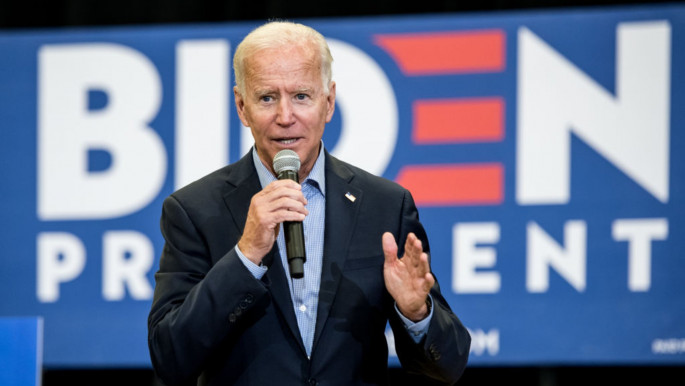

Can a Biden-Harris ticket fix America's broken Middle East policy?

But for those in the region, who have lived through wars, occupations, sanctions, infringements on their elections, freedom of movement, and inequitable economic policy, fair US foreign policy can mean the difference between a difficult and a dignified life.

It can also mean the difference between the US being seen as a fair or a biased power broker. In today's environment, there is little expectation of the US being fair toward much of the Middle East in its foreign policy.

It has been at least 60 years since the US has been widely seen in a positive light in the region. However, under Biden, there would be expectations of a focused and functioning foreign policy, signs of which can be seen from his time as senator and vice president.

"It's interesting that we have a candidate whose foreign policy is not unknown. He has been very involved in foreign policy and the Middle East," says Paul Salem, president of the Middle East Institute in Washington, DC. "A starting point would be that the Biden presidency would leave off from four years ago under Obama."

|

Under Biden, there would be expectations of a focused and functioning foreign policy |  |

Indeed, Biden has more than four decades of history in political office, as chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and then as Barack Obama's vice president.

Salem adds: "The challenge in the meantime is you've had four years of Trump and the Covid-19 crisis. When he takes office, God knows what condition the Middle East will be in."

Vice presidential candidate Kamala Harris

As the new partner on the ticket, Kamala Harris's addition to Biden's foreign policy team will likely come from her time in the senate, where she has served on the Senate Select Committee on Intelligence, and the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee.

Moreover, as the daughter of immigrants (from Jamaica and India), Harris has been an outspoken critic of the current administration's family separation policy, which she spoke about on the senate floor in 2018. She has also been a vocal critic of President Donald Trump's Muslim ban.

Her votes as a junior senator related to the Middle East reflect her relatively consistent liberal voting record. This year, she was a co-sponsor of "a joint resolution to direct the removal of United States Armed Forces from hostilities against the Islamic Republic of Iran" (which failed to override the presidential veto). However, in 2017 she voted for sanctions on Iran (with nearly unanimous congressional support).

|

|

In 2019, she voted for a joint resolution to prohibit the issuance of export licenses to the United Arab Emirates (UAE) for drones for its military. That same year, she voted for a resolution disapproving of license issuing for materials for a bombing program in Saudi Arabia. She also voted for a resolution for the removal of US armed forces from hostilities in Yemen that has not been approved by Congress.

She voted in 2018 against the extension of FISA, which authorises warrantless surveillance of non-US citizens outside the US (which failed). She voted in 2017 against the nomination of Mike Pompeo for Secretary of State (which also failed).

That same year, she voted against the nomination of David Friedman - a former Trump lawyer and campaign donor, who oversaw the move of the US embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem- for US ambassador to Israel (which failed). She also opposed the nomination of Rex Tillerson for secretary of state (which failed).

|

Despite her generally liberal voting record, Harris has shown a much harder line on the Israel-Palestine conflict than many of her Democratic colleagues |  |

Despite her generally liberal voting record, Harris has shown a much harder line on the Israel-Palestine conflict than many of her Democratic colleagues. In 2017, she co-sponsored a Republican-led resolution to revoke the role of the United Nations in the Israeli-Palestinian peace negotiations.

Signs of what is to come

There are already early steps in developing a pre-election democratic platform, unusual at this point in the election cycle, but a sign that the party would waste no time if elected.

