Lebanon needs an independent cabinet with legislative authority

Comment: Researchers at the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies take an in-depth look at how a Lebanese cabinet backed up with real legislative authority would help address Lebanon's multiple crises.

9 min read

The deadly Beirut explosion reiterates Lebanon's need for an independent government [Getty]

In the wake of the August 4, 2020 explosion in Beirut, public pressure and elite-level conflict forced the cabinet of Prime Minister Hassan Diab to resign.

Many factors led to its unsuccessful tenure in mitigating any of the country's multiple and deepening crises. It lacked independence from party elites, who in turn constrained its political space to maneuver. In addition, parliament on several occasions intervened to obstruct the work of the cabinet so as to preserve the interests of political elites.

A cabinet resignation, however, is no guarantee of anything beyond "business as usual" in Lebanese politics. In the search for a new political settlement, several political parties and foreign governments now favor a "national unity government" that would include members of all major political factions. The alleged inclusiveness of this type of cabinet is supposed to ensure political consensus and thereby increase the likelihood of reforms passing through parliament.

Such a government, however, would only worsen Lebanon's malaise. It is precisely the collusion between these parties and their division of state power, public resources, and other privileges of rule that are largely responsible for the harm, suffering, and frustration among so many Lebanese since the end of the civil war (1975–90).

This same set of parties and the political system they created also facilitated the explosion of the Beirut port and the destruction of almost half of the capital. A unity government would suffer from low public acceptance - a public which has spent months on the streets to demand a transition toward a more accountable, transparent, and responsive political and economic system.

Lebanon's many pressing and overlapping crises today require an independent government, made up of competent women and men who share a common vision for leading the country forward. To be effective, this government must also be endowed with legislative powers. Cabinets with these powers are conferred by parliament the right to issue decrees with legislative force for a well-defined set of issue areas, specifically addressing the immediate crisis in question.

Such a government would enable a break from those political actors that have steered the country into the malaise. It could also quickly and effectively execute significant policies and reforms that allow for mitigating the crises and facilitate the transition into an accountable and transparent state that is responsive to its citizens and responsible toward the refugee, migrant labour, and other non-citizen communities in Lebanon. Without such power, any new government - no matter how independent - will fall prey to the political interventions of elites that use the parliament as an anchor for the preservation of the status-quo.

Read more: Beirut blast: 2,750 tonnes of government negligence

Most parliamentary blocs, however, will unlikely accept an independent, competent, and empowered cabinet. After all, such a government would threaten their own interests and potentially their political survival. Yet, a potential renewal of mass protests and other forms of popular mobilisation with such a cabinet as a key demand could pressure dominant political parties to make room for a truly independent government with specific legislative authority.

Also important is that the international community take stock of their complicity in subsidising the reproduction of the status-quo, and cease their support for the parties that make up the political elite.

Moreover, Lebanon is no stranger to governments with legislative authority, at least prior to the Taif Accord. Political elites resorted to such government precisely to circumvent political conflict and procedural gridlocks which were preventing quick and effective responses to crises. The first such cabinet with legislative powers was the independence cabinet of Riad al-Solh (September 1943 – January 1945), empowered in 1944 to create the institutional frameworks for taking over the Common Interests from the French Mandate. Between 1952 and 1988, Lebanon's parliament empowered seven governments with significantly broader legislative authority.

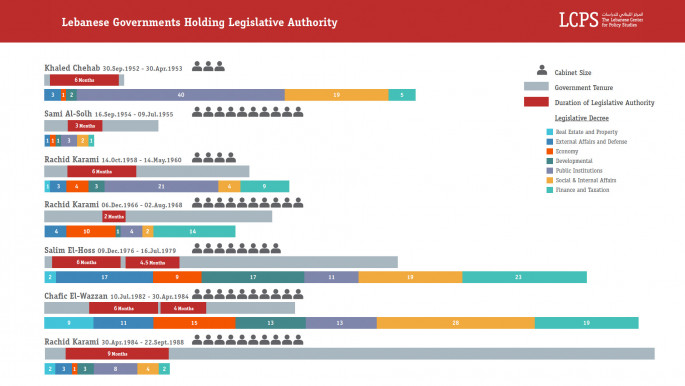

The legislative prerogatives of these seven governments varied in length and lasted from two short months to as long as nine months. In all cases, parliaments endowed governments with legislative authority in a specified range of policy areas, particularly the creation, reorganization, and/or abolition of public institutions.

Most frequently, these governments had legislative authority on issues of the economy, development, finance and taxation, and social and internal affairs. These instances combined produced over 350 legislative decrees, averaging 50 legislative decrees per government. Such cabinet legislative authority reflected a desire for rapid and confidence-creating reforms that were in some ways responsive to the demands of popular mobilisations and/or necessary for the arresting of crises.

