Blast-proof tourism: Egypt builds a wall around Sharm el-Sheikh to 'keep out terrorists and Bedouins'

Those days are now long gone.

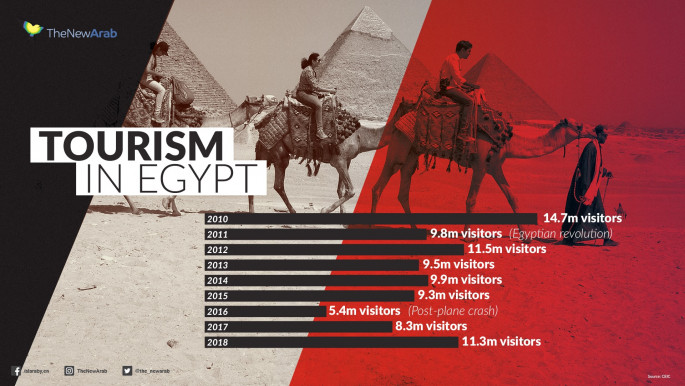

The sun remains high in the sky, but the catastrophic downing of a Russian airliner four years ago in an attack claimed by the Islamic State [IS] group's Sinai affiliate sent tourist numbers plummeting.

Since the 2015 deaths of all 225 people on board, the lurking threat of terrorism and Egypt's abysmal security record has transformed the jewel of Egypt's tourism crown into a ghost of its former self.

The coastal city's recovery has not been aided by Russian and British bans on direct flights to its airport, and it remains to be seen whether last week's announcement by the UK FCO overturning the ban will be a turning point for the popular destination.

|

|

Now, desperate for foreign cash, the embattled Egyptian regime has cooked up a plan to revive this tourist mecca.

The catch? It involves building a hybrid concrete wall and metallic fence around the city to reassure reluctant tourists at the expense of local residents, especially the peninsula's native Bedouin population.

But according to experts interviewed by The New Arab, the costly project will likely be ineffective and could even make the security situation worse.

Fury over allegations of corruption surrounding the construction of expensive and unnecessary presidential palaces drove thousands of austerity-fatigued Egyptians to protest against the brutal police state of President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi last month.

But luxury construction projects aren't the only white elephant calling Sisi's government into question and residents of Sharm el-Sheikh, hundreds of kilometres away from the capital, are also quietly wondering if a controversial wall built to shield it from security threats isn't just a waste of public funds.

News of the Sharm el-Sheikh wall first emerged on the global news agenda in February this year, when the Guardian revealed the South Sinai governorate had begun the construction of a six-metre-high concrete barrier surrounding the city, cutting it off from the expanse of the surrounding Sinai desert.

The construction of the wall has been justified on security grounds but the authorities have also claimed it is a "beautification" measure to block rubbish from entering the sea.

Either way, it's clear the officials believe whatever – or rather, whoever – is stopping Sharm el-Sheikh from being safe, clean and beautiful lies beyond the wall, in the Sinai desert.

|

Either way, it's clear the officials believe whatever – or rather, whoever – is stopping Sharm el-Sheikh from being safe, clean and beautiful lies beyond the wall, in the Sinai desert |  |

Egypt's North Sinai province is home to the country's IS affiliate, Wilayat Sinai, and other extremist militants who have been engaged in a bloody insurgency against the state since 2011.

When local militants intensified their attacks against government forces and civilian targets after Sisi's rise to power in a 2013 coup, the regime escalated its counter-insurgency in a scorched earth campaign that has seen Egypt accused of "serious and widespread abuses" against civilians, some of which Human Rights Watch has described as tantamount to war crimes.

The military's deadly campaign has seen civilians subjected to mass arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances and torture, transforming the lives of thousands of residents into a living hell.

Already earmarked by the state as a security threat for their perceived involvement in a series of extremist attacks two decades ago, the long-disenfranchised Bedouin population of the Sinai are now subjected to what amounts to collective punishment.