In July, the Democratic-led House passed the No Ban Act, a bill that would repeal the travel ban on 13 countries. Though it currently doesn't likely stand a chance in the current Republican-majority Senate, this could set the tone for what is to come for a potential Democratic White House win.

|

|

| Read more: The race for Biden's foreign policy agenda |

Behind the scenes, Biden has assembled a foreign policy team that is already getting ready to hit the ground running on day one. They include experts in the fields of human rights, environmentalism, social justice and LGBTQ issues. This appears to be a promising start, but not without cause for concern from the left wing of the Democratic party.

A letter circulated at the beginning of August, signed by more than 275 Bernie Sanders delegates, raises alarms over some of Biden's foreign policy team due to their past and present conflicts of interest.

These include: Anthony Blinken, who co-founded a company involved in drone warfare; Michèle Flournoy, who worked at Boston Consulting Group, which has major military contracts; Avril Haines, a former CIA deputy director, who was involved in targeted killing programs; and Amit Jani, who currently runs Asian American outreach for Biden and has connections to right-wing Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

It remains to be seen how open Biden would be to re-evaluating these roles. So far, it appears that he wants to bring together a similar team as what he had in the Obama administration. This included roles in conflicts as well as in diplomatic negotiations.

Iraq

Biden is probably best known in the region for leading the push for Congress to vote for the 2003 invasion of Iraq. What is possibly less known is his subsequent criticism of the occupation and his calls against a US troop surge, once he saw fallout from the US military occupation of Iraq.

|

The invasion of Iraq is largely seen as America's biggest foreign policy mistake since the Vietnam War |  |

Nevertheless, the invasion of Iraq is largely seen as America's biggest foreign policy mistake since the Vietnam War. When tasked with the Iraq portfolio as vice president, Biden supported the controversial sectarian leadership of Nouri al-Maliki. He also oversaw the withdrawal of troops from Iraq, which was followed by the rise of the Islamic State (IS).

If Biden becomes president, he will be dealing with a divided Iraq in political and economic turmoil, as well as the potential for the rise of sectarian militant groups to fill the political void. An important part of easing tensions in Iraq will be improving relations with Iran, which the US has neglected in recent years.

"The US needs better relations with Iran to calm tensions in Iraq," says Stephen Pampinella, assistant professor of political science and international relations at State University of New York at New Platz.

Israel/Palestine

Like most US politicians, Biden has consistently been a solid supporter of Israel. Nevertheless, he has the distinction of being the first US presidential candidate to be endorsed by J Street. The liberal Jewish lobby group made the announcement in April, along with a pledge to donate a total of a million dollars to his campaign by November.

"Biden has long championed many of J Street's most important priorities, including a just and peaceful resolution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict," J Street's president Jeremy Ben Ami said in a public statement. "He helped spearhead overwhelming support for Israel's security alongside clear opposition to settlement expansion, creeping annexation and other measures that undermined the prospects for Israeli-Palestinian peace."

|

|

| Read more: Pro-Palestine Democrat wins reveal weakening influence of Israel money |

It is unclear if this endorsement is meant to reward or influence Biden's policy. It is a possible indication of a growing nuance on Israeli policy within the Democratic party, a counterweight to an increasingly hardline AIPAC (the main Israel lobby group), or a message of solidarity against Trump, considered by many moderates and liberals alike as a dangerous fascist.

So far, Biden's position on Israel continues to be mainstream (by US standards), and there is no indication of this changing. He says he supports a two-state solution and opposes the annexation of the West Bank. However, he also calls himself a Zionist, has called the Boycott Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movementanti-Semitic, and says he would keep the US embassy, that Trump moved, in Jerusalem.

In fact, as senator back in 1995, Biden voted for the Jerusalem Embassy Act, which recognised Jerusalem as Israel's undivided capital. President Bill Clinton was afraid this would derail the peace process, so he added a six-month waiver (instead of vetoing the bill, which would likely have been overridden), meaning the president could avoid moving the embassy on national security grounds every six months, which all of them have done, until Trump took office.

|

Biden would likely not want to test US policy in Israel, particularly after seeing the challenges Obama faced while in office |

|

Given his history, Biden would likely not want to test US policy in Israel, particularly after seeing the challenges Obama faced while in office.

