Lebanon will need more than social distancing and lockdown to beat coronavirus

In recent months, Lebanon has witnessed unprecedented protests. People have taken to the streets, occupying central spaces in Lebanon's cities and rural towns. Tirelessly, they have chanted slogans decrying the political culture of patronage and corruption that has reigned supreme.

At the heart of their grievances lies the bitter realisation that Lebanon's public policy in terms of providing services and sustainable livelihoods to the general populace is non-existent.

Although the former Saad el-Hariri government resigned almost 10 days after the onset of the protests, it was not possible to obtain concessions from the political elite who clung steadfastly to power.

Many of them argued that a political vacuum would only lead to reigniting tensions and sectarian strife. Within this climate, under the pretext of preventing an economic crash, banks have imposed painful capital controls, hampering depositors' access to their money.

In the last months, new forms of precarity have emerged. People have lost their jobs and experienced layoffs. Firms and restaurants have closed. Students have been unable to pay their tuition fees.

With the formation of Lebanon's new government in January 2020, policy debates have centered on whether and if so, how Lebanon can survive its worst economic crisis.

Vociferous debate over whether the indebted country should solicit IMF aid have brought existing divisions among Lebanon's leaders into the open. On 9 March, for the first time in the country's history, the government defaulted on Lebanon's massive debt. Negotiations with creditors have not yet started, and, amid uncertainty, citizens are deeply concerned about their livelihoods.

|

The coronavirus outbreak is happening against a backdrop of weakened social immunity to upheaval |  |

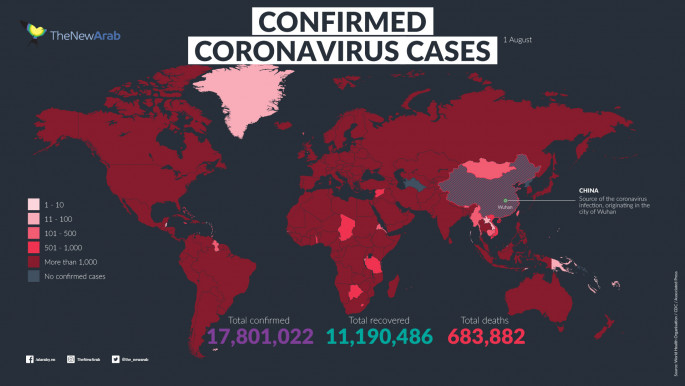

Against this backdrop, the outbreak of the coronavirus has left Lebanon's citizenry battling various forms of vulnerability. On 21 February, the first case of Coronavirus linked to the return of a plane from the city of Qom in Iran was announced.

Speculation was rife that the outbreak would be quickly contained. Soon, however, Lebanon announced that the disease was spreading among the population. Currently, the virus has sickened more than 380 people. The government rushed to declare a state of health emergency. While it initially suspended flights from high risk countries, it ordered on 16 March a two-week lockdown that has been renewed until April 12.

The Lebanese government claims to have acted more swiftly than western governments that have in some cases mulled over lockdowns and border closures. Still, the government's so-called swift decisions need to be situated in Lebanon's broader policy context that has recurrently experienced "governance voids".

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

In fact, the government's response to the pandemic can be described as operational rather than substantive. It is likely to be of little effectiveness in combating the long-term repercussions of the spread of the virus. Here's why.

Absent policy cycles

Policies are most efficient when they undergo a multipronged framework involving drafting, implementation and assessment.

Lebanon's policymaking frame has been characterised by incoherence and "strategic ambiguity". Government policies in fields such as health, infrastructure, economy and refugee displacement have conformed to the logic of "deliberate inaction".

Most importantly, research shows that discussions over security and geopolitical entanglements have dominated formal institutions. Minimal attention has been paid to the politics of citizen wellbeing.

Squabbling in policymaking spheres means the public health sector has been neglected. It is no exaggeration to say that there has been no nation-wide policymaking frame to consolidate the capacity of governmental hospitals and address citizen healthcare.

|

Lebanon's policymaking frame has been characterised by incoherence and 'strategic ambiguity' |  |

With widespread displacement from Syria, international actors such as the European Union have allocated funding through initiatives such as the 2016 EU-Lebanon Compact to improve health services to both refugee and host populations. Yet such initiatives remain limited and, most importantly, externally induced.

It is true that Lebanon is known for its eminent private hospitals that represent more than 80 percent of the country's healthcare capacity. Nevertheless, curtailed capacity to import medical supplies in the context of the dollar shortage has dealt a blow to the health sector. Doctors and nurses have incessantly warned the government that, in such dire circumstances, hospitals would be in no position to respond to health emergencies.

A shallow response to a massively disruptive pandemic

As noted, the newly formed Hassan Diab government posits that it has taken rash decisions in comparison to other countries. It ordered universities and schools to close as early as the beginning of March. It also called upon citizens to observe extreme social distancing as soon as coronavirus started spreading. Many firms have since then called on their employees to work from home.

Theoretically, this seems like Lebanon would be able to carry business as usual amid a coronavirus shutdown. In practice, not everybody has the luxury of a home office, and Lebanon's economy is ill-prepared to deal with the outbreak.

Read more: Beirut under quarantine: Why decades of unshackled neoliberalism left Lebanon in extreme danger from coronavirus

Traders and vendors, especially in poorer and vulnerable areas, have insisted that they needed to keep their shops and markets open. In some cities, municipalities failed to enforce an order of social distancing as people have prioritized their livelihoods in crowded markets.

Additionally, medical experts have stressed that in order to contain the outbreak, it is not enough to ask people to resort to confinement. Aggressive testing and contact tracing to track people who have been exposed to those infected with the virus would need to be applied.

There is significant doubt over whether the government has infrastructural capacity to coordinate the operational aspects of such tasks. Some experts have suggested that political parties' paramedical wings as well as municipal crisis units assume such responsibilities.

|

It's not enough to ask people to resort to confinement |  |

In practice, such tasks are not anchored in the mandate of these local actors. This begs the question as to whether Lebanon's centralised institutions are equipped to develop a sustainable strategy to circumvent the outbreak.

The missing link: citizens and the politics of wellbeing

To understand Lebanon's capacity to contain the outbreak, we also need to factor in citizens' ability to respond to adversity. In the last months, people have lost some of their capacity "to bounce back" from crises. Also, their trust in the political establishment has been further eroded.

It is well documented that citizens thrive best in political systems that account for people's happiness levels. In the context of political indifference, atrophied safety nets, and harsh capital controls, psychologists have warned that citizens have lost much of their "resilience".

Here, psychological coping mechanisms are key to confronting disruptive events such as pandemics. Indeed, the coronavirus outbreak is happening against a backdrop of weakened social immunity to upheaval.

Lebanon's situation is no exception. Currently, all states feel vulnerable in the face of the pandemic. Yet Lebanon has much to say about the predicament of societies facing such outbreaks ill-prepared and grappling with pre-existing fatigue. The Lebanese case also highlights the importance of designing long-term policy cycles in which governments prioritise citizen wellbeing. Facing a global pandemic requires more than confinement and lockdowns.

Tamirace Fakhoury is associate Professor of Political Science and director of the Institute of Social Justice and Conflict Resolution, Lebanese American University.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News