Read more: Chaos by design: How a violent and lawless Sinai benefits Sisi

Egypt began the construction of the six-metre high "security fence" last year, surrounding the airport at Al-Arish, capital of the North Sinai governorate, and another wall at the city's southern reaches, Mada Masr and the Associated Press reported.

But there is a vast gulf between Al-Arish and Sharm el-Sheikh. With the insurgency largely contained to the peninsula's north, some residents of the Red Sea resort town are wondering why the state has invested so much in the security perimeter.

The New Arab was not able to independently verify the exact scale of the Sharm el-Sheikh wall, but pictures obtained from local residents suggest its height is somewhere between that of the Berlin Wall and Israel's so-called "separation barrier".

The purpose of the barrier – reportedly up to six metres high in certain spots and as much as 37 kilometres (23 miles) long – appears to be the creation of a contained, sanitised Sharm el-Sheikh secure from the illusion of threat.

In a not-so-subtle nod to the city's moniker "The City of Peace" – given to Sharm el-Sheikh for its hosting of several major peace negotiations in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict – it is emblazoned with gigantic peace signs every 50 metres or so, pictures obtained by The New Arab show.

For every two peace signs, of course, there is a camera.

|

|

| The wall deviates from the course of the road in order to include Sharm el-Sheikh's electricity station within the city limits [The New Arab] |

|

|

| A section of the Sharm el-Sheikh wall [The New Arab] |

|

|

| The construction is a mix of concrete barriers and razor-wire fence [The New Arab] |

Following the course of existing roads in the province, the wall extends from a security checkpoint north of the city for travellers on the road to Dahab down to another checkpoint in the city's southwest on the road to El Tor.

In interviews with the press, South Sinai Governor Khaled Fouda has attempted to muddy the waters by stressing the construction is not technically a "wall" but a mix of concrete barriers and razor-wire fence.

Some Egyptian commentators have echoed this narrative, a symptom of restricted access for journalists and researchers that has meant the construction has left a minute online footprint lacking precise blueprints.

"The idea that the state is building a wall around Sharm el-Sheikh is not accurate," Egyptian journalist and Sinai security expert Mohannad Sabry told The New Arab. "There have been bits and pieces of concrete barriers but this does not represent a wall."

It is indeed unusual that so few details about the wall have emerged online. Sisi's regime, widely accused of human rights violations, including restrictions on freedom of speech, may be partly to blame.

But, amid a series of relatively low-key discussions on social media in recent months, The New Arab found that, while residents' views on the wall are mixed, some are worried over the development which has drawn comparisons to Israel's "separation barrier" in the occupied West Bank.

When one Facebook user posted a photograph of the wall partly under construction in March – jokingly calling it the "Great wall of Sharm el-Sheikh" – one of the user's friends replied: "It reminds me of the wall in Palestine."

|

It reminds me of the wall in Palestine |  |

Some residents of the Red Sea city believe the wall will serve as a positive development to revive Sharm el-Sheikh's ailing tourism industry.

When one Facebook user posted an image of a fully constructed section of concrete wall in March, they mused: "If the Sharm el-Sheikh wall will result in the return of British and Russian tourism, then I agree with it... If not, all of this will have been for nothing," they added.

A friend rebutted: "This is a massive mistake, of course."

Others have questioned whether the presence of a large concrete barrier will make European tourists feel safe at all. "Tourists will really feel they're in security and luxury in this luxurious town of walls," joked one Facebook user.

What is clear is that the issue is a sensitive one, lending credence to the reports of the wall's large scale.

When The New Arab contacted a Sharm el-Sheikh resident who had publicly discussed the wall for comment, the individual accused the foreign media of attempting to peek at Egypt's "laundry" and threatened to report The New Arab's reporter to the security services.

