No artistic discipline is more neglected in Islamic civilisation than its figurative art, which involves the depiction of humans and animals on any surface.

While the Jewish ban on this form of art has influenced the Islamic doctrines and cultures up till today; as Islamic civilisation grew in cultural centres outside the Arabian Peninsula, new Muslim nations continued making images in line with their inherited local artistic traditions, with varieties in terms of quality, quantity, styles, preservation conditions and the rules followed in determining what is permissible or not.

So, what is called "Islamic art" doesn't necessarily reflect religion or religious views but it surely reflects Muslim cultures that shaped the production of these arts.

"Unlike modern Muslim societies where heterosexuality is seen as the 'norm' by default, medieval Muslim societies considered bisexuality to be the norm for men, at least at the level of attraction and desires"

Yet, the topic that most modern Muslims wouldn't expect to find in the artwork of their ancestors is the depiction of love affairs and sexuality.

Although such depictions are rare if compared to the images done on other topics, the surviving erotic images are astonishing and mind-blowing.

Such works were painted for different reasons in books or on objects meant to be owned usually by educated and privileged individuals, as painting was – in general – a costly form of art.

In this article, we have a general view on the representation of gender and sexual diversity in classical Islamic art, providing a few examples from different eras and areas, and taking into consideration that the selected images are more conservative than the ones not shared.

Among the earliest surviving figurative arts in Islamic history are the wall paintings at Amra bathhouse in Jordan, which was owned by the Omayyad Caliph Alwalid bin Yazid during the 8th century.

Here we can see depictions of nude women bathing and topless dancers and men wrestling in underwear, but also there are heterosexual scenes of love and sex affairs.

During this period, most local artists were still influenced by Greco-Roman artistic traditions, belonging to a very sensual culture. Moreover, the historical reports show that Alwalid bin Yazid was a very secular libertine ruler, fond of visual arts.

This explains the existence of such images at his bathhouse. In fact, the tradition of decorating the walls of bathhouses continued to be widely spread around the Islamic world.

In his book The Ring of the Dove, the Andalusian polymath and jurist Imam Ibn Hazm al-Andalusi blames his friend for falling in love with an imaginary girl he saw in his dream, and he tells him: "I would excuse you if you fell in love with an image from those at the bathhouse." But what would be the images at the bathhouse?

Unfortunately, other than the Amra bathhouse, we do not have much bathhouse fresco remaining from the Islamic medieval period.

Yet, the use of the gender-neutral expression "loving images" is known in ancient Arabic literature to mean falling in love with male or female figures, whether depicted in paintings or as real human beings.

Unlike modern Muslim societies where heterosexuality is seen as the "norm" by default, medieval Muslim societies considered bisexuality to be the norm for men, at least at the level of attraction and desires.

Thus, the depiction of handsome youths would be equally beautiful and erotic as the depiction of girls, whether as wall paintings in the homoerotic bathhouse atmosphere, or anywhere else.

In fact, starting from the Safavid dynasty from least (1500 onwards), it is difficult to distinguish between young men and women in Persian art because beardless boys look soft and feminine, while girls are somehow masculine.

They both wear jewellery and a similar fashion style. Only the breast can be the key to distinguishing between the two genders, but even that feature is not obvious in many cases. This reflects not only the beauty standards at the time, but also the sexual preference in the Islamic world generally, and in the Persianate societies in specific.

This queer atmosphere can be extended to Turkish/Ottoman miniatures, where boys would replace women by cross-dressing while performing and dancing in public events. This was because it was not acceptable for women to 'humiliate their honour' in the presence of foreigners, while the sexual reputation of boys 'can be reconstructed' once they reach manhood.

In general, although Arabs were the most open nation in producing erotic literature in the medieval ages, their surviving figurative arts are more conservative than the works of non-Arab Muslims.

Nudity in Arab images was most of the time-limited and justified by context, while even intimate scenes were generally depicted in subtle ways. It seems Arabs believed that what is allowed to be spoken or written is not necessarily acceptable to be visually depicted.

This belief is persistent till today, and this view is extended to their conservative stand on the depiction of prophets, while non-Arab Muslims did not find any problem in any topic.

