Refugees and democracy are dying at Europe's front door

The European Union (EU) and European countries grappled with how to respond to the 2015 refugee flow, and the issue became an Achilles heel causing political chaos. The EU attempted to manage the situation through providing monetary incentives to Turkey for closer patrol of the borders, effectively ending the European "crisis" and ignoring the humanitarian disaster occurring in Syria.

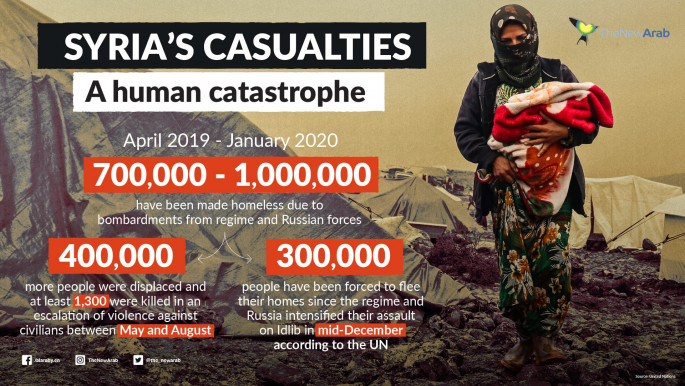

The world refused to act on Syria's growing humanitarian catastrophe, and In 2018 the country ranked first on the UN poverty index. In 2019, according to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 83 percent of Syrians lived in poverty while 70 percent lived in extreme poverty.

But the international community collectively hoped the problem would resolve itself, or that someone else would fix it for them, hoping that someone would be Turkish President Recep Erdogan.

Turkey's recent decision to open the border with Europe sparked a torrent of condemnations.

Ankara was criticised for creating a dangerous situation for refugees, Athens for their brutal treatment of asylum seekers, and the EU for their continued inability to enforce asylum law.

As a world community, we are treating Syrians almost as badly as Bashar al-Assad himself.

|

The international community collectively hoped the problem would resolve itself |  |

Insulted for leaving and accused of being terrorists if they stay, Syrians were now facing few options other than death, so Turkey opened its borders. While far fewer have attempted to cross in the last 48 hours, Turkey has refused their latest monetary enticement to close the borders.

Erdogan will remain in a tug-of-war with Europe over borders. And despite the risk of death, refugees from around the world will inevitably continue to seek refuge in Europe.

Erdogan's "Open Door" policy served as a provocation - a means to elicit a European response by lobbing refugees at the EU's front door like cannon fodder, but it will do little to force open the EU's gates.

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

The concept of "Fortress Europe" is not new. Its roots can be traced to Spain's Reconquista and it also appears in some World War II propaganda. Islamophobia and anti-Semitism are historic prejudices engraved into Europe's past - a wicked problem that EU acknowledges.

Today, notions of racial and religious superiority prevail, and lend credence to the notion of Europe's right to maintain border security at any cost. As European countries vigorously assert their right to "security", asylum seekers are continually denied the right to apply for asylum in Europe.

So called "economic migrants" are altogether excluded from consideration under asylum law. The EU continues to draft laws to prevent both asylum seekers and economic migrants from entering Europe. Since 2015, these policy initiatives have failed to address the causes of large refugee flows, and Europe again is faced with a mounting crisis.

The situation on the Turkish-Greek border today is different from 2015, when there was a worldwide outpouring of sympathy for asylum seekers. Today, that expression of goodwill does not exist. This time, the "Refugees Welcome" movement was met with an equally forceful populist sentiment that often turns to violence in rejecting refugees.

|

A continued policy of inaction and American-style isolationism will not stop the Turkish volley of refugees |  |

Right leaning and openly racists politicians have been elected throughout Europe, including in countries that host few refugees, as is the case in Hungary and Poland.

A backlash against Muslim refugees, cast as "invaders" is fueling these hardline reactions. Erdogan is banking on Europe's historic animosity towards Muslims, and growing Islamophobic movements. He knows the only thing Europe desires less than military involvement in Syria against Assad, is an increase in Muslim refugees.

The victims of western and Russian aggression, economic migrants, and Syrians make up the convoys of the latest refugee arrivals. The hemorrhaging caused by the Syrian war has only added to a world already bleeding and anemic. It has exposed the gross inequities in the application of international law, and a thread bare democratic system.

In the wake of the massive destruction caused by two world wars, mankind, under the auspices of a newly minted United Nations, agreed to draft a charter to ensure basic rights to all of humanity. It was the expansion of democratic ideals on a global scale.

Read more: Syria's brutal war enters 10th year

But traditionally, democracy has not been inclusive; a domain confined to white, privileged, landholding males. The rehabilitation of democracy to be truly inclusive is a recent endeavour, an experiment that is struggling to continue, and is under siege by populous movements and far-right extremists.

Inclusion, representation and the rule of law became the hallmarks of this new democratic system. Yet, with few exceptions, asylum seekers and economic migrants continue to be excluded.

The EU's fallback policy response remains one of reluctance, or impotence to mount a coherent response to refugees. The EU's pledge of 700 million euros to aid Greek border militarisation is a temporary solution.

The EU cannot block refugees forever, nor must Greece be allowed to shoot or drown asylum seekers. Erdogan will threaten to hold the door open until the EU and NATO support Turkey's military operation in Northern Syria, or enforce a no-fly zone.

A continued policy of inaction and American-style isolationism will not stop the Turkish volley of refugees, nor will escalating the violence against refugees and humanitarian workers.

European countries and the EU need to work collectively to provide long-term solutions uncoupled to security issues, and begin to address the underlying causes of refugee flows. Together, they can do it. How Europe responds to the escalation of violence in Syria and on the Turkish-Greek border will determine the future of law and democracy in Europe.

Anisa Abeytia is a research and policy professional focused on Syria, integration, social inclusion and the refugee crisis in Europe with a background in international development, humanitarian diplomacy and postcolonial thought. She holds an MA from Stanford.

Follow her on Twitter: @AbeytiaAnisa

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News