Christmas in diaspora: Reflections of an Iraqi priest

It is two days before Christmas, and Dako has a busy schedule of preparations.

In addition to overseeing the children's choir, a new addition to the community this year, recently Dako helped organise a bazaar with proceeds going towards Iraqi communities displaced by conflict in their homeland.

Last week, Dako also oversaw the organisation of a nativity play.

"It was maybe a bit long, 45 minutes, but a good occasion," says Dako, a stout moustachioed man in his mid-forties with an affable grin, an infectious laugh, and dark inquisitive eyes.

A mission away from home

Normally around 150 people attend Sunday services.

However, on Christmas day, explains Dako, as many as 500 congregants may fill the aisles of the church - a slightly imposing brick structure with a confusingly angled roof that looks a bit like a gym from the outside, but has a warm and welcoming feeling once inside.

"Christmas is a time to come together as a community, it is a time of togetherness and reflection," notes Dako, taking a break from choir rehearsals.

Father Dako is the leader of the Chaldean community in the UK.

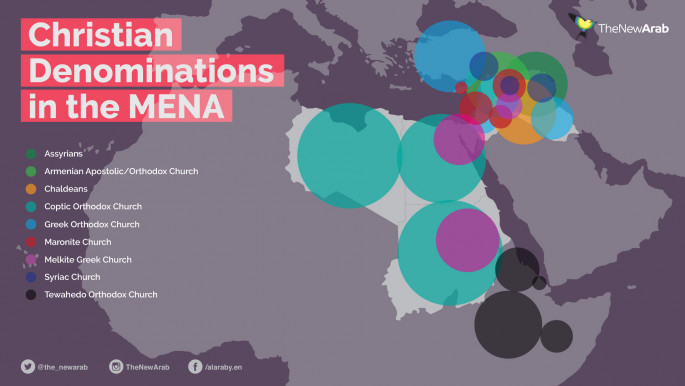

The Chaldean Catholic Church is one of a number of Assyrian churches whose adherents trace their roots to the Aramaic-speaking, biblical-era Assyrian empire.

It ruled over much of modern-day Iraq, in addition to areas of north-eastern Syria, south-eastern Turkey, and north-west Iran.

The Chaldean Catholic church emerged following a schism in the Assyrian church in the 16th century joining in communion with the papacy in Rome.

Meanwhile the Assyrian church - which maintains doctrines concerning the divine nature of Christ distinct from Rome - remained independent.

The Assyrian church also has a branch in the UK, located in nearby Ealing.

|

| Click to enlarge |

Born and raised in Iraq, Dako left Baghdad three years ago having worked as a pastoral priest for 20 years.

He spent eight months in Rome undertaking clerical studies before moving to London to take up his current post.

"It takes time to get used to a new country when you move, the language, the culture, the weather," notes Dako, who speaks Aramaic, Arabic, and English, and began developing his Italian in Rome.

"There are different challenges in different places. But as a diaspora community we are all sad about events in our homeland."

Persecution and relocation

Currently Iraqi forces are battling the Islamic State group for control of the Iraqi city of Mosul, backed by an international coalition led by the US.

IS took control of Mosul in 2014 during a series of lighting advances across vast swathes of Iraqi territory launched from areas the extremist group had seized across the border in war-torn Syria. Millions of Iraqis fell under the the group's brutal puritanical rule in the process.

In Mosul - historically a cosmopolitan and religiously-diverse city - IS demanded that Christians in the city convert to Islam or pay a poll tax (jizya) to continue living in the area. Those who refused were told to leave or face death.

The vast majority left. One Iraqi Chaldean priest lamented at that time that as a result of the exodus in June 2014 no mass was held in Mosul for the first time in 1,600 years.

Elsewhere in Iraq, IS' campaigns targeting Christians and other minority groups - most notably the Yazidis - have been labelled tantamount to genocide.

"The intolerance we see in attacks on minorities and historical sites is so destructive," exclaims Dako. He shakes his head, saying he believes the roots of IS can be traced back to Saddam Hussein and the consequent ruptures in society brought about by the 2003 US-led invasion.

While working in Baghdad in 2006, Dako says both himself and his brother were subjected to threats of violence and kidnap.

|

| Iraqi Christians return to a church in the recently liberated town of Qaraqosh, 30 km east of Mosul, badly damaged by IS militants [AFP] |

A rise in religiously-motivated attacks following the 2003 US-led invasion saw numerous Christian clergy - including from the Chaldean church - kidnapped or killed, and several religious institutions targeted in bomb attacks.

