Exodus at the Goethe Institute in Istanbul, Turkey, on May 29 and June 1, at Bozar in Brussels, also on May 29, or join in with a panel discussion on the film in Bilbao on May 31.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News