Japanese-Americans unite with Muslims against Trump's immigration plans

The Japanese-American internment - subsequently ruled unconstitutional by the US Supreme Court - is an example of the perils of rule by presidential proclamation and discriminatory policymaking, they say. And they call their activism a rubric for cross-community, cross-faith, cross-gender organising in the time of Trump.

An impromptu vigil for intra-communal support in Los Angeles' Little Tokyo on Thursday night - called amid news that Trump would finally sign an order to ban people from select Muslim-majority nations from entering the United States - drew hundreds from far beyond the Japanese and Muslim American communities.

It's one of several such gatherings in the months since Trump's election.

"I will put myself on a registry before Muslims," said 36-year-old Kyoko Nakamaru, who identifies as a biracial Japanese-American activist.

Nakamaru's family was interned at camps across the United States for four years beginning in 1942, after then President Franklin Delano Roosevelt proclaimed that "enemy aliens" of Japanese, German and Italian descent had to register.

About 120,000 Japanese Americans were rounded up for incarceration.

The late US Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia warned, in a 2014 talk at the University of Hawaii, that the internment might happen again.

"The internment dramatically affected every part of my family's life. The very notion we would consider repeating this travesty is horrifying. I will do everything in my power to make sure there is no Muslim ban and registry," Nakamaru said.

|

The internment dramatically affected every part of my family's life. The very notion we would consider repeating this travesty is horrifying. I will do everything in my power to make sure there is no muslim ban and registry |  |

|

|

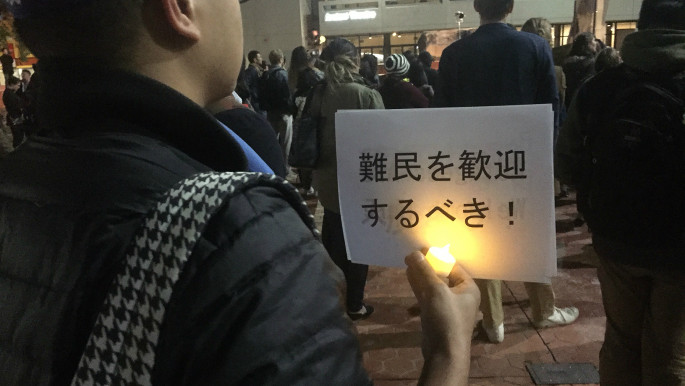

| Protester Chris Lapinig holds a sign in Japanese reading: "We welcome refugees" [Massoud Hayoun] |

The Internment - the Japanese-American community's shorthand for their elders' wartime incarceration - is a poignant emblem of what to fight against in America's future, not just for Japanese-Americans, but for all Angelenos, the protesters say.

"As a Muslim American, but also an American [the legacy] is poignant. I have friends whose families were in the camps - parents or grandparents," said Azim Khan, a 34-year-old librarian who participated in the rally. Khan is a Muslim whose parents are of Punjabi and mixed European origin.

|

|

Blocks away, on 1st Street, beside the Japanese American National Museum is the site where Japanese Americans were told to line up for relocation to the camps. Three-quarters of a century ago, signs were posted up and down the street calling for people of Japanese origin to register.

In December 2015, after first announcing that he would ban Muslims from entering the US as a presidential campaign platform, Trump cited Roosevelt's Second World War proclamations. "Take a look at presidential proclamations, what he was doing with Germans, Italians and Japanese, because he had to do it," Trump was quoted as saying by the New York Post.

Reuters news agency on Wednesday reported that Trump would issue an executive order banning visas for people from seven countries, including Syrian refugees, for at least 30 days. Drafts of the order reported by CNN and others revealed the countries were all Muslim-majority, and six of seven were in the Arab League: Iraq, Syria, Iran, Sudan, Libya, Somalia and Yemen.

The ban is seen as a possible precursor to what Trump's pre-inaugural team suggested would be a proposed registry of "immigrants from Muslim countries".