Ruwaisat, a village that includes both residential and industrial areas, is now cut off from the rest of the city in a move that threatens to exclude its residents from the fruits of fresh development, a resident of the area told The New Arab on condition of anonymity.

The New Arab confirmed the segregation of the area by analysing both the trajectory of the wall and social media posts from local residents.

The village is known for its "slums" – slapdash informal housing largely erected by displaced Bedouin – but it is also home to labourers imported from Upper Egypt to work in the city's tourist resorts, as well as foreign residents eschewing "compound living" elsewhere in Sharm el-Sheikh.

Earlier this year, Governor Fouda promised to rid South Sinai of such unpermitted housing, declaring that there would be "no slums" in the region by 2020, and said he hoped to replace the "dangerous slum area" with upscale luxury housing.

That "dangerous" reputation stems from Ruwaisat's perceived status as the prime location for Sharm el-Sheikh residents to buy illegal drugs.

|

|

| Some residents believe the wall will serve as a positive development [The New Arab] |

|

|

| Concrete barriers meet fencing on Sharm el-Sheikh's wall [The New Arab] |

Some residents are on board with the wall for the same reasons. "This is right, to protect the town from smuggling and drugs," one Facebook user claimed in a comment on a local news page in June.

Drug smuggling in the Sinai, according to Joshua Goodman, Assistant Professor at St. Lawrence University and author of a book on the South Sinai Bedouin, has a "long and fairly storied history" spanning decades, a trade that is intricately tied to local Bedouin tribes.

Though not as significant as in the past, drug smuggling remains a key source of income for Bedouin communities, particularly inland tribes who have limited access to the tourist industry.

"When you're travelling into Sinai, one of the things that strikes you is that the Egyptians really just control the roads and the towns on the coast," Goodman told The New Arab.

"Once you move inland a bit, their presence disappears almost entirely. The old trade routes are completely open to Bedouins, and they know the safe havens where they can cultivate, and the routes where they can move drugs in order to get around government checkpoints."

Despite suffering from historic disenfranchisement like the North Sinai Bedouin – forcibly displaced to enable new developments and passed over for resort jobs in favour of transplants from Upper Egypt – the local population of the more-developed South Sinai have "almost categorically" opposed involvement in violence, Goodman said.

The South Sinai Bedouin have nonetheless been classified as a security risk by the state, subject to enhanced scrutiny at checkpoints and restrictions on movement for decades.

Deemed undesirable, it seems their very presence would be enough to disturb the state's narrative of a safe and secure Sharm el-Sheikh open to tourists once more.

When one Twitter user wrote in July that the reason for the exclusion of Ruwaisat was to control the "infiltration of Bedouin from the desert", another questioned: "Did the Bedouin cause the security disruption in Sharm el-Sheikh? When was the last terrorist incident?

"What is the cost of this wall and the real reason for its construction? Considering the current state of this country, I think it's a waste of public funds."

This is not the first time the Egyptian government has had "similar plans to build a wall around the tourist areas in South Sinai", Allison McManus, Research Director at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy (TIMEP), told The New Arab.

Plans for a wall sequestering the city's heavily touristed coastal strip from the rest of the province were floated in 2005 following a coordinated triple bomb attack on hotels and a market that year, Goodmain explained.

The extremist attack killed 88 people and led to a sweeping security crackdown in which local Bedouin communities were subjected to mass arrest for their alleged aid to the bombings.

|

Hidden behind the city walls, the residents of Ruwaisat face a future cut off from the fruits of any future development in Sharm el-Sheikh |  |

"There were members of northern tribes who had been absorbed into some of the Islamist groups that were complicit in the bombings," said Goodman.

"The Egyptian state's response to the bombings was a fairly widespread crackdown on the tribes. The Egyptian government didn't really make a very nuanced distinction between the tribes in the north and the tribes in the south, even though the social geography is completely different."

The plans did not come to full fruition, but the regime did construct a short concrete barrier following a similar route as the new wall.

