Turkey's compulsory Ottoman course causes controversy

A controversial attempt by the Turkish ministry of education to introduce the Ottoman language to the country's high school curriculum, has reignited a debate on Turkey's identity.

The extinct language was once the preserve of the Ottoman courts, who ruled over an empire covering modern day Turkey, the Middle East, North Africa and the Balkans. Reintroducing the language into schools, possibly mandatory, is a hugely contentious issue in a country

| What is this allergy for history? What is this enmity for culture? It is not possible to understand." - Ahmet Davutoglu |

that closely guards its secular values.

Secularism v Islamism

The step is seen by many as an attempt by the moderate Islamist government of furnishing Turkey with a Muslim, and not Turkish identity. The Ottoman Empire, although a source of pride for many Turks, is still identified with an archaic past when the country was ruled with Islamic rules and for the most part guided, in theory at least, according to the principles of the religion.

President Recep Tayyip Erdigan and Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoglu, as well as members of the opposition, have all waded into the fray, but the debate – over Turkish identity, history and the Islamisation of society – often seemed to obscure rather than clarify whether this was merely an attempt to lift out of academia an integral part of Turkish history and heritage and bring it into the classrooms.

Complicating matters, the Ottoman language, or 'Old Turkish', is a jumble of influences. Written with the Arabic script but spoken with a Turkish pronunciation and including words from Turkish, Arabic and Farsi, the language was – with low literacy rates – always the purview of the educated elites.

Most of the Ottoman Empire archives are written in this language, however, and historians are generally in favour of the idea, though sceptical about how to implement it, especially at high school level.

Classics in the classroom

Any such course should be carefully prepared, said Ilber Ortayli, a historian and Ottoman expert at Galatasaray University. He also suggested that the language should be taught as part of a general course on ancient western and eastern languages.

"The application of the project should be carefully planned. Rather than teaching it in regular high schools, pilot schools should be selected or opened for specialisation."

Moreover, realising such a course is challenging. Ottoman was not only restricted to the elite, it appeared to change over time, according to Nihal Arsoy, a specialist in the late Ottoman-era at the University of California, Los Angeles.

Arsoy is a pseudonym. She preferred not to give her real name.

"Not only are there many different styles of Ottoman writing, but the language is substantially different in different periods," said Arsoy, who spends most of her time in the Ottoman archives in Istanbul. "This constitutes a problem in deciding what exactly to teach students."

There is also a lack of qualified teachers for such a course and some experts suggested that high school was not an appropriate stage to introduce a specialised course.

"The real formation for gaining expertise on the language could only take place in universities," said Edhem Eldem of the history department of Bogazici University.

Most experts were broadly positive about the idea. Just as the teaching of Latin or Ancient Greek proves and advantage in the West to those who go on to study languages or history at university, academics say, so could Ottoman in Turkey.

Enter politics

But such academic debates about learning and practicality was largely lost in the political controversy that erupted when on 7 December the National Education Council of Turkey, a body under the National Education Ministry, called for the introduction of a compulsory course on Ottoman in high school.

In part, the controversy arose on a background of a number of changes that have been implemented over recent years that critics of Turkey's ruling Islamist Justice and Development Party (AKP) have derided as an attempt to Islamise Turkish society. Over the past 11 years, 13 major changes were made in the education system, including to secondary education curricula and rules on university entry exams.

Among them was a ruling to allow girls to wear headscarves in school, a radical proposal in a country founded on staunchly secular principles. Critics have also seized on the surge in numbers of those attending religious imam hatip schools and proposals – which brought the government a rebuke from EU for contravening the European Convention of Human Rights – to introduce compulsory religion classes as early as the first grade.

Currently, they are compulsory from the fourth grade.

In that context, opposition parties thus saw the council decision as another move to Islamise the country.

That accusation is also partly based on the reasons behind the 'letter and language' reforms of Mustafa Kemal Ataturk, the strongly secular founder of modern Turkey, that did away with Ottoman in the first place between 1928 and 1932.