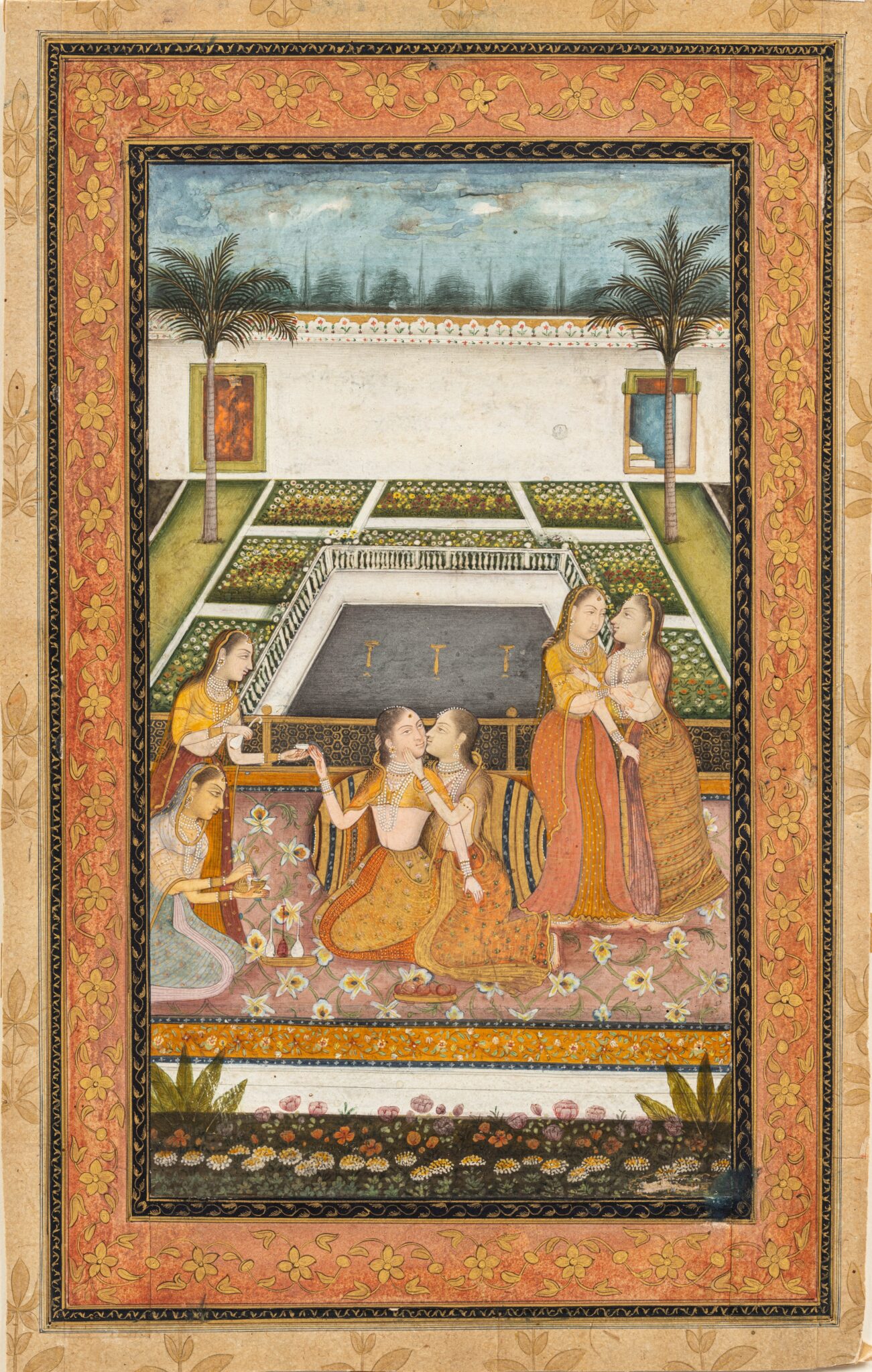

For example, Mughal art that flourished in South Asia under Islamic rule (1600 onwards) – can be considered the most erotic school among all Islamic art schools. This school was heavily influenced by a Hindu culture that is already filled with erotic sculptures and paintings.

Consequently, Mughal artists from all backgrounds saw no problem in depicting erotic scenes, including not only heterosexual couples but also other sexual forms and practices, including lesbian romance, orgies and even bestiality.

As Westernisation swept the Islamic world during colonisation in the first half of the 20th century, Muslims borrowed and adopted conservative sexual norms at the time, mixed with ignored religious views, which heavily influenced local arts and literature.

This led to the ban or censorship of some ancient works classified as violating public taste and resulted in the complete disappearance of homoeroticism in Islamic art.

Many modern Iranian artists are still inspired by ancient romantic Persian miniatures, but they avoid the depiction of nudity and handsome boys, in accordance with homophobic norms imposed by the modern regime and society.

Ironically, these norms do not look like the norms of ancient Muslim societies, but more like that of Victorian morality.

Jamal Bakeer is a content creator, author, audio-visual storyteller and expert in Arab/Islamic heritage and civilization.

Follow him on Twitter: @JamalBakeer

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News