LGBT+ refugees denied asylum if not 'flamboyant', study says

LGBT+ refugees face a better chance of being granted asylum if they play up to "flamboyant" stereotypes, a study has found.

Asylum seekers will also be more likely to be succesful in their claims if they can prove they have attended Pride marches, visited gay bars or participated in LGBT+ activism in their home countries, according to the research.

The new study, reported by The Independent, interviewed LGBT+ refugees from Tunisia, Syria, Iran, Lebanon and Pakistan seeking asylum in Germany.

Those who had the best chances of success had stories that "aligned with Western notions of queer/gay lifestyles", including the stereotype of "flamboyant" behaviour, frequent visits to gay bars or parties, public displays of affection, and wearing rainbow-coloured clothing, said Dr Mengia Tschalaer, of the University of Bristol, who carried out the study.

While the study refers to cases of LGBT+ asylum seekers in Germany, recent reports indicate that LGBT+ refugees seeking asylum in the UK also face difficulties attempting to "prove" their sexuality to interviewers from the Home Office.

The number of rejected asylum requests lodged by LGBT+ refugees has risen dramatically in recent years.

Last year, 78 percent of applications that referenced sexual orientation were denied by the Home Office - a 52 percent increase on figures from four years ago when 61 percent of LGBT+ asylum seekers were rejected.

Last year, two LGBT+ asylum seekers had their applications rejected in Austria on the basis that officials did not believe they were gay.

One Iraqi man was told he was "too girlish".

An Afghan refugee had his application denied after being told: "Neither your walk nor behaviour nor clothing indicate in any way you might be homosexual."

He was also told that fights he had with his roommates were evidence he was "aggressive", which "would not be expected of a homosexual".

Tschalaer's research suggests that those who were less open about their sexuality in their countries of origin were less likely to be granted asylum.

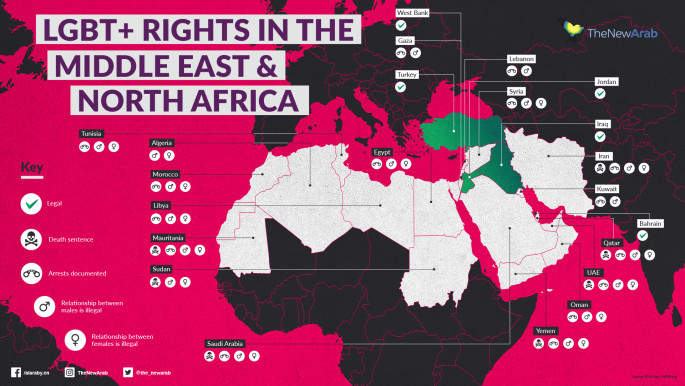

If true, that would pose difficulties for the vast majority of LGBT+ asylum seekers from the Middle East, Asia and Africa.

Many LGBT+ refugees seeking asylum in Germany, the UK and elsewhere would be unable to be "open" about their sexuality or engage in LGBT+ activism due to the criminalisation of homosexuality in their home countries, as well as the danger of being attacked or even killed for their sexuality.By definition, an asylum seeker is someone who is unable or unwilling to return to the country of their nationality due to a well-founded fear of persecution based on race, religion, nationality or membership of a particular social group or political opinion.

"LGBTQI+ asylum seekers who felt forced to hide their sexuality and/or gender identity, and who felt uncomfortable talking about it were usually rejected, as were those who were married or had children in their countries of origin," Tschalaer said.

"This was either because they were not recognised or believed as being LGBTQI+, or because they were told to hide in their country of origin since they had not come out yet."

Leila Zadeh, director of the UK Lesbian & Gay Immigration Group (UKLGIG), told The Independent that Western governments must stop "basing decisions on whether to grant asylum to LGBTQI+ people based on a person's ability to articulate a "coming out story’ in line with Western stereotypes".

UKLGIG's research also suggests that the Home Office sometimes refuses LGBT+ asylum applications to those who "find it hard to speak about their sexual orientation".

"This fails to recognise that in many parts of the world it is taboo to talk about emotions and relationships," she said."People who do not conform to a society's gender norms may never have spoken about their sexuality or gender identity at all."

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News