"With Obama's relationship with Israel, he saw a contentious relationship he had with Netanyahu. I don't think Biden is willing to challenge Netanyahu," says Pampinella. "He supports a two-state solution, but he could allow more settlements. He would criticize it, but probably not take action."

Afghanistan

Aside from his own policies, Biden is also known for those of Obama from his time serving as his vice president. This includes the prolonged war in Afghanistan, now the longest war in US history, which started under George W. Bush following the 9/11 attack on the US in 2001, though US involvement in the country goes back to the Cold War when it supported the mujahideen against the Soviet Union.

Biden would likely continue where Trump left off with peace negotiations with the Taliban. "In Afghanistan, I would expect the administration to continue negotiating with the Taliban. What they'd want to do ideally is to include a peace agreement. They'd want to announce the US leaving Afghanistan, consistent with Biden's long-standing position on Afghanistan," says Pampinella.

|

|

| Read more: The Trump effect on global press freedom |

"He thought counterinsurgency was bad idea, and he wanted to focus on counterterrorism. He wants to go back to a skeletal military force that could engage in operations against the Taliban. I think they'd attempt to bring other states from the region into the process," he says.

Yemen

Yemen is important, not only because of its severe humanitarian crisis – unprecedented levels of poverty and hunger – but also because it relates to America's relationship with the Arab Gulf states and Iran, who are fighting against one another in Yemen's civil war.

Biden has called for an end to US support for the Saudi-led war in Yemen. He has also said the US should re-evaluate its relationship with Saudi Arabia, following the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi, but has provided few other details.

"Biden has already said he would end any US involvement of the Saudi role in the war in Yemen. But would the US continue military aid to Saudi Arabia?" says Pampinella.

It is also unclear how or if Biden would continue the controversial US drone and other aerial strikes on Yemen (as part of America's war on terror), which began in 2002, then increased significantly under Obama, and then increased further under Trump. According to The Bureau of Investigative Journalism, in the first two years of Trump's time in office, there were more confirmed US strikes on Yemen (163) than in Obama's entire eight years (154).

|

Biden has already said he would end any US involvement with the Saudi role in Yemen's war. But would the US continue military aid to Riyadh? |  |

Qatar

Few predicted that the blockade on Qatar would last as long as it has. With some of the world's biggest US military bases, a wealth of natural resources and other US interests in Qatar and its rival neighbours, it is likely Biden will follow his predecessors and not take sides.

Syria

Obama's policy in Syria could be characterised as a hands-off approach in which he probably didn't want to be seen as a regime changer, as he was following a president who led the US into the unpopular war in Iraq. Even when the Syrian regime used chemical weapons on its own people, which Obama had said was a red line, the US did not respond. In addition, even before the Muslim ban, the US took in only a small number of refugees from Syria – tens of thousands per year (Over the past three years, that number has gone down to two figures).

"Two successive administrations have (with rare exception) declined to protect Syrian civilians from regime mass homicide, opening the door to extremist alternatives to a war criminal. A Biden administration would do well to focus on civilian protection," says Fred Hof, former US Special Envoy to Syria.

Since Obama left office, Syria has become even more fractured, largely run by outside powers - most notably Russia - that have filled the political void. "Russia is a rising power in the Middle East. Russia won the war in Syria full stop," says Cliff Kupchan, chairman of the political risk consulting and advisory firm Eurasia Group, where he specialises in Russia and Iran.

Moreover, Trump's sudden withdrawal of US troops from northern Syria last year will leave a potential Biden administration in a weakened position.

|

|

| Read more: US pressure pushes Iran into China and Russia's arms |

Economic policies

Although the US is much more known for its military and diplomatic policies in the region, its economic policies also have far-reaching effects, in some ways felt more widely than other policies (though not unrelated) due to the broad nature of sanctions, trade agreements and the dependence of the US dollar as the standard currency.

The US currently has varying types and levels of sanctions on around 40 countries throughout the world, including most conflict-torn countries in the region. The most severe apply to Iran and Syria, where almost all types of international trade and financial transactions are forbidden.

