Decolonising INGOS: MSF has a fundamental flaw its white saviours can't solve

The medical humanitarian organisation is a massive operation, composed of five operational centres in Europe, each with their respective branch offices around the world, a budget of over 1.8 billion dollars, and operations in more than 70 countries worldwide, tackling medical emergencies related to conflict, pandemics, natural disasters, exclusions to healthcare, and other spaces where few other iNGOs dare to venture.

The fuel that allows this miraculous machine to function is the 70,000 workers, medical and non-medical, of which over 90 percent are "national staff" (i.e. people hired by MSF to work within projects or offices within that country). Thes rest are "expats", often dispatched for senior positions on a temporary basis overseeing and running the projects.

From 2015 to 2019, I worked for MSF in the communications department of its emerging branch office in Beirut. I visited MSF projects in Greece, Lebanon, Egypt, Iraq, and Yemen where I had the privilege of meeting and hearing the stories of incredible human beings – the staff and patients – struggling, surviving, and trying their best in the most brutal circumstances.

There are many reasons to applaud MSF, like its decade-old reconstructive surgery hospital for victims of war wounds, the search-and-rescue boats launched in the Mediterranean Sea, or its campaign to pressure pharmaceutical companies on life-saving medication to name a few, and credit where credit's due.

|

A snapshot of leadership positions at MSF reveals that it is almost exclusively the domain of white, European men |  |

Despite these astonishing feats of humanity, the long and complicated story of the international humanitarian sector's involvement in the Middle East and North Africa continues today. It's a history rooted in European colonialism, shaped by post-WWII considerations and Cold War tussles, and dictated today by a hegemonic western understanding of "humanitarian values" and its scope of action.

MSF - as progressive as it is within its sector - is not insulated from these biases, ideologies, positions, politics, and history or the prevalence of sexual harassment, labour exploitation, institutional racism and manifestations of unacceptable behaviour.

MSF is highly colonial in structure, and perhaps has one of the worst records on labour rights. In addition, discrimination based on race, gender, sexual preference, and culture are all prevalent. Those inherent structural biases are intrinsically linked how the medical organisation has grown since its founding in 1971 by a group of French doctors and journalists.

|

|

A snapshot of leadership positions at MSF reveals that it is almost exclusively the domain of white, European men. Meanwhile, the "national" workforce (90 percent percent of MSF's total workforce) is restricted from these positions of power (justified on security and neutrality grounds) and has few opportunities to grow within MSF's system.

This all occurs despite the fact that greater risks are borne by the "national staff" and they are often the first victims of MSF's dangerous work. One of the worst - and often neglected - moments in MSF's history is the murder of hundreds of Rwandan national staff during the genocide in 1994.

Other symptoms of institutional racism manifest themselves across all levels of the organisation; from funding, recruitment, salary distribution, promotion opportunities, to communication strategies, advocacy considerations, office culture and quality of care.

The impact of these factors on quality of care for patients showcases how ultimately self-defeating and restrictive the ongoing existence of institutional racism is on humanitarian organisations like MSF. The Middle East and North African context vexes MSF immensely even though it has been in and out of the region since 1976. It was after 2011, with the eruption of the Arab uprisings, in which MSF found itself increasing its projects and offices to respond to the growing needs.

|

My own attempts to talk about institutional racism in MSF, and those of my PoC colleagues were met with surprise and dismissals |  |

Unlike other more resource limited contexts, MSF often found itself facing existential crises due to the fact that the patients and national staff were demanding a quality of care that is higher and more vigorous than MSF's usual modus operandi. And in terms of access and advocacy, attacks on hospitals and medical personnel have taken a significant toll on the organisation.

In Palestine, these dynamics really come to the fore, where MSF's positioning is heavily shaped by North American and European understandings of the conflict. Their work there is arguably admirable - it runs mental health programmes in the West Bank and has burn and trauma centers in Gaza, for example. But it was muted about the intentional targetting and killing of Palestinian medical workers, and appeared unwilling or incapable of directly identifying the Israeli occupation as a negative effect on the health of the Palestinians, until only a few years ago.