"They were trying to stop anybody coming off road from the desert into Sharm," a resident of Ruwaisat told The New Arab on condition of anonymity. "You could climb over the wall easily but no car could come through."

It's also not the first time the village itself has been pinpointed as undesirable by the state.

"It's always been the government's policy to separate Sharm el-Sheikh from Ruwaisat," Sabry, the Sinai security expert, explained.

"The government thinks it is a shame to have those poor locals around the touristy, fancy Sharm el-Sheikh, and it's a shame to have the president sitting at the palace in Sharm el-Sheikh playing golf and a couple of kilometres away we have the riff-raff."

|

|

Hidden behind the city walls, the residents of Ruwaisat face a future cut off from the fruits of any future development in Sharm el-Sheikh, said a resident of the area.

Stringent security measures already restrict access to the city to those with a job, residence or hotel reservation. Residents of the village face an uncertain future; if their job is outside of the wall, it is unclear whether Ruwaisat locals will be able to travel into the city.

While the route to Ruwaisat through Sharm el-Sheikh's "peace wall" is easy enough, getting out of the area and into the city is another matter entirely – a convoluted route that has provoked complaints from residents on social media.

Residents must drive a route that takes about ten minutes before reaching a newly constructed checkpoint area – two buildings with entrances large enough to accommodate a truck, according to The New Arab's source. Access to the city on foot is not permitted.

In those customs-like checkpoint areas are large new x-ray machines. While not yet operational, Ruwaisat residents are reportedly worried that they will have to be exposed to radiation every day when travelling into the city.

"There's a sign next to the x-ray machine that says pregnant women aren't allowed to go through it, so people are nervous about what levels of x-ray radiation they are going to be experiencing," the Ruwaisat resident explained.

Read more: Sisi's Sinai operation is counter-democracy, not counter-terrorist

The aim of such checkpoints, McManus explained, is to increase security in the "popular tourist areas".

It is unclear why, then, the machines have been installed at the Ruwaisat checkpoint but not in the Dahab, Sharm el-Sheikh and Safari checkpoints commonly frequented by tourists.

The conflict in the Sinai has largely been restricted to the north of the peninsula, but that's not to say there is no threat of danger in the South Sinai.

|

|

Militants have staged attacks in both central and south Sinai in recent years – most notably the IS-claimed downing of the Russian airliner just four years ago.

"There is a threat," stated Sabry. "Is there a way to calculate how high or low the threat is?

"It's quite impossible given the complete lack of access, the ambiguity of the situation, [and] the fact that IS doesn't have a set pattern of attacks," Sabry explained.

Although the Egyptian journalist is skeptical of the size and scale of the Sharm el-Sheikh wall, he pointed to the perception of such a security threat and the nature of Sisi's regime were push factors behind the development of any new security measures.

|

There's a crazy paranoid regime... They're crazy enough to do anything |  |

"There's a crazy paranoid regime [here]," he said. "They're crazy enough to do anything."

But there is little to "suggest that the creation of such a wall will actually make the area more secure in any meaningful way," said McManus.

Indeed, such a wall could even be a target for extremist attacks. At least seven workers have been killed in suspected IS attacks in Al-Arish after working on the construction of the city's two security walls.

While the wall could improve security by acting as a deterrent, Sharm el-Sheikh could also prove "too ripe a target" for militants who have staged attacks on tourists in the past, said Goodman.

"I have real questions about whether this wall would be able to stop a disciplined and motivated militant group," he said. "Keep in mind that they can also come in by sea."

Rather than a measure towards truly improved security, McManus said, the wall is "in line with the military's approach to security as control of an area, population, or mobility".

In other words, she said, the wall is more of a "symbolic measure than a practical one" – a visual reminder of the military's presence in and supremacy over the area.

The wall, then, has a dual purpose: from the inside, to create the image of a safe and secure Sharm el-Sheikh, and from the outside, to remind those the government does not want inside Sharm el-Sheikh that the city belongs to the military and its interests.

