'Now we await our fate': Displaced Yazidis fear loss of land in Syria

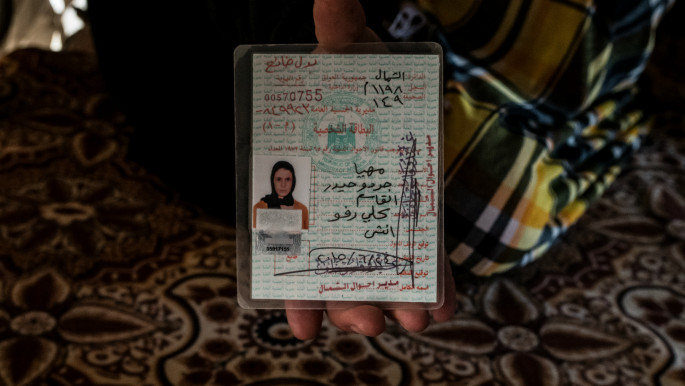

Among the hundreds of thousands uprooted by the Turkish offensive in northeastern Syria are Yazidis who fear the ongoing violence puts their already shrinking minority at risk of extinction.

"We ran out out of the house without even eating or changing clothes," said Khader Hamo Khabour. "We left in the middle of the night for fear that they would kill us as happened with our people in Sinjar."

The day after Turkey launched its military operation in northeast Syria, Khabour and his family packed up and left their village near the border town of Ras Al-Ain. He sent his three teenage children to northern Iraq to live with friends of the family. Khabour, his wife and 10-year-old daughter stayed behind, first fleeing south to Tall Tamr and then on to the Hasakeh province.

They found refuge at Yazidi House, a local organisation that serves Yazidis in the region, and is providing water, food and mattresses to displaced families.

"I know nothing about my house and land. Is it destroyed? Did they steal from it?" Khabour said. "Now, we await our fate."

In the weeks since Turkey launched its military incursion into northeastern Syria following the sudden withdrawal of US troops from the region, the United Nations estimates nearly 180,000 Syrians have fled their homes.

The UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, a war monitor, puts the number of displaced at more than 300,000.

Despite an agreement reached between Ankara and Moscow to push back Kurdish YPG fighters from the border in exchange for Turkey halting its incursion, the situation remains volatile. This week the Syrian army reportedly clashed with Turkey-backed forces in the Ras al-Ain countryside.

Since the start of Turkey's offensive on October 9, local activists say more than two dozen Yazidi villages have been nearly deserted.

|

The Yazidis are always doubly exposed to the effects of war because they live in Kurdish areas and are not of the Muslim religion |  |

A majority of the displaced have fled south, including to Hasakeh city, which according to UNICEF, has run out of capacity to absorb any more fleeing Syrians. Others, like Khabour's children, have paid smugglers to cross the border into Iraqi Kurdistan, which now hosts more than 12,000 Syrian refugees from this latest wave of violence.

|

|

| Read also: 'Their wounds must be acknowledged': What does the future hold for Yazidis who survived IS? |

Ziyad Rustam, a staff member with Yazidi House, says his organisation has been placing displaced Yazidi families in abandoned houses and providing them with basic necessities. But as with other aid organisations in the region, Yazidi House is stretched thin.

"We collected some donations from Yazidis in our region who have not been displaced, but of course, it doesn't make much of a difference," he said. "We certainly need more help."

Turkey says its aim is to clear Kurdish fighters from its southern border and in their place, settle up to three million Syrian refugees currently living in Turkey.

But Yazidi activists say members of their community are the unintended victims of an ethnic cleansing campaign targeting the Kurds.

"The Yazidis are always doubly exposed to the effects of war because they live in Kurdish areas and are not of the Muslim religion," said Rustam.

Earlier this month, a letter signed by nearly 30 Yazidi leaders warned "the current events in northeastern Syria, if not halted, will annihilate Yazidis from their ancestral homeland in Syria."

|

The current events in northeastern Syria, if not halted, will annihilate Yazidis from their ancestral homeland in Syria |  |

This is far from the first time members of this ethno-religious minority have faced marginalisation for their religious beliefs, which combine elements of Christianity, Zoroastrianism and Islam, and whose central figure is a fallen angel.

|

|

The Yazidis claim to have been victim to 72 genocides during their long history. In recent years, hundreds died in car bombings carried out by al-Qaeda in Iraq, the predecessor of the Islamic State group [IS], in 2007.

Then in August 2014, IS stormed the Yazidis' ancestral homeland of Sinjar in northern Iraq, denouncing the members of this ancient religion as devil worshippers.

In what the United Nations now calls a genocide, thousands of Yazidis were killed and their bodies thrown into mass graves. The terrorist group also kidnapped some 7,000 women and children and forced them into sexual slavery.

In January 2019, Yazidi activists warned that a looming Turkish offensive would endanger their small community and that of other minorities in northeastern Syria.

The year before, Turkey launched a two-month-long offensive into the predominantly Kurdish town of Afrin. International rights groups documented the wide-scale persecution of Kurds, as well as Yazidis, by Turkish-backed armed groups.

According to the United Nations, rebel groups destroyed Yazidi temples and holy sites. Residents reported that the fighters threatened to kill some Yazidis who did not convert to Islam.

"The same thing is happening now," said Murad Ismael, co-founder and executive director of Yazidi advocacy group, Yazda.

This month, soldiers fighting under the banner of the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army have been widely accused of human rights violations and war crimes against civilians in the northeast. In one incident, well-known Kurdish politician Hevrin Khalaf was brutally executed on camera by fighters from the Turkey-backed Ahrar al-Sharqiya militant group.

Turkish officials deny that war crimes were committed by its affiliated rebel groups.

Having watched what happened to Iraq's Yazidis at the hands of IS, Ismael worries those in Syria are at risk of losing their homeland too.

Although it was liberated from IS five years ago, only a quarter of Sinjar's original population has returned due to a lack of basic services and security.

"I think a lot of these communities – Yazidis, Christians, Assyrians, Shabaks – they're very tied to their homeland," said Ismael. "Once their homeland is taken, it's very questionable whether that culture will continue or not."

Elizabeth Hagedorn is a freelance journalist focusing on migration and conflict with bylines in The Guardian, Middle East Eye and Public Radio International.

Follow her on Twitter: @ElizHagedorn

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News