Beirut-based artist and writer Bassem Saad’s Congress of Idling Persons is certainly quite a unique example of filmmaking.

Recently premiered at the MoMA Doc Fortnight (23 February-10 March) and recipient of a Special Mention at CPH: DOX (23 March-3 April), Saad’s medium-length picture constitutes a performative act of political protest exploring the aesthetic boundaries between experimental cinema and video art.

"Lebanon’s local context serves as a starting point to explore other concurrent social tensions, including the late years of the Arab Spring, the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests, the war in Syria as well as the endless Israeli-Palestinian conflict"

The film features five main subjects – the helmer himself, DJ and translator Rayyan Abdel Khalek, musical artist Sandy Chamoun, writer Islam Khatib and activist Mekdes Yilma – who offer a series of (more or less) spontaneous reflections, anecdotes and scattered thoughts throughout.

Their words touch upon a variety of topics, and in particular, their own country’s long-lasting crisis, further exacerbated by the healthcare emergency and the tragic Beirut port explosion in 2020.

However, Lebanon’s local context serves as a starting point to explore other concurrent social tensions, including the late years of the Arab Spring, the murder of George Floyd and the subsequent Black Lives Matter protests, the war in Syria as well as the endless Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

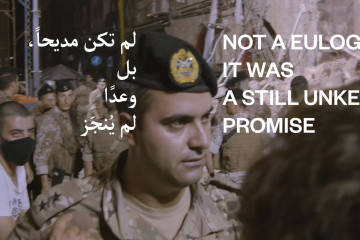

The subjects’ reflections are intertwined with extensive usage of archive footage, on-screen texts and a heavily manipulated soundscape (courtesy of Chamoun herself and Anthony Sahyoun).

The idea of distorting music and voices ultimately acts as a sort of metaphor embodying the audience’s overwhelming feeling of confusion, wherein the multitude of sonic sources prompts the cognitive overload we are exposed to on a daily basis.

It’s the disorienting, puzzling feeling we experience every day when we read multiple, contrasting news stories when we listen to the endless speechless analysts and political commentators providing us with their own indisputable truth, when we surf channels neurotically looking for something decent to watch, or when we witness an unstoppable flow of images depicting rage, violence and war.

The film opens with a static shot depicting a crowded Lebanese road, enriched by some tremendously timely words. Saad argues that “there is always anguish at the specific way in which the counter-revolution is enforced – by a military coup, overwhelming police repression, civil strife or genocide.”

In more banal instances, he adds, “the regime and the ruling class force the revolting population into a protracted war of attrition,” during which “there will be vengeful joy, guarded indifference, disenchantment and mass grief.”

Even though the opening scene and its on-screen text may reveal a first, intelligible topic to develop, such thematic clarity will not be kept throughout the picture.

At times, in fact, it may be hard for the viewers to fully grasp and contextualise the exact meanings of Saad’s on-screen text and the subjects’ speeches. Luckily enough, the key idea behind the making of the Congress of Idling Persons remains plain to see. The message is loud and clear: political battles are now needed more than ever – in Beirut, in Lebanon, across the Middle East, everywhere.

— The New Arab (@The_NewArab) February 25, 2022 |

Furthermore, the fragmented (and highly participatory) format chosen by the helmer allows him to steer clear of any rhetorical trappings and contributes to delivering a considerably sophisticated piece.

Through its cryptic language, Saad’s picture can open up multiple interpretations. In general terms, these readings may significantly vary depending on the venue chosen to watch this 36-minute piece (a museum? A theatre? A lecture hall?) as well as one’s geographical and ideological background.

The closure of Saad’s film culminates with the presence of a deafening, pounding score accompanied by several layers of sounds featuring recordings from riots and other chaotic events.

On the surface, the pattern is sung by Chamoun – an estranging song titled Dreams of the Imagination – may suggest that many of the things and feelings we may experience are just a product of our own brain (“Solitude is of the imagination,” “The fire is of the imagination,” “The sounds are of the imagination,” “The tears are of the imagination” and so on).

However, on a more abstract level, this aesthetic choice may be considered a way to suggest how our sensorial perception can be distorted while experiencing moments of hardship and living under a repressive regime, with no way out in sight.

Davide Abbatescianni is an Italian Film Critic and Journalist based in Cork, Ireland.

Follow him on Twitter: @dabbatescianni

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News