Containing nearly 41% of the world’s population, the BRICS (Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa) bloc represents a quarter of global GDP and 16% of international trade.

Recently, along with Turkey and Argentina, Saudi Arabia has shown interest in joining, and the addition of these countries will be on the agenda of the next BRICS summit scheduled to take place in South Africa in 2023.

As relations with Washington take a sour turn of late, Riyadh is now exploring new options to extend its geopolitical influence. Though the US and Saudi Arabia have long been close allies, their bilateral ties have weakened since the Biden administration came to power and voiced criticism over the Kingdom’s human rights record.

In addition, the murder of Jamal Khashoggi in 2018 put Riyadh in a corner after US intelligence agencies discovered links with the Saudi government. Fearing political ostracisation and isolation, Saudi Arabia started searching for new allies in the East to balance the Western world.

"While still geopolitically dependent for its security on the US, Saudi Arabia has geoeconomically shifted to the East"

But will keeping its options open help Riyadh replace Washington, and can it derive any worthwhile benefits?

To start with, where joining the BRICS is concerned, Riyadh’s move would bring it closer to Beijing’s orbit, as according to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) China accounts for almost 70% of the group’s economy.

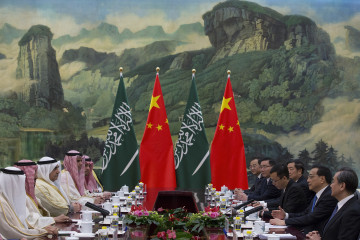

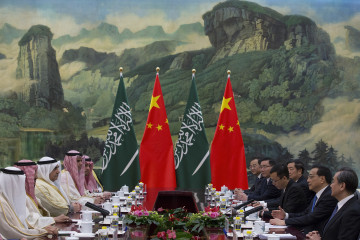

Amid the ongoing rivalry between Beijing and Washington, any spat between the US and Riyadh could provide China with more opportunities to extend its influence in the Kingdom.

In response to reports that the Saudi Crown Prince Mohammad bin Salman (MbS) had expressed intentions to join, Chinese spokesman Wang Wenbin announced that “China supports and welcomes this”.

Expected to compete with the economies of the richest countries by 2050, according to the banking group Goldman Sachs, the BRICS group is showing rapid economic growth, contributing 25% of the world’s total economic output.

At the 14th BRICS Summit in July this year, new possibilities for economic cooperation were discussed, such as a new development bank, an inter-country payment system, an exclusive BRICS basket reserve currency, and a contingent basket reserve currency.

“While still geopolitically dependent for its security on the US, Saudi Arabia has geoeconomically shifted to the East,” Mohammadbagher Forough, Research Fellow at the German Institute for Global and Area Studies, told The New Arab.

“China is right now the top trade partner of the country. India and Russia are becoming increasingly important to it as well (for different reasons). Given these developments, it's only natural that the Saudis would want to join BRICS+ or SCO.”

Highlighting the advantages of this move for Saudi Arabia, a Beijing-based international relations expert told Chinese media, “The idea of joining BRICS shows Saudi Arabia’s growing autonomy in its diplomacy with Washington”.

|

|

He added that “joining BRICS will also protect Saudi Arabia’s own energy interests in a substantive way, rather than being a card to be used by others”.

Next, there is the Moscow factor. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has made even minimal restructuring of foreign policy an uphill task for most countries. Though advantageous, achieving neutrality is much more difficult than in the past.

Even though the addition of more countries into the BRICS group requires some time to formalise, it has been compared to the planned expansion of NATO, largely because Moscow is part of the economic group.

In addition, Riyadh’s increasing support for Russian interests had already tested the basis of the Saudi-US relationship at various junctures. Complicating matters further, no agreement could be reached with Washington on increasing oil production during President Biden’s recent visit to the Kingdom.

"An inherent paradox is that disengaging from each other does not suit either Riyadh or Washington"

Then in October, the Saudi-led OPEC+ cut oil production further by two million barrels daily. While this step must have helped Russia, it irked Washington even more as it could have spiked gasoline prices just before the American midterm elections.

As a result, it was reported that US President Biden has “no plans” to meet MbS at the G20 summit this month.

Lastly, Riyadh has been indulging in some ‘energy geopolitics’ of its own.

Discussing an independent oil strategy with two of its biggest customers, China and India, the Saudi energy minister visited New Delhi last month to discuss economic cooperation.

Meanwhile, after a virtual meeting with his counterpart Prince Faisal bin Farhan, the Chinese foreign minister Wang Yi issued a joint statement with Riyadh and praised the Kingdom’s “pursuit of an independent energy policy and its active efforts to maintain the stability of the international energy market”.

In recent months, Riyadh and Beijing have also been mulling over payments in Chinese yuan for Saudi oil. Such a move would likely have a minor global impact, however, as Sino-Saudi trade is worth nearly $320 million every working day while trade in USD is valued at around $6.6 trillion.

Alongside that, Riyadh is finally executing plans to set up a $10 billion oil refinery in Gwadar in Pakistan and a tripartite agreement between Riyadh, Islamabad, and Beijing is being considered. For further discussions, the Saudi Crown Prince is expected to visit Pakistan this month.

Therefore, the Kingdom’s pivot to Asia is progressing well, with the intention of securing long-term economic and strategic cooperation. However, an inherent paradox is that disengaging from each other does not suit either Riyadh or Washington.

If Saudi Arabia’s outreach to the East is completed, the US will look like it is losing its hold on the region as its traditional allies are slipping away. At least for now, the US remains the Kingdom’s main security guarantor, and this would be a major contradiction in Saudi Arabia’s quest for new allies.

"Riyadh's engagement with Asian countries can help in economic diversification and stable energy partnerships, but the Kingdom would have to give priority to Washington for its defence needs"

Though China has a “comprehensive strategic partnership” with the Kingdom, it does not specify any clear military role and it has similar contracts with several other Middle Eastern countries. Beijing did sign memorandums of understanding (MoUs) on nuclear energy projects with Riyadh and supplied it with ballistic missile technology and drones, but it has not provided the kind of security cover Washington can offer.

Riyadh’s engagement with Asian countries can help in economic diversification and stable energy partnerships but the Kingdom would have to give priority to Washington for its defence needs. Also, Washington and Riyadh share almost identical regional security interests.

At any time, terror threats can raise their head again, and Riyadh would look towards Washington for help. Only recently, Saudi and US agencies shared intelligence on an alleged imminent Iranian attack on energy infrastructure in the Middle East.

Therefore, despite some erratic phases, no long-term change can be expected in Saudi foreign policy towards the US, and it is likely both countries will go back to square one on important matters.

Sabena Siddiqui is a foreign affairs journalist, lawyer, and geopolitical analyst specialising in modern China, the Belt and Road Initiative, the Middle East, and South Asia.

Follow her on Twitter: @sabena_siddiqi

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News