While the overall efficacy of these instances reflected the persistence of dominant interests, many of the reforms instituted highlight the potential for legislative prerogatives to introduce meaningful political change.

Figure 1: Size, tenure, duration, and type of legislative decrees produced by governments with legislative authority

For instance, the first electoral law that guaranteed women suffrage, which had been long rejected by successive parliaments, was passed in the form of a legislative decree during the Khaled Chehab government (September 1952 – April 1953). Despite repeated lobbying efforts and public debates, Lebanese women had consistently been denied suffrage since the creation of the state. This was never a constitutional exclusion, but one that was the direct result of various electoral laws that governed successive parliamentary (and, until 1952, municipal) elections.

In the face of a focused women-led suffrage campaign, the Chehab cabinet first issued an electoral law that granted "educated women" the right to vote in the following 1953 parliamentary elections.

Refusing such an exception, the women's movement pressed on - along with their political allies - and eventually pressured the Chehab government to amend the electoral law. The result was that Lebanese women were able to vote and run in parliamentary elections for the first time and consistently since then.

Read more: Lebanon's lost generation grapples with a bleak future

In another instance, a cabinet with legislative authority was able to swiftly act to restore confidence in the economy and prevent a financial crisis. This authorization took place during the June 1967 Arab-Israeli war, and specified "economic and financial matters" as well as "public safety and internal security".

As the outbreak of the war created panic among depositors, Rachid Karami's government (December 1966 - August 1968) swiftly introduced a capital control law to prevent a run on the banks and abrogated it as soon as it was safe to do so.

To address the impact of the first two years of the civil war, also known as the Two-Year War, the Salim El-Hoss cabinet (December 1976 - July 1979) was twice empowered with legislative authority. It enacted several laws that led to long-lasting institutional changes. The scope of its legislative authority covered "reconstructing the country" and "developing and organizing the financial, economic, social, security, defense, information, and educational affairs".

It was in this context that his cabinet passed both a new municipal law in 1977 (the same law that serves as the basis of Lebanon's municipal system until today) and created the first incarnation of the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR).

While all seven governments with such powers differed in terms of the scope of legislative authority, the number of legislative decrees issued and their distribution across policy areas, all of them were empowered in the wake of major crises: The 1952 resignation of President Bechara El-Khoury; the 1958 rebellion; the 1967 Arab-Israeli War; the Two-Year War (1975–76) of the Lebanese civil war; the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon; and the 1984 collapse of the Lebanese lira.

Certainly, not all those policies and changes were individually or collectively reflective of the aspirations and needs of the majority of the population. However, these examples and the broader history they are drawn from highlight two major outcomes of empowered governments.

First, in each decade after independence, Lebanon’s parliaments (with the support of their contemporary presidents) did empower cabinets with legislative authority to rapidly address political, economic, and/or social crises. Empowered governments were exceptions, but they are by no means a novelty in Lebanese political history.

Second, these instances allowed cabinets to mitigate crises and/or introduce institutional and structural change. By being able to enact policies that had the force of law, they generally succeeded in preventing a continuous downward spiral.

Given the unprecedented political, economic, and social crises facing the country, there is today an urgent need for a competent, and empowered cabinet to take shape that can act independently from the traditional political parties.

Several progressive and independent opposition figures and groups are already debating the makeup of such a competent and independent cabinet. Without legislative authority, even the most competent and independent government will fail to champion the changes needed for abetting Lebanon's multiple intensifying crises.

Lebanon's history of empowered governments gives insights into what such a government could achieve. Such powers could include the prerogatives for the government to design and institute a new electoral law as well as empower an electoral commission so that the next election is administered on fair grounds and opens opportunities for political transition.

Moreover, it could allow for addressing the fiscal, monetary, banking, and currency crises, through both a forensic audit of all potentially implicated institutions as well as a capital control law and other stop-gap measures until there is enough information to put forward a medium-to-long-term plan to address and move beyond these crises.

Furthermore, a cabinet empowered with legislative authority could enact a centralized government response to the explosion. This would include search and rescue efforts, the provisioning of medical and other forms of aid to those in need, and the establishment of a transparent and accountable mechanism for investigating the various factors the led to the port explosion and the identification of those responsible. This is to say nothing of a centralized and meaningful response to the Covid-19 pandemic, which has reached crisis proportions in Lebanon.

As in the past, an empowered government could use its prerogatives to set the agenda for instituting longer-term and sustainable institutional change. It could institute the right of Lebanese women to transfer their citizenship to their children in the same way Lebanese men currently do. This would only be one of the many reforms that feminists have long demanded, but it would set an important precedent.

Finally, a cabinet empowered with legislative authority could enact the judicial reforms necessary to make the judiciary a truly independent institution, which in turn is a necessary correlate to holding all individuals and collective actors in Lebanon, whether public or private, accountable for their conduct in elections, the economy, the explosion, and much more.

