Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram to stay connected

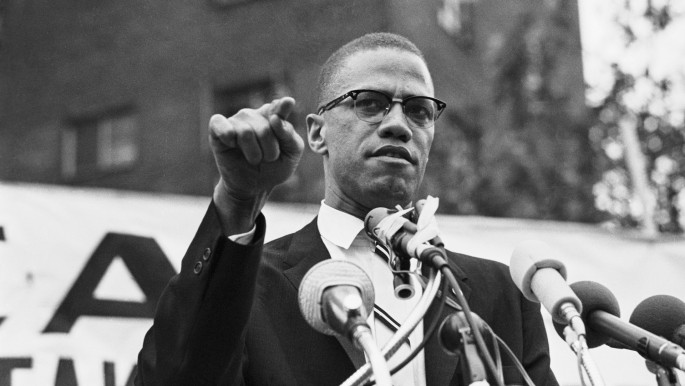

Malcolm X: Muslim and misunderstood, a pioneering force of the US civil rights movement

New evidence of a conspiracy by the New York Police Department (NYPD) and the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) conspiring to assassinate Malcolm in Harlem in 1965 has been revealed by lawyers.

Ray Wood was an undercover police officer at the time, and his family and attorney claim that Wood wrote a letter on his deathbed confessing that the NYPD and the FBI was a party to his murder, revealing that it was his job to make sure Malcolm’s security was arrested days before the assassination so that he did not have any protection at the Audubon Ballroom where he was killed.

As a result, a review was opened looking into his death, as well as the three Nation of Islam members who were convicted of his murder.

The pioneer

In his book, Martin & Malcolm & America, the late author James Cone summarised the roles of the two key civil rights activists in the fabric of America's rich historic tapestry, calling both Dr Martin Luther King and Malcolm X "revolutionaries" in their own right.

In common lexicon, the late King is presented as the perpetual advocate for nonviolent resistance and Malcolm X, the representative of angry, militant resistance in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s. The superficial dichotomy presented by history between the two Black civil rights activists followed both their memories, and it is woefully simplistic in its portrayal of Malcolm in particular, who was not violent, nor was he militant.

Malcolm believed that Black people in America had the right to defend themselves against the tyranny of US state violence and discrimination, both of which were lived realities for him and those like him. Nonviolent resistance, he believed, was futile in the face of violence, though in later years he would come ever closer to King's point of view, and vice versa.

"King was a political revolutionary," wrote Cone. "Malcolm was a cultural revolutionary. Malcolm changed how black people thought about themselves. Before Malcolm came along, we were all Negroes. After Malcolm, he helped us become black."

Malcolm X: Preacher, Muslim, Leader

|

| Dr Martin Luther King and Malcolm X, circa March 1964 |

Born to Baptist minister Reverend Earl Little, Malcolm grew up straddling religion and black identity in a country that, having outlawed the long and bloody practise of slavery, remained rooted in discrimination and racism.

Religion and politics would continue to represent an integral part of Malcolm's vision for Black liberation when he was a member of the Nation of Islam and later, a Sunni Muslim.

He was brought up in Lansing, Michigan, where the spectre of white nationalism was never far from his home. At one time the city had 1,000 registered members of the Ku Klux Klan.

When he was six years old his father died after being hit by a streetcar – a suspected murder by white nationalists – and not long after that his mother Louise Little was committed to a hospital, leaving him and his siblings to grow up in a mixture of care and foster homes.

Years later in prison where he was serving time for robbery from 1946 to 1952, he discovered and joined the Nation of Islam, a Black nationalist organisation.

In 1959 Malcolm and the Nation of Islam released a documentary called The Hate That Hate Produced and it catapulted him into New York’s Civil Rights scene. It wasn’t long before he was positioned as Dr Martin Luther King’s antagonist – the violence to Dr King’s peace, the 'wrong' to Dr King’s 'right'.

It was a position that Malcolm understood he inhabited, and he reached out to the pastor on several occasions to bring together the two factions which had been posited as opposing forces in the same struggle to end racism in the US. They were two sides of the same coin, and Malcolm knew it.

"For the Muslims, I'm too wordly," he was quoted as saying.

|

| Malcolm X always drew a crowd [Getty] |

"For other groups, I’m too religious. For militants, I’m too moderate, for moderates I’m too militant. I feel like I’m on a tightrope."

From NOI to Mecca

Malcolm’s politics was married to his faith in that they existed together in one body, but separately as two distinct parts of his identity.

Malcolm X left the Nation of Islam in 1964 after becoming disillusioned by its precepts and its leader Elijah Muhammad and following a trip to Mecca he embraced a new name to signify his move to Sunni Islam: El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz.

The 3 April 1964 was an important date in his ideological journey. He delivered his famous speech "The Ballot or the Bullet", emphasising the importance of the global Black freedom movement and the fight against global white supremacy.

"It doesn't mean that we're anti-white, but it does mean we're anti-exploitation, we're anti-degradation, we're anti-oppression. And if the white man doesn't want us to be anti-him, let him stop oppressing and exploiting and degrading us. Whether we are Christians or Muslims or nationalists or agnostics or atheists, we must first learn to forget our differences," he said at the time.

|

We’re Muslims and our religion is Islam, but we don't mix our religion with our politics and our economics and our social and civil activities - not any more |  |

"We keep our religion in our mosque. After our religious services are over, then as Muslims we become involved in political action, economic action and social and civic action."

"Ignorance of each other is what has made unity impossible in the past," Malcolm said in a later speech in August.

"We need enlightenment. We need more light about each other. Light creates understanding, understanding creates love, love creates patience, and patience creates unity. Once we have more light about each other, we will stop condemning each other and a United front will be brought about."

In the end, James Baldwin later said, by the time Malcolm and King died, "their positions had become virtually the same".

Narjas Zatat is a staff writer at The New Arab. Follow her on Twitter: @Narjas_Zatat

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News