'There's no more place for luxury': Lebanese persevere as country's economy worsens

"Five for one thousand lira (£0.50)," a man told people looking at the mountain of sweets situated near the entrance of the shop. In most other stores, the price for one of these candies would cost one to two thousand lira (£0.50-£1).

Throughout the rest of the store it is easy to tell that the prices of the vast majority of the products being sold are significantly cheaper than elsewhere. Coffee for 2,750 lira (£1.40). Shampoo for 3,500 lira (£1.78).

Outside of this shop, these sorts of prices have become nearly impossible to find due to the continued worsening of Lebanon's economy which has caused the price of most goods to increase.

"The whole of the Lebanese economy has been based on attracting remittances from abroad and giving hefty interest rates," Hala Bejjani, the managing director of Kulluna Irada told The New Arab.

"At the same time, choosing to peg the currency in order to offer some stability for these people that are going to send their money and doing expenditures that were, as a result of this, way beyond the needs of the country and, also, the capacity of the country."

|

The whole of the Lebanese economy has been based on attracting remittances from abroad and giving hefty interest rates |  |

Mohammad Al-Akkaoui, an economist with Kulluna Irada, added, "In the 90s, there was a decision to make Lebanon a tax haven to bring money into Lebanon whatever it takes. Tax rates were set low and enforcing taxes was relaxed.

"If you look at the government's tax revenues in 2018, not interest, they averaged 19 percent while the emerging market average was 27 percent," Al-Akkaoui said.

"When you don't collect as much taxes, you take debt. So the government issued debt, the banks bought the debt, ergo rich people bought the debt, and, then, the government started to pay interest for rich people," he added.

"Basically, what the government has done is pay rich people interest instead of taking taxes from them which created this really nice bubble to keep your cash and let it grow. In order to attract these depositors, they fixed the exchange rate to remove the currency risk to convince people to change their dollars into lira."

Since the establishment of Lebanon's economic system, there have been several instances where the country entered a small crisis. However, the system was not changed in any way and the issues that plagued the country persisted.

|

|

| Read also: Lebanon can save its economy, just not with the help of the IMF |

Now the country is facing multiple crises where the government could default on upcoming debt payments, the devaluation of the country's currency, the Lebanese lira, as well as a banking crisis.

"They are all linked to the currency crisis which is the crisis at the central bank," Al-Akkaoui explained.

"Four years ago was the first year that the central bank's reserves dropped significantly because the outlook accelerated rapidly. Back then the decision was made to give the government some space to do the needed fiscal reforms which is why the central bank created this entire financial engineering scheme. That was really the watershed moment for Lebanon there that chipped everything off."

He further explained that was when the crisis really started; 2011 to 2016 was still a period of pre-crisis, but the country was still moving.

"In 2018 the central bank realised that if it continued funding the government as it was, it was going to run out of reserves. So they just slowed the taps," Al-Akkaoui said.

"It also was the same year that the government failed to gain market access because it issued its budget which showed that it was not sustainable. Since 2018 until now, the sole financer of the government has been the central bank."

Read also: Lebanese no longer have confidence in state, PM admits amid debt crisis

The continued worsening of the economy is something that has affected the majority of the Lebanese population. Due to the economic crisis, more and more people are being fired from their jobs because their employers are unable to pay them.

One of these people was Roudy Hanna who worked as a business development executive until around three months ago when he was fired.

Since then, he and one of his friends have started Thawra Saj to sell food to people at Martyrs' Square in Downtown Beirut, a major centre for protests in Lebanon's capital.

"We've been looking for jobs over three months and we haven't found any jobs," Hanna told The New Arab.