Ziad Abu-Rish is Co-Director of the MA Program in Human Rights and the Arts and Visiting Associate Professor of Human Rights at Bard College, and Lebanese Center for Policy Studies (LCPS) fellow. Follow him on Twitter: @ziadaburish

Sami Atallah is the excecutive director of LCPS. Follow him on Twitter: @samiatallah1

Mounir Mahmalat is a senior researcher at LCPS and consultant for the World Bank.

Wassim Maktabi is a public policy researcher at LCPS.

This article is republished with permission from the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Many factors led to its unsuccessful tenure in mitigating any of the country's multiple and deepening crises. It lacked independence from party elites, who in turn constrained its political space to maneuver. In addition, parliament on several occasions intervened to obstruct the work of the cabinet so as to preserve the interests of political elites.

A cabinet resignation, however, is no guarantee of anything beyond "business as usual" in Lebanese politics. In the search for a new political settlement, several political parties and foreign governments now favor a "national unity government" that would include members of all major political factions. The alleged inclusiveness of this type of cabinet is supposed to ensure political consensus and thereby increase the likelihood of reforms passing through parliament.

Such a government, however, would only worsen Lebanon's malaise. It is precisely the collusion between these parties and their division of state power, public resources, and other privileges of rule that are largely responsible for the harm, suffering, and frustration among so many Lebanese since the end of the civil war (1975–90).

This same set of parties and the political system they created also facilitated the explosion of the Beirut port and the destruction of almost half of the capital. A unity government would suffer from low public acceptance - a public which has spent months on the streets to demand a transition toward a more accountable, transparent, and responsive political and economic system.

Lebanon's many pressing and overlapping crises today require an independent government, made up of competent women and men who share a common vision for leading the country forward. To be effective, this government must also be endowed with legislative powers. Cabinets with these powers are conferred by parliament the right to issue decrees with legislative force for a well-defined set of issue areas, specifically addressing the immediate crisis in question.

Twitter Post

|

Such a government would enable a break from those political actors that have steered the country into the malaise. It could also quickly and effectively execute significant policies and reforms that allow for mitigating the crises and facilitate the transition into an accountable and transparent state that is responsive to its citizens and responsible toward the refugee, migrant labour, and other non-citizen communities in Lebanon. Without such power, any new government - no matter how independent - will fall prey to the political interventions of elites that use the parliament as an anchor for the preservation of the status-quo.

Read more: Beirut blast: 2,750 tonnes of government negligence

Most parliamentary blocs, however, will unlikely accept an independent, competent, and empowered cabinet. After all, such a government would threaten their own interests and potentially their political survival. Yet, a potential renewal of mass protests and other forms of popular mobilisation with such a cabinet as a key demand could pressure dominant political parties to make room for a truly independent government with specific legislative authority.

Also important is that the international community take stock of their complicity in subsidising the reproduction of the status-quo, and cease their support for the parties that make up the political elite.

Moreover, Lebanon is no stranger to governments with legislative authority, at least prior to the Taif Accord. Political elites resorted to such government precisely to circumvent political conflict and procedural gridlocks which were preventing quick and effective responses to crises. The first such cabinet with legislative powers was the independence cabinet of Riad al-Solh (September 1943 – January 1945), empowered in 1944 to create the institutional frameworks for taking over the Common Interests from the French Mandate. Between 1952 and 1988, Lebanon's parliament empowered seven governments with significantly broader legislative authority.

The legislative prerogatives of these seven governments varied in length and lasted from two short months to as long as nine months. In all cases, parliaments endowed governments with legislative authority in a specified range of policy areas, particularly the creation, reorganization, and/or abolition of public institutions.

Most frequently, these governments had legislative authority on issues of the economy, development, finance and taxation, and social and internal affairs. These instances combined produced over 350 legislative decrees, averaging 50 legislative decrees per government. Such cabinet legislative authority reflected a desire for rapid and confidence-creating reforms that were in some ways responsive to the demands of popular mobilisations and/or necessary for the arresting of crises.

While the overall efficacy of these instances reflected the persistence of dominant interests, many of the reforms instituted highlight the potential for legislative prerogatives to introduce meaningful political change.

Figure 1: Size, tenure, duration, and type of legislative decrees produced by governments with legislative authority

|

|

| Click to enlarge [LCPS] |

For instance, the first electoral law that guaranteed women suffrage, which had been long rejected by successive parliaments, was passed in the form of a legislative decree during the Khaled Chehab government (September 1952 – April 1953). Despite repeated lobbying efforts and public debates, Lebanese women had consistently been denied suffrage since the creation of the state. This was never a constitutional exclusion, but one that was the direct result of various electoral laws that governed successive parliamentary (and, until 1952, municipal) elections.