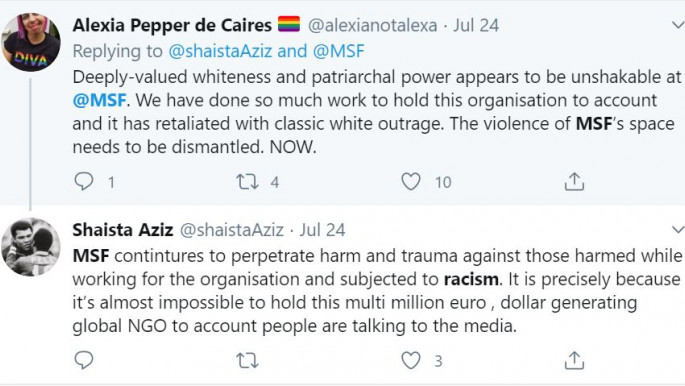

Twitter Post

|

MSF is very hesitant to take a strong stance on Palestine and the right of return, because on a foundational level, it sees them through a European and North American lens; purely political, and always flattened to two equal sides of the conflict, rather than what is really is: A struggle against a settler-colonial state and a violation of the essential principles of humanitarianism, international law and refugee rights.

Read more: MSF closes Kabul program after May maternity hospital attack

Moreover, the common mantra that justifies MSF's tame position on Palestine often centres on the concern that they will be kicked out by Israel, or lose a large chunk of funding that comes in from North America; almost a quarter of MSF's total budget. The question of loss of funding, requires a moment's pause, for it illustrates how MSF's 'financial independence' is actually shaped by private donor considerations, rather than what the needs are.

The result is not only a very superficial form of humanitarian action that fails to tackle the causes and is confined to alleviating the symptoms, but more dangerously it weakens MSF's ability to challenge other states and their brutality, such as the Assad regime in Syria and the Saudi regime in Yemen. For MSF to be successful in the 21st century, it will have to embrace its own propaganda about being an international movement and address this inadequacy.

The issues within MSF have been spoken about by People of Colour (PoC) staffers for a long time. There have been numerous workshops, training sessions, committees and reports. However, these "diversity and inclusion" efforts have been largely unsuccessful. They have failed to adequately engage issues of equity, justice and representation. They have not recognised the white supremacy and racism built into the organisation, and have homogenised a diversity of racial, ethnic and cultural groups, failing to address the systemic racism that persists.

In general, my own attempts to talk about institutional racism in MSF, and those of my PoC colleagues were met with surprise, dismissals, "whataboutisms", charges of reverse racism, "all lives matter" rhetoric, or vague promises for change with no real action plan or timeline.

Most recently, and inspired by Black Lives Matter, MSF workers have organised themselves to challenge the leadership and demanded radical change. An open letter signed by over 1,000 staff noted MSF's historical failings, and its lackluster approach in tackling these racist structures in recent years. They assert their belief that "[e]xclusion, marginalisation and violence are inextricably linked to racism, colonialism and white supremacy, which we reinforce in our work".

|

Ultimately, the courage that is required from those in power that is necessary for change, has so far been absent |  |

The open letter ends with 10 crucial demands, including a radical re-imagination of MSF's approach to humanitarian action that centres affected individuals and communities and seeks to redress decades of power and paternalism; and an independent, external review to explore the history of colonialism, expressions of neo-colonialism, and manifestations of white supremacy in all aspects of MSF's work.

This is a watershed moment for MSF. If it can shift away from its own troubling roots and actively become an actively anti-racist organisation that is truly international and humanitarian, composed of a unified global workforce where all have opportunities and access, it would have major ramifications for the humanitarian sector.

Ultimately, the courage that is required from those in power that is necessary for change, has so far been absent, save their recent pledges to do better. And those who enjoy power, no matter how well-intentioned, have significant difficulty in surrendering it. After all, power is intoxicating and addictive, particularly when one it is perceived to be in service of the 'Greater Good'. But radical change isn't going to happen without power being forgone.

This leaves us with another option. Considering that the needs in our region are acute and only going to get worse, we need a medical humanitarian organisation that can provide assistance and support.

This field is dominated by the iNGOs, religious institutions, and states. But we have the talent and the expertise, and we frankly cannot wait for an organisation like MSF to get its act together and be on the right side of history in the 21st century. So is it not time we form our own indigenous medical humanitarian organisation?

Yazan Al-Saadi is an analyst, writer, editor, and researcher with over 10 years of experience in social research alongside communications and reporting.

Join the conversation: @The_NewArab

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News