"So, we decided to sell saj. We had no experience whatsoever, but it's common. Saj is very common here, so, we decide to try our luck and, thankfully, it has been almost a month and we're doing all right."

|

|

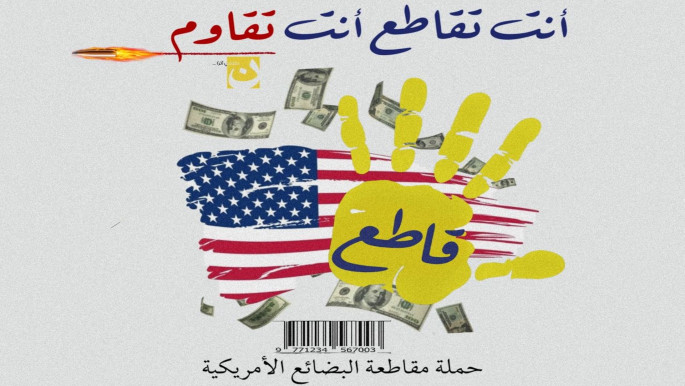

| Read also: Hezbollah wants the dollar-hungry Lebanese to boycott American goods. The catch? Lebanon could hurt more |

Around 40 percent of the Lebanese population is unemployed and that number is steadily climbing as employers have to further reduce their budgets.

According to Al-Akkaoui and Bejjani, the high levels of unemployment are caused by the lack of options for people who study at university, as well as the need to have people move abroad and be successful so that they can send money back to Lebanon.

"We don't create enough jobs and the labour market does not fit the demands of the Lebanese economy," Al-Akkaoui said.

"It's two things. First, we're dependent on imports which demand a low workforce and then, the second thing is because the educational system has not been evolving as it should. It does not meet the demands of the local and niche market which educates so many engineers and so many doctors."

Bejjani added, "We have been producing a labour force to export, but we're not producing a labour force just for our local needs.

"The Lebanese economy has always adjusted by emigration. We train people, we educate them at the very high cost, but, then, we send them abroad and this is how we have adjusted out unemployment."

However, due to the decrease in the value of the lira, some of the foreign work force that has come to Lebanon is now looking to leave.

"Now, with these cheap prices," Bejjani said, "one of effects of the prices is that we have not been able to pay these people in dollars and they will be leaving the country en masse, so we'll have another kind of crisis of not even being able to access the cheap labour."

|

While Lebanon's central bank has continued to say that the lira will remain pegged at the rate of one US dollar to 1,500 Lebanese lira, when people go to exchange their lira for dollars, they have found that the value of their currency has decreased by around half of what it was just several months ago.

At its height, exchange offices were selling dollars at one dollar to over 2,500 lira.

Due to the continued devaluation of the lira on the black market at exchange offices, many stores have started to raise their prices in order to cover the rise in costs.

"The prices were going up," Hanna recalled. "It was crazy. Our salaries were barley lasting us until mid-month, like two weeks, and poof. What the hell happened?"

Landlords have also began raising the prices of rent or have said that they will only accept payments in dollars.

"It used to be in dollars but we [me and my landlord] made a settlement and it became in Lebanese pounds," Hanna said.

"We agreed on something in-between [the official and black market rate]. He's not a bad guy, but he also has bills to pay. So, it's understandable."

Due to the rise in expenses, people are having to change their spending habits in order to get by. Hanna explained that he is now having to focus on only buying the bare necessities.

"We cut down on meat a lot. That's sad because I love my steak," he laughed. "I think that everyone is going through the same thing. We're buying the necessities. There's no more place for luxury."

Read also: Lebanon's post-Civil War generation flock to the streets without fear

However, not all of Lebanon's shops are raising their prices.

Hajj Abdul Nasser Shehaytli, owns a shop in Beirut's southern suburbs and sells most of his products at a cheaper rate than the larger stores with the majority of what he sells either coming directly from producers or being imported from cheaper countries like Turkey, Syria and Iran.

"We've been open since the speech [last month] by Sayed [Hassan Nasrallah] when he asked us to have mercy on people with the prices [for goods]," he told The New Arab.

