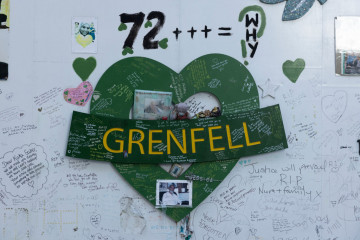

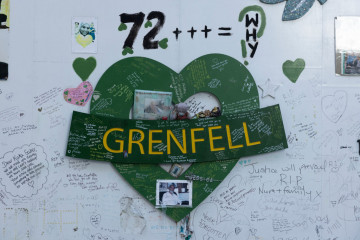

We’re constantly told Britain had an empire, but understanding Britain was an empire had been harder to explain. That was until Grenfell, the night our eyes changed.

Five years ago, a cocktail of British private industry and state deceit caused 72 people to lose their lives in a murderous act of neglect.

"George Floyd’s last words 'I can’t breathe' and breathlessness as a symptom of COVID-19 reinforce the idea that suffocation is a lasting metaphor for the globally oppressed"

In the minds of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, the residents of Grenfell Tower were misfits, undeserving of the council’s estimated £300 million budget surplus. They weren’t to be spoken to and certainly weren’t to be appeased in London’s most affluent borough.

In a country where race and class reign supreme, the lottery of birth meant the Grenfell residents were state-defined outcasts.

Eighty-five percent of those that died that night were ethnic minorities, 44 percent of those that died that night were of Middle Eastern origin and 20 percent of those that died that night were disabled.

When Michael Mansfield KC said the council saw Grenfell Tower as an “eyesore that required cosmetic surgery”, he wasn't only referring to the building itself.

We mustn't lose sight of how governance, the press, and wider society treated this community. Only after we take stock of the state's reaction to Grenfell do we realise this smearing isn’t new and hasn’t stopped.

In November 2016, eight months prior to the fire, the Grenfell Action Group issued a statement that “only a catastrophic event” would expose the “ineptitude and incompetence” of the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation - the body which owned the building. Nothing was done. 72 people died.

Yet Britain’s right-wing press still chose to demonize Grenfell's residents. Three days after the tragedy, The Daily Telegraph populated its front page with the headline: “Mustafa Al Mansur: Who is the leader of the Grenfell Tower protest movement?” The article went on to accuse Mustafa, a man with no prior convictions of terrorist-related offences, as a “terrorist sympathiser”.

This was a time when the state acted aggressively under the pretext of the “War on Terror”, a Britain still gripped by the Islamophobic hoax of the Trojan Horse Affair.

Further militarized by Brexit-laden sentiment, the silent majority were making sure their voices were heard.

In true Ballardian sense, the deeply sinister forces of Middle England – with its facades of bucolic country clubs and shiny labyrinthine malls – whirred into gear to lap up press narratives. Grenfell would be their next target.

Eight months after the Grenfell fire, five men were arrested for burning a model of the Grenfell Tower on a bonfire, shouting “All the little ninjas getting it” and “Help me! Help me! This is what happens when they don’t pay their rent.”

|

Britain is a nation that refuses to believe it may be to blame. Since the post-colonial movements of the mid-20th century - and the UK’s decision to recruit former subjects to rebuild the country – policy and procedure have been enforced to ensure foreigners know their place.

Encouraging perceptions of the “coloured” migrant have long been condoned. The 1962 Commonwealth Immigrants Act was the first piece of legislation which restricted the rights of citizens by affording racial discretion to immigration officers; illustrating a policy based on the fear of admitting non-white people rather than loyalty.

Winston Churchill’s proposed slogan of “Keep Britain White” in the 1955 election and Enoch Powell’s “Rivers of Blood” speech are further proof of a politics that mobilises ostensibly racist topics into broader themes of blame and exclusion.

So when the Leader of the House of Commons and Member of Parliament Jacob Rees-Mogg suggested those burning in Grenfell lacked “common sense”, it isn't lone wolf rhetoric, but centuries of engrained thinking where one group of people is better, smarter, and more deserving than the other.

Today, the British state retains the ability to craft its own image, in continuance of “the white man’s burden”. The nascent state of this thinking is injustice, with the government’s role to deflect, diffuse and direct the force of the law in any direction other than its own.

This remains the case with Grenfell. Each day, tens of thousands of motorists pass the burnt-out tower on their drive into central London, the white wrapping an embellishment of the council’s complicity. The public enquiry into how the fire took place is a £149 million-pound sham.

Were it not for the spirit of the North Kensington community and its allies, one could imagine a reality where Grenfell is no longer a talking point. Five years on, Grenfell is still an issue and will continue to be so.

Activists now join the dots from Grenfell to Gaza. Industries linked to human misery have been stormed. The UK-based group Palestine Action continues to occupy Arconic, the company responsible for the flammable cladding around Grenfell and the production of vital goods used in Israeli military aircraft.

It’s no coincidence that, in the years since the tragedy, a number of global movements have sprouted. George Floyd’s last words “I can’t breathe” and breathlessness as a symptom of COVID-19 reinforce the idea that suffocation is a lasting metaphor for the globally oppressed.

The UK government's proposal to outsource its refugee settlement infrastructure to Rwanda is a devious extension of a government that acts with impunity. One only has to read the MoU to see a leopard doesn’t change its spots. We saw that same disregard at Grenfell, we’re seeing it again today.

It’s therefore incumbent on us to protest and disrupt these policies, to stop them at their root. Grenfell is our focal point, proof that empire lies on our own doorstep.

By adopting a critical lens, we retain our ability to tease out invisible histories. As we have seen with Grenfell, our counter-narratives are, in fact, too integrated to be separate from the more dominant ones.

So, every time Grenfell Athletic FC. play, or the Hubb Community Kitchen sell timam bagila on Portobello Road, the spirits of those that lived in the tower live on. And in continuing their legacy, we will find out that our story is not the other story at all, but the story of the modern world.

Benjamin Ashraf is a Visiting Research Fellow at the University of Jordan’s Center for Strategic Studies. He is also part of The New Arab’s Editorial Team.

Follow him on Twitter: @ashrafzeneca

![Today marks the fifth anniversary of the deadly blaze at Grenfell tower that killed 72 people. A public inquiry condemned the London Fire Brigade's "stay put" strategy, in which emergency personnel told residents to stay in their flats for nearly two hours after the fire began [Getty Images]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2022-06/GettyImages-1402598395.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=jaCU4U73)

![Survivors, the bereaved, fire fighters and their supporters remember the 72 victims in the annual silent march [Getty Images]](/sites/default/files/styles/medium_16_9/public/2022-06/GettyImages-1323644908.jpg?h=69f2b9d0&itok=6xOmOU5O)

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News