It wouldn't be the first time Sisi has been accused of putting the military and its interests before those of Sinai locals.

Last month's protests against the president were sparked by a series of viral videos released by Mohamed Ali, a former government contractor who alleged the president and his military appropriated millions in public funds to build luxurious palaces and villas while at least a third of Egyptians live in poverty.

At the same time, Sinai activist Massaad Abu Fager released his own series of videos on social media, unleashing a series of scandalous allegations and ultimately endorsing Ali's call for widespread demonstrations against the regime.

He alleged the military's fight in the Sinai was not genuine, but rather linked to corruption and a desire to supplant the peninsula's native inhabitants.

The military claims part of its mission is to fight against arms and drug smuggling routes into the besieged Gaza Strip. Abu Fager alleged Mahmoud al-Sisi, son of the president and a senior intelligence official, was in fact at the helm of the lucrative smuggling business.

The activist also claimed Egypt's fight against terrorism in the Sinai peninsula could have been solved years ago with the aid of locals – help the government allegedly refused. Abu Fager claims that many of the more than 3,000 militants the military claims to have killed in the conflict are in fact civilians, caught up in a conflict manufactured and perpetuated by the state.

|

Under the name of fighting terrorism, they demolish people's homes and commit ethnic cleansing |  |

"It's impossible to fight only 1,000 fighters in seven years," he said. "The Egyptian army is not fighting terrorism in Sinai.

"Under the name of fighting terrorism, they demolish people's homes and commit ethnic cleansing," claimed Abu Fager. He went on to allege that this "ethnic cleansing" was being committed in the interests of Israel's Prime Minister Binyamin Netanyahu and the US-crafted "Deal of the Century" peace plan which some have alleged aims to craft a national homeland for Palestinians in the Sinai.

In areas such as North Sinai's Rafah and Cairo's Warraq Island, where Egyptians have had "the misfortune to physically occupy spaces desired by the state", citizens have faced a pattern of forced displacement and demolitions of homes and businesses, said McManus.

Citizens are left with "little to no recourse" to contest the loss of their homes and even livelihoods, the researcher explained.

"Already over the past years we have seen unclear or seemingly conflicting laws and policies regarding land ownership in Sinai that allow the state to dispossess Bedouin from inherited land they've occupied for generations," said McManus.

"It's indicative of an approach to development that prioritises attracting foreign capital at the expense of Egyptian citizens."

Critics worry that increasingly extreme security measures such as Sharm el-Sheikh's wall could further alienate local Bedouin communities from the state and the fruits of development, a long-lasting phenomenon that some say fomented violence in the North Sinai.

Tourism represents the sole reliable source of income for the South Sinai Bedouin, Goodman explained. With the industry already weakened in 2015, the wall represents another challenge for the community.

Increased security measures and the risk – perceived or real – of terrorism will "hit the community hard" and harder than others living there, as, unlike Egyptians from Upper Egypt who the state and resorts prefer to employ in the tourism industry, the Bedouin do not have the option of leaving the Sinai.

While Sisi's wall could provide the desired result – a sanitised picture of Sharm el-Sheikh free from drugs, slum housing and poverty – it could also backfire by providing a clear target for militants or failing to persuade tourists of the city's security.

By further policing the movement of the local Bedouin and sending a clear message that they are not wanted in Sisi's Sinai, the wall could also fatally uproot the community.

The clearest threat to the Bedouin community is economic, but some say the further the state pushes its citizens away, the closer it comes to more violence.

"I've got a feeling that it's like when someone is born," said The New Arab's source in Ruwaisat. "You cut off the umbilical cord and that little bit just shrivels and dies, and falls off.

"If you cut something off like that, it can't survive."

Mel Plant is a journalist at The New Arab.

Follow her on Twitter: @meleppo

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News