"I've been in this business for 40 years and I know where to get the cheapest products that will benefit people the most. For example, the eggs I get are fresh from the farmers and not through a third-party seller. I sell them for 40 percent less than the supermarket price. The cheese and labneh are from our village and don't have any preservatives."

For Shehaytli, making a profit is not what is important right now. His main focus is making sure that people are able to eat and take care of themselves and their families as the economic situation continues to deteriorate.

"I sort of entered a storm with the dollar crisis and the economic issues," he said.

"Our store's profit ranges from four percent to seven percent and sometimes one percent. This is a family-run business – I have eight kids so we all work here to try to keep it running. We're getting so many customers that I'm going to rent a larger space to have more room for products because this place is too small. People are coming all the way from Jbeil [north of Beirut], south, north and all around Beirut because of the lower prices.

"There are things that we can't import cause they're too expensive," he explained, "so we try our best to find cheaper alternatives and sometimes we have to forget about making any profit and just sell it for its capital price. A lot of my oil brands I don't make any profit from. Usually the teas I make around a 500 lira (£0.25) profit."

The rise in costs has caused many people to demand more products to be made in Lebanon so that there can be cheaper alternatives to the more expensive, imported goods.

"That's the issue," Hanna stated. "We have a few products that are actually made here [in Lebanon], but it's not much. They [the government] didn't give us a chance to become an industrial country where we actually consume what we produce. Our entire economy is based on getting stuff from the outside, on importing. Not exporting which is sad."

Despite these calls, Al-Akkaoui explained that it could take time for that to happen as well as the desperate need for changes to Lebanon's law to make it easier for producers and business to operate in the country.

"We need to wait three to five years for everything to stabilise again if we do the right policy decisions," he explained.

When asked, Hanna explained that he is trying to do what little he can to help influence a better change for Lebanon and that he hopes if others do the same, then it could potentially slowly help to move the country forward.

"I would like to see a change," he said. "We're trying to be the change that we want to see. Look at what I'm doing. I'm getting my dough from several shops because I think that these small acts are the ones that make a change.

"If someone else did the same, we are indirectly boosting the economy. We're making the wheel turn at least a little bit and that's what we're trying to do. Hopefully we'll become the change that we want to see because we just don't care about them [the politicians]. They live in their own dreams. They have their money. They have their cars. They have their lives and we have ours."

Shehaytli also sees his shop as a way of helping people and feels that his work is important to help his country.

"A lot of people and shopkeepers are greedy," Shehaytli stated. "Even though it's understandable that big supermarkets have fees and salaries that they need to pay, but small shops like us don't."

Despite their efforts, the economy continues to worsen with Al-Akkaoui comparing Lebanon's current situation to the Great Depression.

|

|

"Poverty is going to rise," he explained. "We need social collaboration, we need to help each other out because we are diving completely straight down as fast as we can. We're in a recession right now, one that is worse than the US recession of 2008. It's more like the Great Depression of the early 1900s."

In order to solve the crisis, the government needs to create a plan to move forward, but after decades of corruption and failed policy, there is little public trust in the new government formed by Prime Minister Hassan Diab.

"We need to build a new social contract that shows that we are taking people's concerns seriously," Bejjani said. "Even if this government tries, they will be judged extremely harshly due to the lack in trust and their often failed policies. When people go hungry, I don't think that they will stay calm."

Due to the deteriorating situation, many Lebanese are looking for opportunities abroad so that they can leave. However, Hanna said that he refuses to do this because he views this as a last chance for people to change the country.

"I encourage people to give it a last shot and I believe we can make it," Hanna said.

"We can get rid of all of them [the politicians] and make them pay for the mistakes that they made and move forward. We have to. If we don't do it, then who is going to?"

Nicholas Frakes is a freelance journalist who reports from London, the Middle East and North Africa.

Follow him on Twitter: @nicfrakesjourno

The New Arab is covering the protests day by day, offering news updates, analysis, commentary and much more. Click on Special Contents page below and follow this regularly updated section for the latest on Lebanon's uprising:

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News