However, even countries with relatively decent relations with the US are affected by US sanctions and trade policies imposed on other countries. Since the US withdrew from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (also known as the Iran nuclear deal), the US has imposed billions of dollars in fees on Asian and European companies for their financial transactions with Iran due to the US dollar as the default international trading currency, one of many indirect consequences of the US leaving the multilateral deal.

Kupchan sees Iran as an important and challenging country for US policy. "Anti-Iran sentiment in the US is deeper than for any other country," he says, citing the hostage crisis of the late 1970s and the country's work on a nuclear program.

Nevertheless, re-entering the deal would likely be one of Biden's foreign policy priorities as president. "I think he feels ownership of the Iran deal," says Trita Parsi, Executive Vice President of the Quincy Institute for Responsible Statecraft. "A lot of folks who will go into his administration if he wins see Trump's action as beyond unfortunate."

|

The US currently has varying types and levels of sanctions on around 40 countries throughout the world, including most conflict-torn countries in the region |  |

He adds, "It would be a bad idea to renegotiate the Iran deal. Much indicates that Biden is leaning towards avoiding the mess that a renegotiation would cause and instead opt for a compliance-for-compliance formula. That is, both the US and Iran go back into full compliance with the deal. Any hint at a renegotiation will likely cause the Iranians to begin amassing leverage for such a negotiation by reducing their compliance even further."

Meanwhile, if Biden is elected in November, he will have to contend with China and Russia having expanded their economic reach in the region in the absence of US engagement. For most countries in the Middle East, China is the largest trading partner. Even Saudi Arabia and the UAE, long aligned with the West, have seen an increase in trade with Russia in recent years.

If elected, Biden will be starting his job with diminished US economic and diplomatic power in the Middle East – a trend that began at least two decades ago, and accelerated with hardline policies, such as its invasion of Iraq, its withdrawal from the Iran deal and its reversal from long-held positions with the Palestinians.

"It's clear from the past two decades that US military might does not translate into the desired impact on events. Military superiority is not what it used to be," says Parsi. "Much of that loss is the US playing its hand poorly. The US was overestimating its power, and it made colossal mistakes like invading Iraq." America's diminished power is exacerbated by its current diplomatic void.

|

|

| Read more: Iraq still in chaos 17 years after US invasion |

Diplomacy

There are currently around 20 countries and institutions without US ambassador vacancies (and another 20 nominations awaiting confirmation), five of which are in the Middle East. These include Afghanistan, Qatar, Sudan, Iran and Syria, with the latter two not having ambassadors due to a lack of diplomatic relations with the US.

Additionally, there's the UN Human Rights Council and UNESCO, both from which the US has withdrawn during the Trump presidency.

"If there is a Biden administration, it will be fully staffed and there will be fact-based foreign policy," says Kupchan. "You won't have all of these unfilled positions. This void has created policy that's not fully informed on facts."

Indeed, having fully functioning embassies will be key for US understanding what is happening in the region. "From the standpoint of the host government, dealing with the president's personal representative is vital. And for the interests of the US to be protected and advanced it is important for embassies to be fully staffed from the top-down," says Hof.

"The delay, for example, in posting an ambassador to Saudi Arabia unnecessarily courted policy disaster, as a young and inexperienced Crown Prince lacked the counselling services of a mature American ambassador."

In addition to the embassies in the region, there are also the United Nations institutions from which the Trump administration has pulled out – UNESCO and UNRWA, both because of their work in Palestinian culture and education. Biden has not made commitments about what he would do with these organisations, however if his inclination to keep the US embassy in Jerusalem is any indication of his position toward Palestinians, there might be little hope of the US renewing ties with these organisations.

On top of these open ambassador posts, the Qatar diplomatic crisis that started in 2017 will be another area that a new administration might hope to address, though it will likely remain a low priority.

Looking to 2020

With so much to address in the region, it might seem like a particularly bleak time to take the reins of the highest office in the US. On the other hand, it could also be a good time to reassess US policy in the Middle East.

"I think America is salvageable under Biden. Seventy percent of American policy can be restored," says Kupchan. "I think Biden will pursue a more mainstream policy. He's very knowledgeable of the region."

Brooke Anderson is a freelance journalist covering international politics, business and culture

Follow her on Twitter: @Brookethenews

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News