Revolt Against the Sun: The Selected Poetry of Nazik al-Mala'ika

But she also plainly states her reason for her translation. "To read Malāʾikah in English translation was to go hunting through anthologies of Arab women's poetry, seeking out a few poems here and there. By contrast, nearly every collection Maḥmūd Darwīsh ever wrote has been published as its own volume in English, and readers can peruse several books of Adūnīs' poetry in English too."

And it is with this poignant reflection upon the neglect and dismissal - along clear gender lines - of one of the most significant writers of the 20th century that Drumsta introduces her bilingual collection.

The "ghettoisation" of women in anthologies is not new, and certainly not for writers from the Arab world. "Women poets like Malāʾikah and her contemporaries Fadwā Ṭūqān, Lamīʿah ʿAbbās ʿAmārah, Mayy Ṣāyigh, and many others have for years been relegated to the realm of anthologies," Drumsta writes. Yet, it is difficult to imagine how one of the pioneers of free verse in Arabic languished in the shadows of Arab modernism.

|

|

| Read more from TNA's Book Club: The best books by Arab authors in 2020 |

While the book blurb claims the collection charts Mala'ika's transformation from a lyrical romantic poet to a politically committed nationalist poet, it is really the poem that shares the title of the collection that wholly reflects this spectrum.

In "Revolt Against the Sun", one of the earlier poems from her 1947 collection Night Lover, Mala'ika transforms sadness into a means for action, delivered in confessional form before the sun.

"She stood before the sun, screaming out loud: / Oh Sun, my rebel's heart is just like you: / while young, it washed away much of my life … / This sadness is the form of my revolt, / to which the gods bear witness every night."

The rebelliousness and revolt offered to the sun are later withdrawn, as it proves disloyal and fickle, and so the speaker plans to build an alternative world to the one she shares with the sun: "I will shatter the idol that I built … / I'll build a heaven out of hidden hopes / And live without your luminosity. / We dreamers know we hold within our souls / divine secrets, a lost eternity."

While the sentimental tone and the ideals of the unity of wo/man and nature gesture toward a romanticism that Mala'ika espoused early on, it is really the political themes of rebelliousness and revolt that override the sentimentality and evoke the possibility of building an alternative world.

And, indeed, as Drumsta points out in an earlier article, it is no accident that Mala'ika used political terminology, like thawra and tamarrud, revolution and rebellion or insurrection, respectively. While Drumsta's translation style is lean and smooth, it does not detract from the sentimentality undergirding "Revolt Against the Sun", or Mala'ika's other early Romantic poems.

|

Emily Drumsta's translation reinforces the significance of the Iraqi poet, recounting her large oeuvre and declaring her one of the most significant writers of the twentieth century |  |

Spanning from the 1940s until the 1970s and reflecting the arc from romantic to politically committed poetry, the collection is organised chronologically, with a few poems selected from each Mala'ika book, including Night Lover (1947), Shrapnel and Ash (1949), At the Bottom of the Wave (1957), The Moon Tree (1968), For Prayer and Revolution (1978), The Sea Changes Its Colors (1977).

From Mala'ika's early work (Shrapnel and Ash, 1949), one poem has recently been retrieved by contemporary writers reflecting on Covid-19. In the poem "Cholera", she captures the uncertainty, disorientation, and fear surrounding the spread of disease wherein darkness overtakes a landscape marked only by sounds of misery:

"In the night / listen to echoed moans as they fall / in the depths of the dark, in the still, on the dead / voices rise, voices clash / sadness flows, catches fire / echoed sighs, stuttered cries / every heart boils with heat / silent hut wracked with sobs / spirits scream through the dark everywhere / voices weep everywhere / this is what death has done / they are dead, they are dead, they are dead / let the screaming Nile cry over what death has done."

|

|

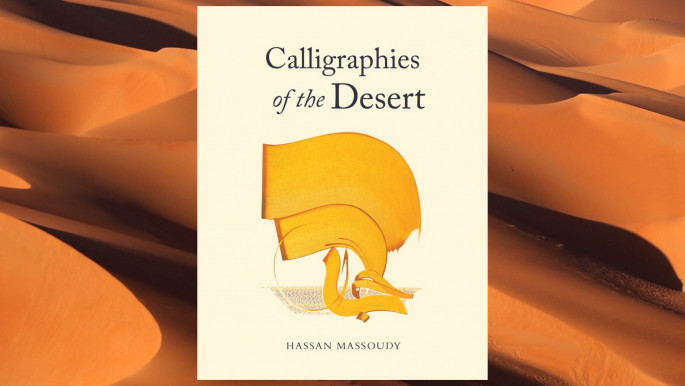

| Read more from TNA's Book Club: Calligraphies of the Desert by Hassan Massoudy |

Contemporary Arab writers have recollected the poem to point to the significance of giving voice to mourning under a plague, even though Mala'ika's own voice was one empathic to the suffering that many Egyptians underwent during the cholera epidemic.

While it is clear that emotion and sentiment power Mala'ika's poetry, her transformation into a politically committed poet did not dampen the fervour of her voice, or as Drumsta explains, "she married overflowing emotion with political occasion-marking."

In other words, Mala'ika's poetry reflected the ways the political is personal. From her 1968 collection, nationalist poems warn against foreign influence, especially after the bloody path "to nourish liberation". In 'Greetings to the Iraqi Republic', she cautions, "The market's open, rose of ours – beware its cruel jaws / stained with Zionist vengeance sought with American claws".

In 'A Song for the Arab Ruins', she mourns: "My Arab friend, they're foreignizing all the old abodes …/ Foreign footsteps now desecrate the plains where oryx roamed /and 'Tel Aviv' is written in the sands / of Bakr, Waʾil, and Nizar's old lands." In 'Three Communist Songs', a wide gulf separates Arab identity and Communist affiliation, as Mala'ika appears to jeer behind the words "Beware, comrade – the rose has religion / it smells Arab."

While Drumsta's translation style is economical, she remains guided by the principle to re-create the original text in English without distorting its essential meaning. This bilingual collection presents the English translation on one page and the Arabic original on the next, so it might be useful to think of it not only as a text for those interested in modern Arabic poetry and Mala'ika, but also as a resource for language and literacy development of advanced Arabic students.

It goes without saying that this collection is gratefully welcomed, considering not only the "ghettoisation" of Arab women writers in translation, but more broadly the dearth of Arabic literature in English as a whole.

Nahrain Al-Mousawi is a writer currently based in Morocco.

Follow her on Twitter: @NahrainAM

The New Arab Book Club: Click on our Special Contents tab to read more book reviews and interviews with authors:

|

|

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News