Remembering the radical thought of Nasr Hamid abu Zayd

Remembering the radical thought of Nasr Hamid abu Zayd

Blog: The Egyptian theologian died five years ago, after being persecuted for his ideas, leaving a legacy of radical Arab-Islamic thought.

4 min read

Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd's theology continues to influence Islamic thinkers [YouTube]

The Islamic theologian and philosopher Nasr Hamid Abu Zayd died five years ago in Cairo from an unknown virus, amid battles with the Mubarak regime, as well as extremists, over his ideas.

Abu Zayd was first imprisoned aged 12 for allegedly sympathising with the Muslim Brotherhood. He had learned the Quran by heart by age eight.

He completed his education at Cairo University, and became an associate professor in Islamic studies, where much of his work concerned the interpretation of the Quran.

Nasr Hamed abu-Zayd advocated a more "humanistic" idea about interpreting the Quran, Islam’s holy book which Muslims believe was passed to Mohammed from God.

Unpopular opinions

Abu-Zayd famously believed that, although the Quran's "divine sources" should not be questioned, one should take into consideration "the historical and cultural context" of the language - and therefore its content - which would allow for the easier adaptation of Islamic ideas to contemporary times and contexts.

He was denied a full professorship at Cairo University as a result, and his problems began in earnest.

After a trial in 1995 in which he was sued by an Egyptian citizen, he was declared to be an "apostate", and was consequently divorced from his wife, Dr Ibtihal Younis, a French professor at Cairo university - as Muslim women are not permitted to be married to non-Muslim men.

"When we lived in sin no one paid attention," joked Dr Younis to the Independant at the time. "Now we are respectably married, they [fundamentalists] want us divorced."

Like the assassination of liberal Professor Farag Fouda, abu-Zayd's case witnessed the alignment of the Mubarak regime and Islamist elements; with the former trying to placate the latter.

The trial was also the first in Egypt to declare apostasy - which was not formally recognized by Egyptian law, and was carried out under the basis of hisba, that allowed an individual to charge someone in the name of society, if "the values of Islam" are thought to be threatened.

Nasr Abu Zayd was forced into de-facto exile and he took a post teaching Islamic philosophy in the Netherlands.

'Free thinker'

Shortly after the trial, the academic committee at Cairo University accepted his promotion

"He is a free thinker, aspiring only to the truth. If there is something urgent about his style, it stems from the urgency of the crisis which the contemporary Arab-Islamic World is witnessing," academics wrote.

Abu-Zayd's critique of contemporary Islamic thought was built neither upon European enlightenment ideals nor secularism, but was embedded in Islamic thought and history, utilising the work of Islamic schools and thinkers from the Islamic golden age, such as 12th century philosopher Ibn Arabi.

"I'm sure that I'm a Muslim. My worst fear is that people in Europe may consider and treat me as a critic of Islam," he said.

"I'm not a new Salman Rushdie, and don't want to be welcomed and treated as such."

This approach contrasted with some contemporary secular Muslims' critique of Islam. Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Irshad Manji, for example, are frequently accused of relying upon Western ideals to counter mainstream Islamic thought, sometimes using this as a justification to defend Western foreign policy in the region.

Limits of language

Yet, despite the troubles Nasr Hamed abu-Zayd faced in Egypt, and with his co-religionists in the region, he never sought asylum abroad, continued to work within Arab and Islamic schools of thought, as well as defending regional causes, while stressing that problems in the region could not be blamed on religion.

The controversy in his work lay in his ideas surrounding "God and communication".

Whereas mainstream Islamic thought and belief rests on the idea that the Quran is the literal word of God, Zayd argued, citing the Quran and other Islamic texts, that the oneness and all-encompassing nature of God was unable to fully confine itself to human language and words.

"I treat the Quran as a nass [text] given by God to the Prophet Muhammad. That text is put into a human language, which is the Arabic language," he said.

"When I said so, I was accused of saying that the Prophet Muhammad wrote the Quran. This is not a crisis of thought, but a crisis of conscience," he said.

Opening new debates

His ideas remain controversial within mainstream Islam, and many Muslims and Muslim theologians disagree with him - as they feel his ideas travel too far from the basic tenets of Islam.

However, he arguably opened new theological debates within Islam, and gave an alternative Islamic theoretical framework to Muslims struggling with aspects of mainstream belief.

Many in the region, especially young people, are influenced by his views and find themselves in the same predicament - trapped between dictatorships and extremists, as the two groups use each other for their own ends.

Egyptian novelist Youssef Rakha wrote that abu-Zayd's prose allows him "to relax in bed knowing not only where I stand but also that it makes sense to stand there as a Muslim, however agnostic, however disappointed in contemporary Islam".

This peice has been edited to include source links

Abu Zayd was first imprisoned aged 12 for allegedly sympathising with the Muslim Brotherhood. He had learned the Quran by heart by age eight.

He completed his education at Cairo University, and became an associate professor in Islamic studies, where much of his work concerned the interpretation of the Quran.

