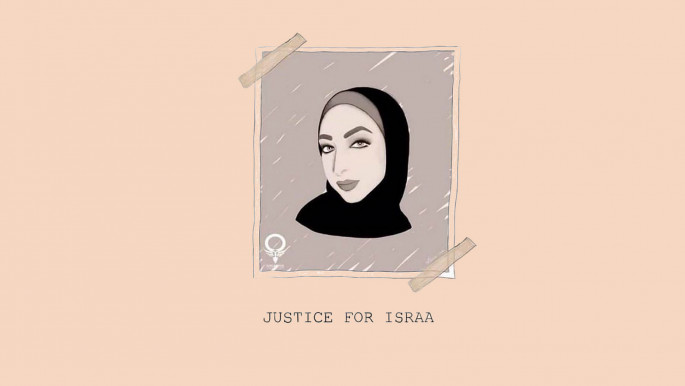

Amid outrage over Israa Ghrayeb, Palestinian film festival says 'No Means No'

Last month, cries of "We are Israa" flooded Palestinian streets. In light of the brutal murder of 21-year-old makeup artist Israa Ghrayeb by her family, anger is growing over gender-based violence in Palestine. And that mood of resistance is now seeping into the state's art scene.

This year's Palestine Cinema Days didn't just focus on Palestine's budding film industry, but also gave a platform to women's empowerment.

Under the banner of No Means No, the week-long event beginning on October 2 addressed gender-based violence and women's representation in film.

No Means No is an initiative at film festivals worldwide aiming to raise awareness about violence against women. The campaign first launched at the Carthage Film Festival in Tunisia last year. But Khulood Badawi, Palestine Cinema Days spokesperson, said the festival's organisers wanted to spread this message across the Arab World.

"Violence against women is a global problem and we Palestinians see ourselves as part of that global movement and part of the international film industry," Badawi said.

|

Violence against women is a global problem and we Palestinians see ourselves as part of that global movement and part of the international film industry |  |

"Everyone thought we chose this topic because of Israa," Badawi added. "But unfortunately, it's not because of her. Violence against women is not exceptional in our community."

The No Means No programme at Palestine Cinema Days consisted of four documentaries made by female directors and a panel featuring international lawmakers, activists and filmmakers discussing women's rights and women's role in cinema.

During the panel, Debra Zimmerman, Executive Director of not-for-profit Women Make Movies, admitted that throughout her decades of filmmaking, women's representation remains stagnant.

"Only one-third of the speaking parts of the top 100 films were women," Zimmerman said. "Our voices are only being heard one-third of the time."

|

|

| Read also: 'No honour in murder': Honour killings are a problem and we know it |

In Arab cinema, Badawi explained women are seen as dependent on men.

"She has no role, she has no leadership, she has no voice, she's always someone who belongs to her man," Badawi said. "You don't see a woman who makes decisions or has an independent life or character."

While Zimmerman maintains women's representation is lacking on screen and behind the camera, she remains optimistic.

"In almost every place there's a panel like this, there's conversations happening," Zimmerman said, referencing the No Means No forum she was a part of.

"No Means No is really having an impact, particularly on younger women who I think are seeing more women role models as creators of their own image."

Adding a social element to the film festival derived from the notion that cinema can have a powerful impact on society.

"Cinema is an important tool to change mentality and highlight issues," Badawi said. "It's a tool that we should use in order to make a change in the community."

|

She has no role, she has no leadership, she has no voice, she's always someone who belongs to her man... You don't see a woman who makes decisions or has an independent life or character |  |

Palestine Cinema Days attendees agreed art and culture can alter the public's perspective and spur change.

"Cinema can shed light on the issue," Lama Hourani, Palestine Programme Manager at International Media Support, an NGO promoting press freedom and a Palestine Cinema Days sponsor, said.

"Films raise awareness and can sometimes help change the laws."

Hourani noted how Violently in Love, one of the documentaries part of the No Means No programme, helped reform laws in Denmark to include psychological violence as a form of domestic violence.

"Women's rights activists can use film to advocate and lobby for changing legislation or customs," Hourani said.

Watan Sabbah, a No Means No panellist, acknowledged films can influence society, but she said the discussion on women's rights can't take place in a bubble. Feminists need to go outside their circle to encourage change.

"The people that came to the conference are women's rights organisations," Sabbah said, expressing that the panel's participants are already aware of Palestine's gender discrimination issues. "We must speak to people with less education and poor people."

While the root cause of gender violence in Palestine is due to the absence of a legislative framework to protect women and ensure accountability, reforming the legal system isn't enough. Human rights organisers stress patriarchal traditions and toxic masculinity has continuously penetrated into Palestinian daily life.

"We need to also get rid of the shame-based society," Zoughbi Alzoughbi, Founder and Director of Wi'am: The Palestinian Conflict Transformation Center, said. "Otherwise we will be prisoners of the past."

But Ghrayeb's murder in August seemed to set off alarm bells in the region. September saw a wave of protests throughout Palestine and Israel calling for justice and an end to femicide.

Sabbah believes Ghrayeb's death helped liberate the conversation on women's inequality. Palestinian women can now talk more openly about gender-based violence because they identified with Ghrayeb and felt connected to her experience.

"The culture in Palestine understands Israa more than any story before," Sabbah said.

And while Palestinian women's rights campaigners are working tirelessly to pass the Family Protection Bill, which would empower victims and prevent violence against women, Badawi thinks the duty can't just rest on civil society organisations.

"It is not only the responsibility of feminist organisations," Badawi said. "It's a shared responsibility where the media can produce the image and knowledge."

To Badawi, cinema can change how we think and the public's perception of women – just by seeing stronger female characters on screen.

"It's important to take the woman's status from the vulnerable one to the more empowered one."

![Palestinians mourned the victims of an Israeli strike on Deir al-Balah [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2024-11/GettyImages-2182362043.jpg?h=199d8c1f&itok=xSHZFbmc)

![The law could be enforced against teachers without prior notice [Getty]](/sites/default/files/styles/image_684x385/public/2178740715.jpeg?h=a5f2f23a&itok=hnqrCS4x)