What Kurdish federalism means for Syria

Thursday morning saw two separate but related incidents.

First, in Turkey, the Kurdistan Freedom Hawks (TAK) claimed responsibility for the March 13 suicide bombing in Ankara that massacred 37 people.

The second was a declaration in Syria by the Democratic Union Party (PYD) and its armed wing, the People's Protection Units (YPG), that they were forming a federal zone in the north of the country.

The link is simple: the Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK).

The PYD is the Syrian wing of the PKK. This is not only true in command terms, but the PYD is organically part of the PKK's transnational network to the point where nearly half of the PYD's casualties are Kurds holding Turkish citizenship.

And while TAK has purportedly split from the PKK, there is reason to doubt this. TAK's suspected leader, Bahoz Erdal - born Fehman Hussein - is a Kurd from Syria who has been among the top three PKK commanders since 2004. Kurdish analysts have said Erdal leads a faction of the PYD.

The PYD is currently the US' favourite proxy inside Syria in the fight against the Islamic State group. The US fell into alliance with the PYD by accident after the Kobane episode, and has backed the PYD to the hilt ever since.

Washington even backed the PYD after the group exploited Russian airstrikes in mid-February 2016 to conquer areas of northern Aleppo, in a bid to complete its demographic project by connecting cantons in north-eastern and north-western Syria - attacking US- and Turkish-backed opposition groups in the process, and provoking the Turkish military into shelling PYD positions in an (unsuccessful) effort to halt them.

It is in this context that the claim by the Turkish government that the Ankara suicide bomber received training from the PYD should be taken. While it is not impossible, this is a message aimed squarely at the United States.

The US position is that the PYD is "not affiliated" to the PKK, which is a US-listed "terrorist organisation".

Fully accounting for the heavy-handed response of the Turkish government - which continues to this day - the PKK's authoritarian nature, methods of warfare, and the at least 40,000 people who have been killed in its off-and-on insurgency since 1984 would make any state regard it as a threat.

And while the PYD has maintained a formal denial about its reported PKK links, its fighters are less circumspect. Among other things, PYD fighters have been seen on video saying that the PKK's fight in Turkey is their own, and one PYD foreign fighter called for recruits to carry out attacks against Turkey.

Though it is a decidedly unpalatable view in the West, Turkey views a Kurdish state on its border, especially one run by the PKK, as a more dire threat to its national security than the Islamic State group's would-be "caliphate".

|

One can see why the PKK is seen as the more serious long-term menace in Ankara |  |

At this moment, the internal terrorist threat from the PKK and IS is, according to Ankara, probably about equal in Turkey. But in the context of an international opinion that would probably agree to a PKK statelet in Syria - even if such were regarded by the Turks as little more than a terrorist base - while never countenancing that IS could remain in place, one can see why the PKK is seen as the more serious long-term menace in Ankara.

The federalism declaration by the PYD is thus regarded in Ankara with something akin to the horror that the rest of the world felt at IS' declaration of its caliphate. And the disquiet about the PYD's increasing assertiveness is by no means limited to Turkey.

The PKK has very deep and old connections with Russia and the Assad regime. The PYD's direct ties to the Assad regime have been noted by the British government, and of course that means the PYD collaborates with Iran's Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, which controls Assad's security sector.

|

|

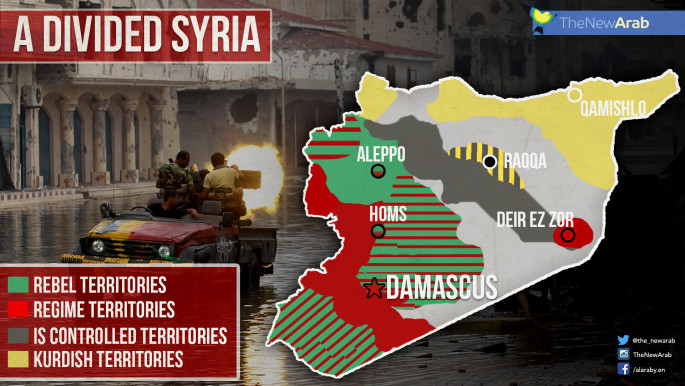

| [click to enlarge] |

Widespread opposition

But even pro-regime forces oppose the Kurds' latest move: the Syrian identity, which rejects partition, is one of the few things left uniting loyalists and oppositionists.

For the opponents of the Assad regime and its Russian and Iranian supporters, the disapproval of this move by the PYD is near-unanimous - and not only for ideological reasons.

"Russia has multiple objectives in Syria and first among them is preserving the regime," Tony Badran, a research fellow at the Foundation for the Defence of Democracies, told me.

From the earliest days of its intervention last September, Russia targeted the mainstream rebellion in Syria, not IS, which actually expanded under Russian airstrikes.

"In order to secure the regime long-term, you need to also shut down the Turkish border," Badran continues. "The Russians have been clear that the PKK/YPG Kurds are the suitable instrument [for achieving this]."

If the PYD's "state" along Turkey's border becomes a reality then Syria will have, as Badran has elsewhere explained, "a US-recognised Iranian [and Russian] zone [in the west], which cooperates with a US- and Iranian-backed Kurdish zone [in the north, and in in the case of Syria, unlike Iraq, this zone is entirely hostile to Turkey], and then a third, Sunni Arab, kill-zone in between".

|

There is a strong case that in a settlement to the Syrian crisis there should be a decentralisation of power |  |

In this scenario, the rebel pocket in the south on the Jordanian border would be isolated from the rebel pocket in the north; the rebellion would be hemmed in - and either forced into a political settlement, in a regime victory in all-but-name or eliminated entirely. At this point the regime's intention would be to make this conflict a binary choice between the dictator and the terrorists, and the outside world will pick the dictator, despite his intensive role in building up the terrorists.

There is a strong case that in a settlement to the Syrian crisis there should be a decentralisation of power, but the indications the PYD have given of what they intend to rule is not encouraging; the PYD trying to conquer and rule Arab areas such as Jarabulus and Azaz will set the stage for a conflict that will outlast both the revolution and IS.

Unfortunately, this has been enabled at every stage by the US, which refused to back its own allies when the Russians intervened and tilted toward Iran/Assad and the PYD, creating an imbalance so stark in the case of the latter that the PYD was emboldened to attack other US assets in Syria with Russian help.

"The experience of countries like the US shows that federalism can be a successful system," as Hussain Abdul-Hussain, the Washington bureau chief of al-Rai put it to me.

"The problem with Assad and Putin is that their kind of federalism is designed to serve an autocrat at the centre who remains in power indefinitely while handing over provincial affairs to opponents to fight over."

In Syria, the formation of a PYD maximalist statelet at this point would weaken the mainstream rebellion that is needed to dismantle IS in its heartland, cutting off its support and heightening sectarian tensions that work to the advantage of the extremists - both within the insurgency and the regime.

The international coalition would also be split. It would consign most of Syria to indefinite chaos, as the state-building and demographic projects of the regime and the PYD focused on their own internal affairs while deriving legitimacy and international support amid the ongoing mayhem.

And, worst of all, for the price of re-legitimising a criminal regime, the world would have created an environment in which IS thrives.

Kyle Orton is a Middle East analyst and an associate fellow at the Henry Jackson Society. Follow him on Twitter: @KyleWOrton

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News