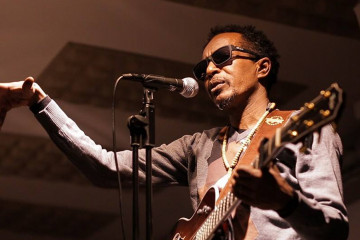

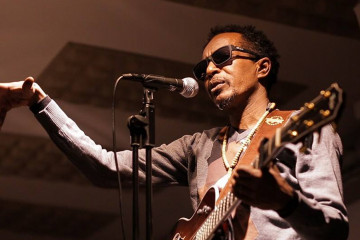

In 2008, Abazar Hamid had to hide 200 traditional jazz songs after his performances infuriated Sudan's then autocrat, Omar al-Bashir.

Now in exile in Norway, like many of Sudan's refugee musicians, he is squeezed between a relentless Covid-19 pandemic that has grounded live performances, and on-off coups back home in Khartoum that makes a return improbable.

“I was destroyed,” Abazar tells The New Arab of his feelings after the global outbreak of Covid -19. The pandemic swiftly buried his creative voice, and the one assertive component of his identity in exile: music.

"[Hamid's] conflicted emotions mirror that of Sudan's refugee musicians exiled in Europe and beyond: forgotten under the restrictions of the Covid-19 pandemic, frustrated by on-off coups back in their homeland"

“It was very hard to accept, live shows and contacts with audiences in Europe vanished. As a consolation, I've had more time to practice because more or less there is no chance to have a big band like before. To dodge the pandemic, I play solo now, the acoustic, and guitar. I'm trying to sing in English and in Norwegian to the available audience online.”

Annoying al-Bashir

Abazar Hamid, aka Tore Brun, who studied architecture but later dumped the profession after experiencing some initial musical success, angered Omar al-Bashir when the suspected war criminal was at the peak of his powers.

Abazar bravely started to work with traditional musicians in war-torn and the non-Arab Darfur region of Sudan in the early 2000s. This was a location where Bashir's army and the allied Janjaweed militias were reportedly carrying out a scorched earth campaign, leading to the widespread displacement of civilians.

“Sudan was headed towards the referendum of 2008 that ultimately halved the country into two. I saw a window to cultivate piece via music,” Abazar tells The New Arab.

With Bashir's secret police on his trail, Abazar fled first to Egypt where threats of kidnappings from the Sudan embassy also emerged. With his life on the line in 2010, Abazar and his family became the first guest musician to be ever granted protection residency in Norway. He has never returned to Sudan.

Reprieve

Like other exiled Sudan musicians dotted around Europe, Abazar fortunes had been brightening up. He was busy on the performing circuit, touring with his band, headlining orchestras, earning, and taking the fight to Sudan's Europe embassies in Berlin, or wherever venue he happened to tour with his band in Europe.

In April 2019, the tyrant Bashir was toppled in Khartoum. Abazar's dream of seeing Sudan, the beloved homeland he ran away from a decade earlier, appeared to become a reality suddenly.

“I was so happy. We had been waiting for a long time, finally. The people won and Bashir is in prison. The songs that were censored became revolutionary songs for people to sing,” says Abazar of 2019, the first phase of Sudan's historic revolution which has been since met on-off coups from the army generals.

Disaster

But on October 26, Sudan's pain deepened. The Sudan army general Abdel Fattah al-Burhan staged another audacious coup in Khartoum and placed the civilian prime minister Abdallah Hamdok under house arrest. The remnants of Bashir's army that Abazar fled from in 2008 is back in charge today.

“I'm in emotional turmoil again: Covid, exile, and on-off coups,” says Abazar of the recent month's events. “The revolution swept aside Bashir and the political wing of the Muslim Brotherhood but the military wing of the Muslim Brotherhood remains intact,” he tells The New Arab.

“So many people we were expecting this 2021 coup. That's why they started to resist it before it happened.”

"Though some political detainees have been released in Khartoum, Abazar says some of his music network in Sudan remain underground"

Before the latest upheaval of 2021, Abazar was planning a musical return to Sudan in 2022. Some of his songs were back on the radio, he says.

But because he is an anti-Sudan army musician, Abazar is not confident he will set foot in the homeland that he abandoned any time soon.

The general is isolated

Though he is far from home in exile, Abazar feels the first phase of the revolution genuinely changed the life of the ordinary fruit-seller in the streets of Khartoum.

“[The revolution changed] A lot. A very big change happened in my absence. People became more confident and people were optimistic, were working hard to establish the new Sudan. That was the big change,” he says.

With the Sudan army showing its authoritarian hand in on-off coups Abazar says his drumbeat won't freeze. “I'm thinking every day about Sudan. But I am also focused here to play my diaspora to support the Sudan ongoing revolution. I think this is very important.”

Though some political detainees have been released in Khartoum, Abazar says some of his music network in Sudan remain underground, now revolutionary musicians stringing beats in their aim to continue resisting the unrepentant army.

His conflicted emotions mirror that of Sudan's refugee musicians exiled in Europe and beyond: forgotten under the restrictions of the Covid-19 pandemic, frustrated by on-off coups back in their homeland. But he strongly feels the Sudanese people will win.

“The general is isolated.”

Ray Mwareya is the receiver of the 2016 UN Correspondents Association Media Prize and a regular freelancer for The New Arab. Ashley Simango, is a freelance journalist.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News