Nasr Hamed abu-Zayd advocated a more "humanistic" idea about interpreting the Quran, Islam’s holy book which Muslims believe was passed to Mohammed from God.

| When we lived in sin no one paid attention. Now we are respectably married, they [fundamentalists] want us divorced. - Ibtihal Younis, wife |

Unpopular opinions

Abu-Zayd famously believed that, although the Quran's "divine sources" should not be questioned, one should take into consideration "the historical and cultural context" of the language - and therefore its content - which would allow for the easier adaptation of Islamic ideas to contemporary times and contexts.

He was denied a full professorship at Cairo University as a result, and his problems began in earnest.

After a trial in 1995 in which he was sued by an Egyptian citizen, he was declared to be an "apostate", and was consequently divorced from his wife, Dr Ibtihal Younis, a French professor at Cairo university - as Muslim women are not permitted to be married to non-Muslim men.

"When we lived in sin no one paid attention," joked Dr Younis to the Independant at the time. "Now we are respectably married, they [fundamentalists] want us divorced."

|

|

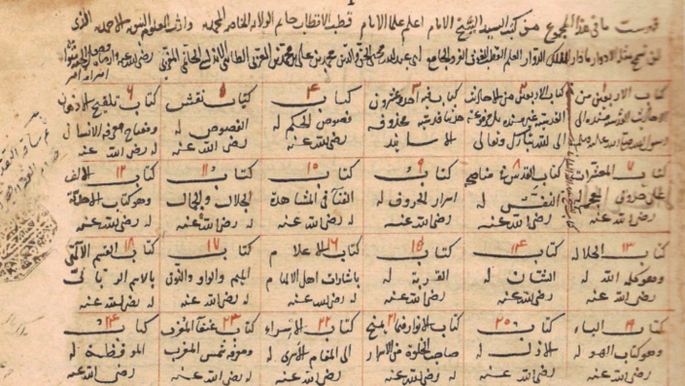

| A partial list of works of Ibn Arabi, a 12 century philosopher who influenced abu-Zayd [AFP] |

The trial was also the first in Egypt to declare apostasy - which was not formally recognized by Egyptian law, and was carried out under the basis of hisba, that allowed an individual to charge someone in the name of society, if "the values of Islam" are thought to be threatened.

Nasr Abu Zayd was forced into de-facto exile and he took a post teaching Islamic philosophy in the Netherlands.

'Free thinker'

Shortly after the trial, the academic committee at Cairo University accepted his promotion

"He is a free thinker, aspiring only to the truth. If there is something urgent about his style, it stems from the urgency of the crisis which the contemporary Arab-Islamic World is witnessing," academics wrote.

Abu-Zayd's critique of contemporary Islamic thought was built neither upon European enlightenment ideals nor secularism, but was embedded in Islamic thought and history, utilising the work of Islamic schools and thinkers from the Islamic golden age, such as 12th century philosopher Ibn Arabi.

"I'm sure that I'm a Muslim. My worst fear is that people in Europe may consider and treat me as a critic of Islam," he said.

"I'm not a new Salman Rushdie, and don't want to be welcomed and treated as such."

This approach contrasted with some contemporary secular Muslims' critique of Islam. Ayaan Hirsi Ali and Irshad Manji, for example, are frequently accused of relying upon Western ideals to counter mainstream Islamic thought, sometimes using this as a justification to defend Western foreign policy in the region.

Limits of language

Yet, despite the troubles Nasr Hamed abu-Zayd faced in Egypt, and with his co-religionists in the region, he never sought asylum abroad, continued to work within Arab and Islamic schools of thought, as well as defending regional causes, while stressing that problems in the region could not be blamed on religion.

| I'm not a new Salman Rushdie, and don't want to be welcomed and treated as such - Abu-Zayd |

The controversy in his work lay in his ideas surrounding "God and communication".

Whereas mainstream Islamic thought and belief rests on the idea that the Quran is the literal word of God, Zayd argued, citing the Quran and other Islamic texts, that the oneness and all-encompassing nature of God was unable to fully confine itself to human language and words.

"I treat the Quran as a nass [text] given by God to the Prophet Muhammad. That text is put into a human language, which is the Arabic language," he said.

"When I said so, I was accused of saying that the Prophet Muhammad wrote the Quran. This is not a crisis of thought, but a crisis of conscience," he said.

Opening new debates

His ideas remain controversial within mainstream Islam, and many Muslims and Muslim theologians disagree with him - as they feel his ideas travel too far from the basic tenets of Islam.

However, he arguably opened new theological debates within Islam, and gave an alternative Islamic theoretical framework to Muslims struggling with aspects of mainstream belief.

Many in the region, especially young people, are influenced by his views and find themselves in the same predicament - trapped between dictatorships and extremists, as the two groups use each other for their own ends.

Egyptian novelist Youssef Rakha wrote that abu-Zayd's prose allows him "to relax in bed knowing not only where I stand but also that it makes sense to stand there as a Muslim, however agnostic, however disappointed in contemporary Islam".

This peice has been edited to include source links

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News