"The one silver lining is it is mobilising people. People who wouldn't normally come out are," said Kristin Fukushima, 29, managing director for the Little Tokyo Community Council. Her family was imprisoned in the Second World War-era camps.

"I hope this is the start of a sustained movement where we are uplifting each other and knowing we can only do this if we can all come together."

|

The one silver lining is it is mobilising people. People who wouldn't normally come out are. I hope this is the start of a sustained movement where we are uplifting each other and knowing we can only do this if we can all come together |  |

The relationship growing between the Japanese American and Muslim American communities is one that hopes history will help influence the present.

“Because of our history, it’s a responsibility. A duty,” said Traci Ishigo, the 25-year-old Japanese-American co-chair of #VigilantLove, one of the advocacy groups behind Thursday's event.

"We're harnessing our support among communities - making connections between the Japanese-American camp experience and what's been happening today."

Ishigo's #VigilantLove co-chair, Sahar Pirzada, 27, whose parents emigrated from Pakistan, agreed.

"A big part of it is that their experience of being in the camps and being discriminated against and questioned as to their loyalty has left a scar in the community and drives them to show up for [the Muslim American community]. For the Muslim American community to not respond to that sign of solidarity and build would be un-Islamic."

At the event on Thursday, speakers repeatedly entreated participants to "meet someone new" - to build networks.

That's a big part of Pirzada and Ishigo's game plan for a rapidly changing future.

"I think moving forward, we want to build a base of folks that want to spread vigilant love and activate that base when there's a need - God willing there won't be a need," Pirzada said.

The solidarity goes both ways. Japanese Americans on February 19 will commemorate the 75th anniversary of the incarceration of their community during the Second World War by presidential order. The young women will work together with their coalition to prepare for commemorations of the Day of Remembrance.

The strength of their movement is intersectionality, the participants in Thursday's vigial said.

"There is no future without intersectionality. It's the responsibility of those who have privilege to centre those who do not," said Nakamaru.

Ishigo agreed, "We need to resist the patriarchy in all its forms."

|

We need to resist the patriarchy in all its forms |  |

|

|

| Steven Wong and the children hold signs showing Asian American social justice activists Grace Lee Boggs and Yuri Kochiyama [Massoud Hayoun] |

Ishigo explained that #VigilantLove started with a partnership between Japanese Americans and Muslim Americans that began with post-9/11 solidarity to combat systemic racism and what was seen as state-sanctioned Islamophobia. But it's already growing beyond these two communities.

Avital Aboody, a 30-year-old member of Jewish Voice for Peace, an advocacy group that organises for Palestinian rights and social justice, is of Iraqi Jewish origin. For her, her Iraqi origins are "part of my identity and something that does motivate me to support that community more. But I think that I would be here anyway as a person of conscience who supports human rights".

|

There's a lot more work on that happens for us than we're given credit for, I think because of the fear of us coming together... Because we're breaking down white supremacy – white patriarchy |  |

Isela Gracian, 36, is a Mexican American and president of the East LA Community Corporation. For her, events like Thursday's - one in a movement for inter-communal solidarity - are a challenge, an "y que? And what?" to the new administration. Cross-community organising is nothing new in LA, but many may not have noticed these ties being forged over decades, Gracian said.

"There's a lot more work on that happens for us than we're given credit for, I think because of the fear of us coming together," Gracian said. "Because we're breaking down white supremacy - white patriarchy."

An executive order on Wednesday called for the creation of a wall at the US' southern border with Mexico. The father of Gracian's seven-year-old child is an undocumented American, one of the communities targeted by Trump's proposals.

But Gracian is confident she will find support from people like Pirzada and Ishigo.

"We are learning from the past moments," she said. "What we're leaning on today is the love, the cultural connection. And that is our fight against Trump and his administration's racist policies."

Massoud Hayoum is a freelance journalist and analyst who has reported for Al Jazeera America, The Atlantic, AFP and the South China Morning Post.

Follow him on Twitter: @mhayoun

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News