In the face of a focused women-led suffrage campaign, the Chehab cabinet first issued an electoral law that granted "educated women" the right to vote in the following 1953 parliamentary elections.

Refusing such an exception, the women's movement pressed on - along with their political allies - and eventually pressured the Chehab government to amend the electoral law. The result was that Lebanese women were able to vote and run in parliamentary elections for the first time and consistently since then.

Read more: Lebanon's lost generation grapples with a bleak future

In another instance, a cabinet with legislative authority was able to swiftly act to restore confidence in the economy and prevent a financial crisis. This authorization took place during the June 1967 Arab-Israeli war, and specified "economic and financial matters" as well as "public safety and internal security".

As the outbreak of the war created panic among depositors, Rachid Karami's government (December 1966 - August 1968) swiftly introduced a capital control law to prevent a run on the banks and abrogated it as soon as it was safe to do so.

To address the impact of the first two years of the civil war, also known as the Two-Year War, the Salim El-Hoss cabinet (December 1976 - July 1979) was twice empowered with legislative authority. It enacted several laws that led to long-lasting institutional changes. The scope of its legislative authority covered "reconstructing the country" and "developing and organizing the financial, economic, social, security, defense, information, and educational affairs".

Twitter Post

|

It was in this context that his cabinet passed both a new municipal law in 1977 (the same law that serves as the basis of Lebanon's municipal system until today) and created the first incarnation of the Council for Development and Reconstruction (CDR).

While all seven governments with such powers differed in terms of the scope of legislative authority, the number of legislative decrees issued and their distribution across policy areas, all of them were empowered in the wake of major crises: The 1952 resignation of President Bechara El-Khoury; the 1958 rebellion; the 1967 Arab-Israeli War; the Two-Year War (1975–76) of the Lebanese civil war; the 1982 Israeli invasion of Lebanon; and the 1984 collapse of the Lebanese lira.

Certainly, not all those policies and changes were individually or collectively reflective of the aspirations and needs of the majority of the population. However, these examples and the broader history they are drawn from highlight two major outcomes of empowered governments.

First, in each decade after independence, Lebanon’s parliaments (with the support of their contemporary presidents) did empower cabinets with legislative authority to rapidly address political, economic, and/or social crises. Empowered governments were exceptions, but they are by no means a novelty in Lebanese political history.

Second, these instances allowed cabinets to mitigate crises and/or introduce institutional and structural change. By being able to enact policies that had the force of law, they generally succeeded in preventing a continuous downward spiral.

Given the unprecedented political, economic, and social crises facing the country, there is today an urgent need for a competent, and empowered cabinet to take shape that can act independently from the traditional political parties.

Several progressive and independent opposition figures and groups are already debating the makeup of such a competent and independent cabinet. Without legislative authority, even the most competent and independent government will fail to champion the changes needed for abetting Lebanon's multiple intensifying crises.

Lebanon's history of empowered governments gives insights into what such a government could achieve. Such powers could include the prerogatives for the government to design and institute a new electoral law as well as empower an electoral commission so that the next election is administered on fair grounds and opens opportunities for political transition.

|

Without legislative authority, even the most competent and independent government will fail to champion the changes needed |  |

Furthermore, a cabinet empowered with legislative authority could enact a centralized government response to the explosion. This would include search and rescue efforts, the provisioning of medical and other forms of aid to those in need, and the establishment of a transparent and accountable mechanism for investigating the various factors the led to the port explosion and the identification of those responsible. This is to say nothing of a centralized and meaningful response to the Covid-19 pandemic, which has reached crisis proportions in Lebanon.

As in the past, an empowered government could use its prerogatives to set the agenda for instituting longer-term and sustainable institutional change. It could institute the right of Lebanese women to transfer their citizenship to their children in the same way Lebanese men currently do. This would only be one of the many reforms that feminists have long demanded, but it would set an important precedent.

Finally, a cabinet empowered with legislative authority could enact the judicial reforms necessary to make the judiciary a truly independent institution, which in turn is a necessary correlate to holding all individuals and collective actors in Lebanon, whether public or private, accountable for their conduct in elections, the economy, the explosion, and much more.

Ziad Abu-Rish is Co-Director of the MA Program in Human Rights and the Arts and Visiting Associate Professor of Human Rights at Bard College, and Lebanese Center for Policy Studies (LCPS) fellow. Follow him on Twitter: @ziadaburish

Sami Atallah is the excecutive director of LCPS. Follow him on Twitter: @samiatallah1

Mounir Mahmalat is a senior researcher at LCPS and consultant for the World Bank.

Wassim Maktabi is a public policy researcher at LCPS.

This article is republished with permission from the Lebanese Center for Policy Studies.

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News