Many of the attacks were perpetrated by IS' predecessor, al-Qaeda in Iraq.

As a result Dako's brother, and other members of the family left the Iraqi capital, relocating to Erbil, the capital of the semi-autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan region.

"It was safer there," Dako says, taking a seat on a pew in a corner of the church beside an icon of the Virgin Mary holding the baby Jesus.

But, after IS' capture of Mosul in 2014 - and the group's seemingly unstoppable offensives - some of Dako's relatives decided they no longer felt safe Erbil, lying just 85km away from the jihadi group's new bastion.

|

| Click to enlarge |

"They decided it was time. They planned to move to Australia," says Dako, explaining that many Chaldean Iraqis emigrated to Australia in the 1990s during Saddam Hussein's rule.

However, things did not go according to plan.

In order to facilitate their move Dako's relatives had planned to sell property they owned in Erbil to raise funds.

However, IS' expansion led to a massive devaluation in the Erbil property market making it near impossible to get a fair price.

"Our property decreased in value by half, some by more," notes Dako, with a rye smile.

"Half of my family left, the other half stayed in Erbil. But those that left are not in Australia. They are in Jordan, waiting for their visa [asylum] applications… It has been a while."

Future concerns and challenges

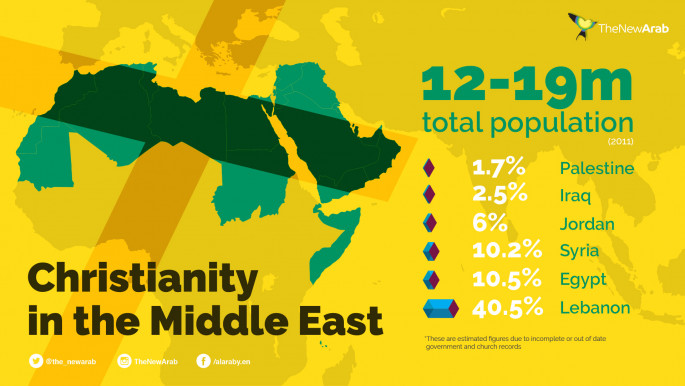

In the 1970s and 80s, Dako says there were over one million Chaldean Christians in Iraq. By the 90s this number had dwindled to around 500,000 in part due to domestic hardships brought about by international embargos placed on Saddam Hussein's Baathist regime, and the Gulf War.

Today, laments Dako, there are only 250,000 Christians of all denominations left in Iraq.

"Of course, when I visit I am happy to see friends and family, members of the church. But it is mixed emotions visiting at the moment given the situation."

Away from Iraq, acclimatising to the different needs of his congregation in the UK, Dako says, has proved both challenging and rewarding.

There are around 800 Chaldean families in the UK. The majority are based in London, with smaller communities located in cities including Birmingham, Manchester, and Cardiff - whom Dako visits each month.

"Here in the UK there are three generations of Chaldeans: the elder have maintained many traditions and practices, while the younger generation have adapted more.

"In Church services I speak in three languages for my congregation: Aramaic, Arabic, and English," explains Dako as a few more members of the children's choir trickle into rehearsal, and the organist replays the opening chords of Silent Night.

"The church does not meet as regularly as in Iraq. There is not as much interaction with the congregation on a daily basis, that is something that I miss. But Christmas should be a good gathering. I still have some things that I need to prepare."

Earlier, during a taxi journey from Dako's home to the church in West Acton, the Chaldean priest explained that on his last three trips to Iraq he has been unable to visit the graveyard where his parents are buried.

The town of Batnaya lies just 14 miles north of Mosul, and had fallen under IS control.

However, in October the IS-held town was liberated by Kurdish Peshmerga forces taking part in the assault of Mosul.

In the past few months, Christian clergy have returned to a number of villages liberated from IS. Poignant services have been held once again inside churches badly vandalised by IS militants; a glimmer of hope for the future of Iraq's ancient Christian community.

"I do not like speaking only about the Chaldean community in Iraq, my concerns and prayers are for all Iraqi Christians, and all those facing persecution," says Dako, with a look of steely resilience, before breaking into a warm smile.

"I am committed to my faith and committed to my mission."

Follow Martin Armstrong on Twitter: @MKLArmstrong

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News