I survived Assad's extermination facilities, but only just

On 3 May, the US House Foreign Affairs Committee passed the amended Caesar Syria Civilian Protection Act of 2017 to impose sanctions on supporters of Syria's Assad regime, and to support the prosecution of war criminals, as "a step toward regaining leverage and imposing accountability for Assad's flagrant violations of international norms and human decency".

This Act was named after a Syrian military defector code-named Caesar, who smuggled around 50,000 photographs out of Syria. The images were of victims of torture and starvation who died in detention, and constitute a damning body of evidence of crimes against humanity in Syria by the Assad regime.

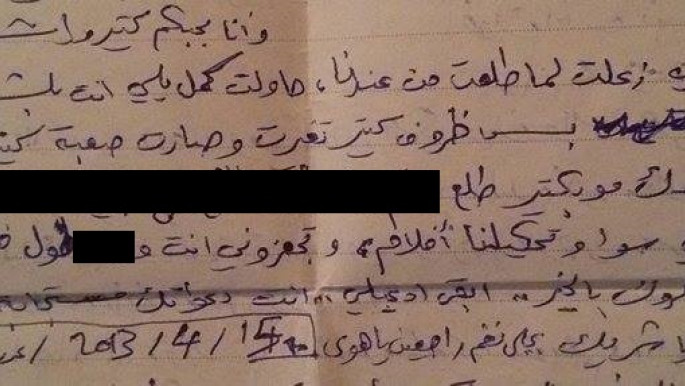

In March 2011, the Assad regime began throwing Syrians in an underground torture archipelago, subjecting them to arbitrary arrest, torture, and enforced disappearance. It's been long six years during which thousands and thousands have died in detention, and thousands more were executed in Saydnaya prison after they survived the first phase of their agony in the intelligence and military detention centers. It's been long six years since Assad started running extermination facilities, in which I was thrown for almost a year. I barely survived.

Before I was pulled out of the cell, my cell mates said to me, while hugging me and crying happily for me: "Please don't forget us, let the world know what it is like down here, please help us out!"

When I stepped out of the steel gate, it was not easy for me to walk like I used to. Not only because I had injuries in my legs from torture, and a weak body from lack of food and sunlight, but also because I forgot how to walk normally; it had been nine months since I walked last time, before I was thrown in a cell underground. The cell was overcrowded, and we took turns to sleep or even to sit.

|

When I stepped out of the steel gate, it was not easy for me to walk like I used to |  |

One of the scenes that we imagined happily was the simple joy of walking down a pavement! We dreamt of basic things that we take for granted in our daily lives; the physical act of being able to put one foot in front of the other.

Days and nights passed. I lost all hope that I would survive this ordeal. My hope turned into mere wishes and dreams that I would be released. I even said to myself that the army would never free me, because of what it had done to me, and what I witnessed of their crimes: They would be too concerned that I would tell the world what is happening down there, in Damascus, in the other Damascus that is underground.

Many of my cellmates were not lucky as me and are still languishing underground, with no real food, ventilation, light, medicine, or access to lawyers or families. Of those who are subject to daily torture and beating, dozens die every day. If they are not killed by the interrogators or jailors, they die because of infections, wounds and diseases.

The human body has a threshold for withstanding such severe conditions, and the average life expectancy inside those cells is just one year.

|

The average life expectancy inside those cells is just one year |  |

In March, a European parliamentary delegation headed by the Deputy Chairman of the European Parliament's Committee on Foreign Affairs Javier Couso, visited Assad and "confirmed their intention to proceed with their efforts …to continu[ing] work towards restoring diplomatic relations between the EU states and Syria, and towards lifting the sanctions imposed on Syria".

They stood with Assad, who is accused by the UN and many governments of war crimes and crimes against humanity, including the use of chemical weapons killing hundreds in few hours. Though the UN waited for six long years to state in March that Syria has turned into torture chamber, it had no suggestions for moving forward.

| Read more: 'Assad's torturers told me I'd hang by my fingernails' | |

Ignoring all this, the EU delegation members sat above tens of thousands of human beings languishing in detention centres underground. It is the other city under Damascus, a city of torture.

I am sure the delegation has not heard their silenced voices, but also, I can tell you that if those EU representatives had listened carefully, they would have heard the sounds of torture, the shouts and cries by human beings just like them, and only a few metres below.

I assure you that if any of those respected EU representatives looked from the window behind them, they would have glimpsed the ascending souls of children, doctors, students, journalists, and innocents, while they were well-received in Assad's palace.

|

Ignoring all this, the EU delegation members sat above tens of thousands of human beings languishing in detention centres underground |  |

The US act is a step forward, but we still done nothing to save even one detainee. The EU has done nothing to help save the lives of those calling out, bar sending delegates supporting the legitimacy of their killer.

Still, I believe in the shared basic values we human beings have, and I have hope that the western world will stop ignoring the secret and horrific massacre that continues.

The case of the detainees is not a political issue, nor is a matter for negotiation, it's a simple case of humanity, and it's not that complicated: Human beings are held in documented facilities, and the UN, human rights groups and many governments know the locations of those extermination cells operated by Assad's government and security establishments. The UN's role is not only to define a crisis, but also to work to stop it.

Vasily Grossman, the Ukrainian journalist who collected some of the first eyewitness accounts in 1943 of what later became known as the Holocaust, once said, "It is a moral duty to speak on behalf of the dead, on behalf of those who lie in the earth."

Now with all the evidence we have, including Caesar's photos and the urgent necessity to save those who are still alive, with many dying every day, there is also a legal duty to act.

I know the souls of those who passed tortured underground, are hovering over us, they are perhaps comforted now they are set free, but I am sure they are angry, they are haunting me, shouting: Keep going, keep telling the world about them, your silence is a crime no less.

Mansour Omari is a Syrian journalist and Syria correspondent for Reporters Without Borders.

He is the author of Syria Through Western Eyes: In-depth look on the Western reporting on Syria in 2013-2014. He has written for publications including The New York Times, The Daily Beast, Apostrophe and several Syrian media outlets.

Follow him on Twitter: @MansourOmari

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News