Lively colours and mural art cover the entire downtown area of Al-Qalamoun, a picturesque coastal village in northern Lebanon.

From the highway to the seaside, all buildings – including a historical communal bakery and ancient ottoman gates – are painted in bright blue, yellow or pink.

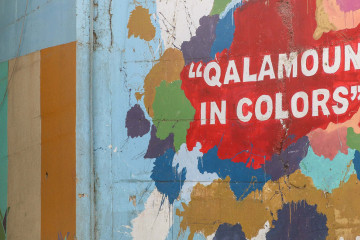

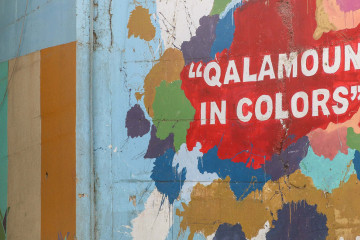

"Qalamoun in colors!" began in 2019 when Utopia, a Lebanese NGO (non-governmental organisation), decided to carry out an art project in this small town located 75 km north of Beirut. A hashtag was created, and the project attracted social media attention and tourism.

While murals and street art are popular among NGOs in Lebanon because of their low cost and high visibility, Qalamoun’s project trumps most others by its scope, covering 51 buildings.

"The NGO-isation of a whole country is problematic because short-term aid projects replace long-term public services. And international donors don’t give for free: they expect visibility"

"We thank the NGO, the result is beautiful. It has had a great impact on the youth," Rim Kaddour told The New Arab by phone. The young woman is one of the 120 people who painted the walls of their city, along with art students and a Palestinian artist.

Vivid on the outside, mouldy on the inside

But three years later, the structural problems reappeared: the houses were still dilapidated, the infrastructure was deteriorating and the roads, full of holes, were increasingly dangerous to drive on.

"We would have preferred to have interior renovations rather than exterior painting. It would have helped us more," Salma al Hendi, a Palestinian resident of Qalamoun, told The New Arab.

Together with her neighbours and relatives, she affirmed that the NGO did not ask them what they wanted. "We had to beg one of the workers to paint over a single inner wall of our house," Salma remembered, standing in her small apartment where mould covers the walls. "The water from our neighbours' sewers seeps onto them, it really stinks," she said.

“This situation affects us psychologically, we are as depressed from the inside as our houses,” Salma added. These problems should be taken care of by the state instead of NGOs, inhabitants said. "We want the municipality to intervene to maintain the roads and infrastructure," Rim Kaddour told The New Arab.

'A Republic of NGOs'

“Qalamoun in colors” is symptomatic of Lebanon’s decay. Its infrastructure is crumbling as the country enters the third year of the worst economic and social crisis in its history.

Not only has the Lira lost 90% of its value, but 82% of Lebanon’s inhabitants now live in multidimensional poverty. The public sector is reeling under the loss of civil servants, thousands of which leave their jobs because of low salaries.

In the meantime, NGOs garnered 1 billion of dollars from international donors in 2022 and continue to attract what is left of Lebanon’s youth with higher salaries. 5,000 NGOs provide essential healthcare, infrastructure, humanitarian relief and development projects to their “beneficiaries” where the state is absent.

In fact, Lebanon has become a “Republic of NGOs”, according to Clothilde Facon, a researcher in political sociology at Sorbonne Paris Nord University who studies the works of NGOs and the UNHCR in Lebanon.

The NGO-isation of a whole country is problematic because short-term aid projects replace long-term public services. And international donors don’t give for free: they expect visibility.

|

“This explains the popularity of street art and murals: they are good for marketing and showing presence, even though they barely actually change anything,” Clothilde told The New Arab.

Not only do they not change anything, but they reproduce a neocolonial logic, according to the researcher. "There is an imbalance of power, and it is Westerners who impose their vision and their solutions on the countries of the South," she says.

A call for justice

A few kilometres up north, the inhabitants of Bab al-Tebbaneh experience the bitter consequences of the state’s withdrawal every day.

In the most marginalised district of Tripoli, the poorest city in the Mediterranean basin, grey and dilapidated buildings are covered in bullet holes. Only a few stand out with vivid colours and monumental street art murals – inaugurated last October by a French NGO, Artivista.

Six French and Lebanese artists painted over five facades which the NGO renovated, also organising conferences about street art and corruption in schools, universities, and cafés. The goal was "to transmit street art as a means of expression to young people, and to bring joy to their hearts," Claire Prat-Marca, Artivista’s founder, told The New Arab.

Artivista’s 90,000-dollar project fully involved the neighbourhood residents and businesses, she said.

Yet, like in Qalamoun, inhabitants claim they have not been asked. "They repainted the facades facing outwards – people on the highway can admire the art, but not us," Sabah Ali Jawhar, a 60-year-old mother living in one of the buildings, told The New Arab. "We thank the NGO, it brings joy to our hearts, but installing solar panels or water tanks would have really changed our daily lives," Sabah said.

Mould covered the walls of her apartment, which was plunged into darkness because of a power cut. Since the crisis, the state has only provided two hours of electricity a day at most and running water has become a luxury.

In this district with a reputation for being a dangerous, violent area, plagued by delinquency, her first demand is for justice. “The state is absent, all the money goes to Beirut and we are left with nothing,” said the mother of two sons, one of which is imprisoned for five years without a ruling, like many of his neighbourhood.

Depoliticising Lebanon’s inequalities

Lebanon’s highly centralised form of government has left most regions marginalised, from the Bekaa Valley to Tripoli. At the end of the country’s civil war (1975-1990), reconstruction efforts channelled billions to real estate projects such as downtown Beirut’s Solidere scheme, while slashing social services and redistribution. Lebanon recently has been called a “tax haven”, while the richest 10% own as much as 70% of its population.

It is precisely these structural inequalities that NGOs are not helping to address. "Humanitarian and development aid does not change the system, but support it," Clothilde told The New Arab. "NGOs depoliticise what is happening in Lebanon. They simply approach the situation through a purely humanitarian lens," she criticised.

This, in turn, has disastrous consequences for Lebanese society. The country’s NGO-isation “diverts" young people who would have been involved in activism, radical politics or civil society organisations (CSOs) towards development aid. “This creates a divide between over-funded international NGOs and underfunded local CSOs, which lose funding as soon as they take a political stance.”

As a result, efforts to change Lebanon’s corrupt political system remain invisible and underfunded. Instead, Clothilde and other researchers called for supporting local, alternative, and politicised groups to restore Lebanon “from the bottom up” rather than repainting its facades.

Marine Caleb is a French freelance journalist living in Tripoli. Having lived for many years in Quebec, she runs the media professionals' magazine Le Trente, writes for various Canadian media, and specialises in migration and gender issues.

Follow her on Twitter: @MarineCaleb

Philippe Pernot is a French-German photojournalist also living in Tripoli. Having covered anarchist, environmentalist, and queer social movements in Germany, he is now the Lebanon correspondent for Frankfurter Rundschau and editor for the news website NOW Lebanon.

Follow him on Twitter: @PhilippePernot7

Additional reporting by Rayane Tawil

![The main street of al Qalamoun, lined with cafes and houses whose facades have been repainted by the NGO, Utopia. North Lebanon, 12 November 2022 [photo credit: Phillipe Pernot]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2022-12/Untitled_27.jpg?h=d1cb525d&itok=Np1lIUyi)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News