The reforms replaced the Arabic script with Latin letters and simplified the spoken language by clearing out Persian and Arabic words and introducing Turkish ones. The goal, according to Yusuf Kaplan at daily Yeni Safak, was in fact to kill a living language and to sever ties with the Arab-Islamic world. Thus, the ruling elite of the early Turkish republic hoped to curb the influence of religion on the society.

Hence, too, the reasoning goes, the opposite would hold. Reintroducing Ottoman would increase the role of religion in society and aid, in the words of opposition politicians, the ruling AKP Party in changing the education system to raise a "devout youth".

The Republican People's Party (CHP) deputy parliamentary group chair Akif Hamzacebi also accused Erdogan of not only having a problem with the secular republican period, but also with the late Ottoman era, where education in the sciences became seen as necessary component of progress.

"Even the Ottomans wouldn't make these decisions," Hamzacebi said at a press conference two weeks ago.

According to Kadri Gursel, a columnist at daily Milliyet, the government's moves on education as "a manifestation of 'social engineering', which they have so fervently criticized in the past. The 'devout youth' is the carrier of Erdogan's 'New Turkey' paradigm. The generation to be raised under an Islamised education system is seen as the guarantor of the political Islam the regime is building in Turkey."

Erdogan batted off criticism with presidential scorn. "Whether they want it or not, Ottoman [language] will be learned and taught in this country," he said in December in Ankara.

Striking a slightly less strident tone, Davutoglu dismissed criticism as ill-informed and anti-Turkish history. In a recent press conference, the PM accused opposition leaders and CHP chairman Kemal Kilicdaroglu in particular of "acting with enmity towards their own history".

"What is this allergy for history? What is this enmity for culture? It is not possible to understand."

What about the children?

|

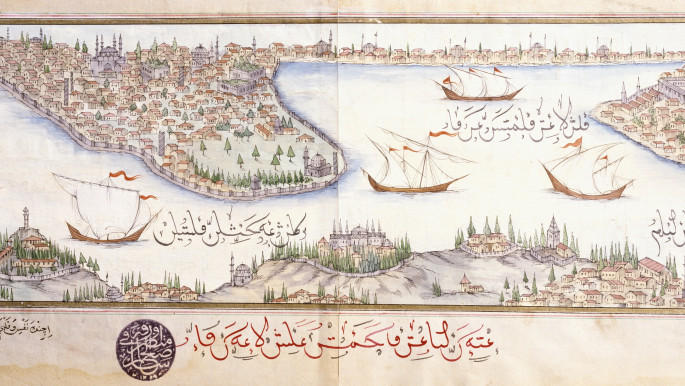

| Istanbul in an Ottoman miniature, 17th century (Getty) |

High school students themselves are divided. To some, the course would provide a new and welcome challenge. To others, yet another pointless exam on an already overloaded curriculum.

Lara, 15, a 10th grade student at Istanbul's Mumtaz Turhan Social Sciences Highschool told al-Araby al-Jadeed that she has been taking the course as an elective for the last two years. "It is like solving a puzzle, and very fun to decipher," she said. But she thinks that the course should remain an elective.

Another 11th grade student, Tuncay, at the private Kocaeli Doga School said before any other languages are taught, the government should prioritise good Turkish.

"Turkish language existed before the Ottoman language. As we are capable of understanding the language of pre-Ottoman times, then there is no need to learn a now extinct language," he argued.

And yet others thought it just another slog. Inci, 16, an 11th grade student at Cahit Elginkan Anatolian High school thinks the course should be an elective. "We are already under the pressure of an intense curriculum and we have to prepare for university entry exams. Learning a language that is not being used except by the experts is not contributing to my education."

No final decision on whether the course should be elective or compulsory has yet been made. But even academics supportive of the idea, suggest the government's motives were political. The government knows the appropriate human resources to actually teach the course are not there, said Eldem, so there is only one explanation for making the proposal now:

"The decision has nothing to do with either education or culture. It is a political move with the aim of undertaking an ideological project."

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News