Who was Avicenna, and what does he offer today's Iranians?

One Persian intellectual integral to Iran's national identity predates them all by hundreds of years, however: the eminent medieval polymath Avicenna [Ibn Sīnā], whose name remains a byword for science and self-reflection across a country that has adopted his legacy as part of its cultural heritage.

"I would rate Avicenna as one of the biggest minds of human history and a real example of a critical and humanistic tradition in Persian philosophy," Dr Arshin Adib-Moghaddam, a professor of philosophy at SOAS University of London, told The New Arab.

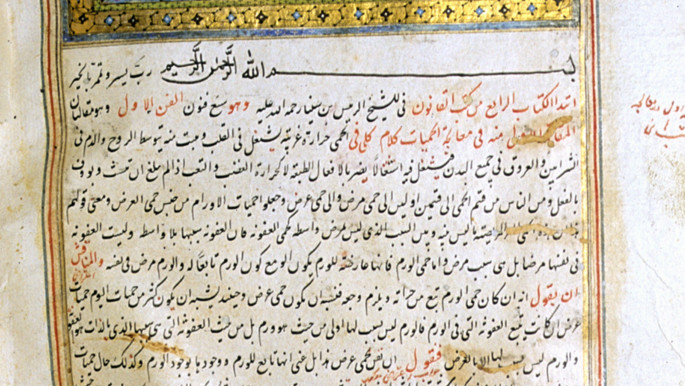

Born in the tenth century, Avicenna lived at the height of the Islamic Golden Age. He spent most of his life engaging with philosophy, science, and theology, having memorised the Quran at age ten and working as a physician by eighteen.

|

Born in the tenth century, Avicenna lived at the height of the Islamic Golden Age. He spent most of his life engaging with philosophy, science, and theology, having memorised the Quran at age ten and working as a physician by eighteen |  |

Avicenna's accomplishments in astronomy, medicine, and physics earned him a reputation as one of the Middle Ages' greatest scientists, but his claim that Muslims could interpret scripture through the writings of non-Muslim philosophers proved controversial.

Contemporaries such as the Persian theologian al-Ghazali praised the intellects of Avicenna and his fellow travellers, yet al-Ghazali also condemned Muslim philosophers' embrace of Aristotle, Plato, and other non-Muslims as dangerous and even heretical.

Avicenna's philosophical ideas never managed to gain as much traction among Muslims as his scientific ones in the centuries after his death.

A similar fate befell most other medieval Muslim philosophers, from the Persian logician and scientist al-Farabi in the Middle East to the Andalusian jurist and physician Averroes in the Maghreb.

Reactions to Avicenna appear to have changed by the twentieth century. Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, Iran's last monarch, hoped to stoke Iranian nationalism in 1953 by overseeing the construction of the Avicenna Mausoleum in Hamedan, where the Persian polymath spent the last years of his life.

The decades after the Iranian Revolution further cemented Avicenna's status as an Iranian cultural icon. In 1989, Grand Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini sent Mikhail Gorbachev a letter encouraging him to read Avicenna's philosophical treatises.

Criticism from several of Khomeini's colleagues, who opposed his reference to a philosopher described as an infidel by al-Ghazali, seems to have done little damage to the late supreme leader's legacy. In fact, Avicenna's ubiquity in Iran has only grown since then.

"Ayatollah Khomeini himself taught the theories of the classical philosophers at the seminaries in Qom before his forced exile to Turkey and Iraq in the 1970s," noted Adib-Moghaddam.

Hamedan hosts Buali Sina University, and Tehran has the Avicenna Research Institute, which itself contains the Avicenna Biotechnology Incubator and the Avicenna Infertility Clinic. The research centre also runs The Avicenna Journal of Biotechnology.

Other Iranian medical journals named after him cover biochemistry, dentistry, herbalism, and medical microbiology, indicating Iran's national pride in his scientific legacy. According to a popular Iranian-American Twitter account, Hamedan University of Medical Sciences graduates even held their ceremony at the Avicenna Mausoleum.

"Avicenna has always been prominent in contemporary Iran, both as a major philosopher and scientist," said Adib-Moghaddam, author of Psycho-Nationalism: Global Thought, Iranian Imaginations.

|

Ayatollah Khomeini himself taught the theories of the classical philosophers at the seminaries in Qom before his forced exile to Turkey and Iraq in the 1970s |  |

"After the revolution this trend continued. Today, Iranian politicians refer to Avicenna almost on a regular basis in order to highlight the philosophical heritage and scientific prowess of the country."

Despite the apparent rise in Avicenna's name recognition in Iran, the extent to which his legacy has influenced the country's national consciousness at a deeper level remains a matter of debate.

"There seems to be no direct link between Avicenna and public culture in Iran, maybe because in Middle Eastern societies – unlike the Western experience – philosophy has never been the basis of civilisation," said Dr Ahmad Bostani, an assistant professor of political science at Kharazmi University, itself named after a prominent Persian polymath and one of Avicenna's scientific predecessors.

Today, the Persian philosopher remains a popular talking point for Iranians across the political spectrum. Grand Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, a hardliner and Iran's current supreme leader, will often take to the country's state-owned media to extol Avicenna's scientific discoveries as part of Iran's historical contributions to the Muslim world.

In 2004, reformist and at the time Iranian President Mohammad Khatami opened an international conference on the polymath to promote Iran's culture. Even so, these tributes have focused on Avicenna's role in the history of science, not political philosophy.

"Avicenna's philosophy is not attractive to the pro-regime theorists since, according to them, there is nothing useful in Avicenna that does not exist in Sadra," Bostani told The New Arab, questioning the former's political influence.

"Recourse to Avicenna by authority figures is just rhetorical, because Avicenna's philosophy is totally independent from political trends in post revolutionary Iran."

Iranian clerics who subscribe to Avicennism have rarely taken the philosopher's teachings in the same direction. Students of Avicenna range from Mehdi Haeri Yazdi, who challenged Khomeini's reading of Shia Islam, to Mohammad Taqi Mesbah Yazdi, an ultraconservative supporter of Khamenei.

|

Today, Iranian politicians refer to Avicenna almost on a regular basis in order to highlight the philosophical heritage and scientific prowess of the country |  |

"Avicenna's philosophy has not been intellectually reworked as a potent critical theory to inform those themes," said Adib-Moghaddam.

"In his philosophy there is a radiant source of renaissance thinking that could inform the humanistic tradition that is at the heart of Persian poetry and philosophy."

These disagreements illustrate the complexities of Avicenna's legacy in Iran, which has accepted him as part of its national mythos but wrestled with the meaning and relevance of his guidance.

"Avicenna's philosophical system is quite complicated and multifaceted," Bostani told The New Arab, noting the varied interpretations of his esoteric writings.

"There is no consensus among Muslim scholars and intellectuals regarding what Avicenna's legacy has been for contemporary Iran."

Austin Bodetti studies the intersection of Islam, culture, and politics in Africa and Asia.

He has conducted fieldwork in Bosnia, Indonesia, Iraq, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Oman, South Sudan, Thailand, and Uganda. His research has appeared in The Daily Beast, USA Today, Vox, and Wired.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News