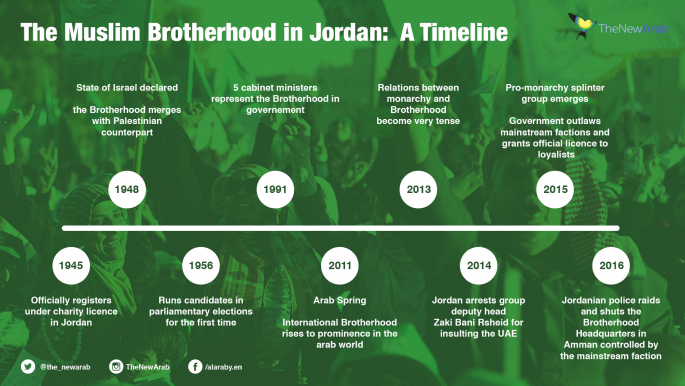

The gradual weakening of the Muslim Brotherhood in Jordan

Tensions between the government and the Brotherhood have escalated since the closure, despite the latter's break with its Egyptian counterpart. The future of the Jordanian MB remains uncertain.

What triggered the closure?

In 2014 the Jordanian government issued a new law requiring all organisations and political parties to register or renew their licenses.

Following this development, an offshoot group of the MB, called the Muslim Brotherhood Society [MBS], defected from the larger MB movement and acquired a license.

The official Jordanian branch of the MB, however, lost its registration after the new government requirements were instated. Moreover, the government prevented the MB from holding internal elections and its 70th anniversary rally.

The Jordanian MB responded by citing two previous legal registrations: one in 1946 under the era of King Talal and again in 1953 under King Hussein. They also claim the government is using this new licensing law as an excuse to besiege the Brotherhood.

Does the recent clash between the government and the MB mean that the rules of the game have changed? Is Jordan heading toward the total exclusion of the MB to conform with trends in the region? And why does it seem that whenever the relationship between the government and the MB worsens, divisions within the MB also worsen?

MB paralysis

Before looking more closely at the recent escalation between the Jordanian regime and the Brotherhood, we must first analyse the profound changes that have gradually affected the MB over the past decade.

The MB has always possessed the ability to maintain organisational unity, despite ideological differences.

|

What distinguishes the group in Jordan from others in the region is that it has not relied on a charismatic leader. Instead, it has depended on preachers, religious activists, trade unionists, and a mixture of rising professional figures primarily from the middle class. |  |

What distinguishes the group in Jordan from others in the region is that it has not relied on a charismatic leader.

Instead, it has depended on preachers, religious activists, trade unionists, and a mixture of rising professional figures primarily from the middle class.

Although the political mechanisms of action began to change in the early 1990s, the group was still able to spread its influence steadily throughout the political and social fields.

This, along with its capacity to maintain unity, led to an excess of self-confidence and made the group oblivious to the changes that impacted Jordan's social structure, including the beginning of privatisation and the decline of the public sector.

The group did not move to change its tactics, rhetoric, or structure. It also failed to recruit talent from youth groups and trade unions, instead spending effort on charity work.

The group continued to act simultaneously as a religious movement concerned with the reform of the individual in accordance with Islamic vision and as a political party subject to the changing rules of politics.

This duality strained the group and led to its inability to achieve progress in either of the two fields.

Internal divisions

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

As the Jordanian MB grew more sceptical of the political process, the group began to question what should be done next.

Differences deepened within the MB and split both the "doves" - who are more open - and the "hawks" - who are more rigid and closed - into several groups.

Intellectual divisions were not the only reason for differences within the MB. Signs of a split along ethnic lines between Jordanians and Jordanians of Palestinian origin became apparent within the party.

This left many members disappointed, because they felt the group had previously been far removed from racism or ethnic divisions.

As differences within the MB expanded, isolation of the group also increased until it became so paralyzed and weak that it was unable to function.

With every clash with the Jordanian regime, the Brotherhood became more scattered.

A leading analyst on the Islamist movement, Hossam Tamam, said, "[The MB] knows what it doesn't want but doesn't know what it does want."

Religious trends have also changed in the region, and individual religious experience is no longer tied to Islamist groups.

New religious groups are emerging that believe Islamist-minded individuals should concentrate on social and moral issues rather than political ones.

|

New religious groups are emerging that believe Islamist-minded individuals should concentrate on social and moral issues rather than political ones. |  |

The Jordanian government is fully aware of the group's vulnerability and considered splits within the MB as a golden opportunity to weaken and push it toward further isolation.

Yet the Jordanian government has not sought to exclude the Muslim Brotherhood entirely from the political scene, nor has it launched mass arrests of members - as has occurred elsewhere in the region - and it has allowed the group to set up economic and religious institutions.

Prior regime support

The MB was previously allied with the Jordanian regime. When officers in the Jordanian army attempted a coup in 1957, the Brotherhood mobilised people on the ground against the government, which was later dissolved by the king.

King Hussein then prohibited all political parties, with the exception of the Muslim Brotherhood, and declared martial law in 1957.

When democratic life returned in 1989, the Muslim Brotherhood won 22 seats in the newly elected parliament and controlled the legislature for three consecutive terms.

|

The regime recruited the Islamist movement to gain more legitimacy, because the MB received hundreds of thousands of votes from Jordanians, particularly those of Palestinian origin. |  |

The regime recruited the Islamist movement to gain more legitimacy, because the MB received hundreds of thousands of votes from Jordanians, particularly those of Palestinian origin.

While the MB movement was banned throughout much of the Arab world, the MB in Jordan operated fairly freely but with some limitations.

The Jordanian government was alarmed by the MB's opposition to the Wadi Araba agreement in 1994 between Jordan and Israel, and since then authorities have gradually increased the pressure on the group.

When King Abdullah came to power in 1999, the movement's relationship with the royal palace weakened.

With the outbreak of the Arab Spring in 2010, the Brotherhood actively participated in demonstrations that called for more reforms, but it did not call for regime change.

The Jordanian regime was not happy with the MB, even though the group demanded constitutional reforms to establish an elected parliamentary government with broad powers rather than a partial reduction of the king's power.

|

The Jordanian government was alarmed by the MB's opposition to the Wadi Araba agreement in 1994 between Jordan and Israel, and since then authorities have gradually increased the pressure on the group. |  |

With the decline of the power of the streets following the Arab Spring and the military coup against Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi in 2013, a wave of counter-revolutions in Arab countries began and called for the MB to depart from the political scene once and for all.

What happens next

Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates [UAE], and Egypt have all banned the Muslim Brotherhood and added the movement to lists of designated terrorist groups.

Meanwhile, the Jordanian regime seeks to gain support from the MBS in order to further weaken the MB.

It is unlikely that authorities will seek to follow Egypt or the UAE's lead with a total ban of the MB; it is more likely that the regime will continue to gently pressure the MB, ensuring it remains in a constant state of weakness.

Such policies, however, could have the opposite intended effect of further mobilising extremist elements because many have lost hope in the political process.

A copy of this report first appeared in the June 2016 issue of the Wilson Center's Middle East program.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News