By blocking them and punishing those who aid them, Europe is drowning in migrants' blood

While a top UN official described that incident as "the worst Mediterranean tragedy" so far this year, this case sits on a mountain of countless other migrant deaths, as thousands have perished while attempting this treacherous route.

Europe must bear responsibility for these casualties, as it has sought to block aid ships working in the Mediterranean, while its efforts to block migration have increased illegal and dangerous smuggling methods.

This is nothing new, however. Europe has tried to curtail migration for decades, particularly after the Cold War. Its traditionally restrictive policies have garnered the term 'Fortress Europe', a critical term highlighting European attempts to block migrants from entering, where racism and xenophobia is often a driving factor.

Most European states have been complicit in 'Fortress Europe' in one way or another. From Poland's refusal to take any refugees, and Hungary's daunting southern border wall to block migrants, to Britain's attempts to contain the migrant flow through Calais.

Even towards Syrian and other refugees crossing through Turkey, the 2016 EU-Turkey deal has left countless refugees stranded in Greek islands, leading to a worsening humanitarian crisis in poorly equipped camps.

|

Europe's refusal and inaction in dealing with the ongoing Mediterranean migrant crisis worsens the humanitarian situation, leading to migrants taking more radical and dangerous measures to reach the continent |  |

Now, Europe's refusal and inaction in dealing with the ongoing Mediterranean migrant crisis worsens the humanitarian situation, leading to migrants taking more radical and dangerous measures to reach the continent. Vast numbers of migrant deaths have consequentially emerged, many are a direct consequence of European policies.

Seeking refuge from extreme poverty or violence, thousands of people flee their homelands in Western Africa via Chad and then through Libya, where they seek to cross the Mediterranean Sea to reach Europe.

Complicity in Libya

To counter this, EU governments have supported the Libyan coastguard financially and materially to block migrant ships leaving the country, as well as facilitating Libyan-run detentions centres.

In March the European Union moved to stop rescue sea patrols in the Mediterranean. Though air patrols will remain in place, to assist with the EU's Operation Sophia established in 2015 to allegedly prevent loss of migrant life, more deaths will likely take place without adequate protection.

Yet Europe's ambitions to reduce the migrant flow have actually led to increased smuggling, though moves like Operation Sophia were designed to prevent such illegal trades.

As Chad and Libya have effectively tried to criminalise mass migration, prompted by pressure and large donations of Europe, this has only given further rise to more illegal methods to aiding migration. While smuggling across the Mediterranean receives more attention, Chad has also reportedly become a hub for smuggling migrants.

"If people had access to safe and legal asylum processes, there would be less reliance on smuggling. Yet because of efforts to criminalise the migrant flow and block asylum seekers from reaching Europe, they feel it is necessary to resort to these dangerous measures," said Caroline Abu Sa'da, general director of SOS Méditerranée, an NGO whose sea rescue missions previously halted following pressure from European authorities.

Crackdown on 'good samaritans'

Other states have taken harsh measures to curtail NGO activities, particularly Italy, whose authorities sought to end the operations of the German NGO Sea Watch. There were subsequently no rescue ships working in the Mediterranean Sea.

While Italy has for many years sought to curtail the migrant flow from Libya to its own shores, last years' election of the far-right Five-Star-movement and Lega Nord (Italian Northern League) coalition hardened its anti-migrant stance. Deputy Prime Minister Matteo Salvini has sought to block migrant boats from docking on Italian ports.

Caroline Abu Sa'da however said while Italy was in the wrong, there is excessive focus on its role in the crisis, while ignoring the restrictions and general inaction of the rest of Europe, which significantly drives the humanitarian crisis.

"While it is convenient to portray Salvini as the sole villain here, most European states have in one way or another tried to restrict migrants from crossing," she said. "Spain for instance has imposed a 1 million Euro fine on migrant boats attempting to dock there."

"Salvini's statements that the rest of Europe needs to take its fair share of migrants, and for the EU to equally distribute the arrivals across member states, should be heeded by European authorities," added Abu Sa'ada.

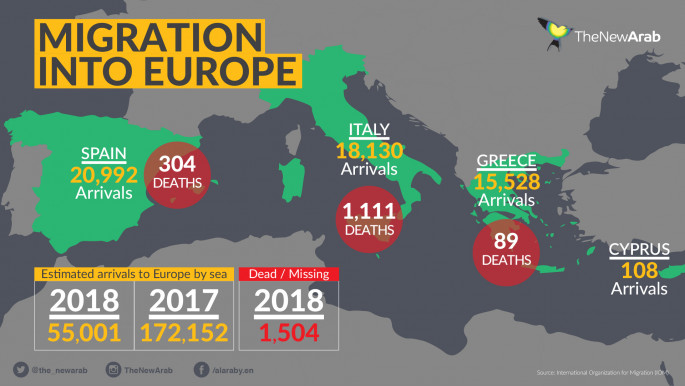

Article continues below infographic

EU laws such as the Dublin Convention, which entails that the first country an asylum seeker arrives in must process their application and host them, have clearly lead to a failure of practical distribution.

That central and northern European countries such as Switzerland support the convention, where migrants do not first land, leads to a failure of equal distribution, added Abu Sa'da.

Meanwhile, Europe's harsh restrictions leave migrants trapped in Libyan detention camps – which the EU and its member states have poured millions of euros into. Detainees face being sold into slavery by criminal gangs, beatings, sexual abuse and other forms of torture.

Europe knows the horrors that migrants face. Yet despite European authorities providing support to improve their conditions, Human Rights Watch reports that they have made little visible improvements.

Targeting migrants

Worsened fighting from warlord Khalifa Haftar's ongoing assault on Tripoli in April a further danger to migrant lives. One of Haftar's airstrikes in early July had already hit a detention center in Tajoura, near the capital, killing over 40 migrants.

Knowledge of the growing Mediterranean humanitarian catastrophe, particularly after the EU was sued at the International Criminal Court in June, is seemingly forcing greater action from certain European figures.

French President Emmanuel Macron declared in late July that 14 European states were closing in on an agreement to redistribute refugees. Among these included France, Germany, Finland, Luxembourg, Portugal, Lithuania, Croatia and Ireland.

Though a positive step forward, Caroline Abu Sa'da said that "this step needs to be implemented quickly for it to be effective."

"However, I don't think that European leaders realise the urgency of ratifying this agreement," she added.

Despite propaganda from anti-migrant, far-right political factions across Europe, European policy has tried to block entry to migrants and refugees, rather than giving them free entry.

To prevent further unnecessary loss of life, as well as an increased problem of smuggling which counteracts Europe's supposed policies of ending this, Europe should reassess its stance.

It should put humanitarianism, rather than lowering the numbers, at the forefront of any policy. This means ending the restrictions of aid organisations to operation in the Mediterranean Sea for starters, which would prevent such horrific casualties reoccurring.

Follow him on Twitter: @jfentonharvey

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, al-Araby al-Jadeed, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News