How coronavirus presented China with a dream opportunity for surveillance

But when a crisis settles in, and becomes routine, tyrannies can always be counted upon to capitalise somehow. They can turn the very worst that befalls a people to the state's advantage.

And so China has responded to the coronavirus pandemic. Not with openness and a desire to cooperate, but with obfuscation and bluster, continued obstinacy on Taiwanese membership of world institutions, and more besides.

But perhaps most dangerously, the pandemic has afforded the Chinese state a dream opportunity: a chance to extend its reach and intensify its grip on China's people, most visible in a new drive towards state surveillance.

Public health demands knowledge of the public. This is something both authoritarian democratic countries have now decided. Many nations have begun to trial software and practical apparatus designed to keep tabs on the movement and interaction of people, all the better to erect digital 'cordons sanitaires' around the ill and infectious, and to keep outbreaks and newly emerging clusters under control.

Those who campaign for privacy have expressed disquiet across the board.

But in China, the infrastructure of supervision and control pioneered in suppression of minorities disliked by the state is becoming more and more widespread.

|

When a crisis settles in, and becomes routine, tyrannies can always be counted upon to capitalise somehow |  |

The Chinese state has begun to introduce a new system of cameras to monitor the movements of the population, including outside people's front doors and, potentially, within their homes. This could mean more than an interruption of private life in keeping with exceptional times.

It might signal the moment the Chinese state decided all pretence was off, and the moment to institute day-round, endless supervision of the population had come.

The Chinese state has responded to the virus in a remarkable way. Separating outright deceit and propaganda from the reality of matters is difficult. But regardless of its claims of success, the state in China has implemented a highly interventionist policy.

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

Its officials take temperatures almost incessantly. They demand that people isolate themselves when apparently symptomatic, and actively separate out those who might carry the virus from the rest of the population. People are placed in convalescent hospitals whether they have a severe case of the disease or not.

These interruptions to ordinary life seem invasive but largely benign. But those measures that follow this aggressively interventionist approach may prove rather more worrying.

The cameras most notably. In Xinjiang, where the system was pioneered, there are cameras "everywhere, on the street corner, inside every building", according to one approving local interviewed last year by the Financial Times. He suggested that there was no crime; there was no place for it to hide. But that is not the sole point of this system of surveillance.

|

These cameras keep the Uighur minority under constant watch |  |

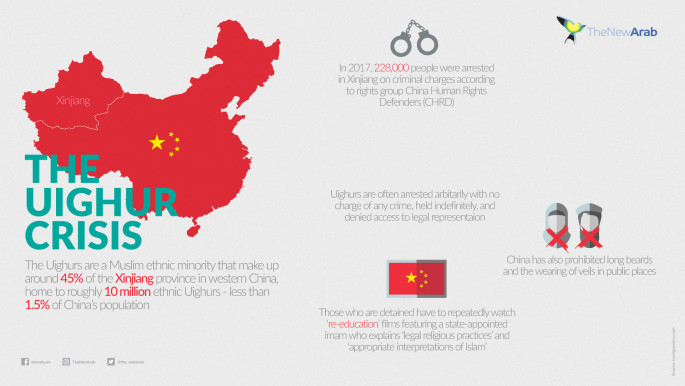

These cameras keep the Uighur minority under constant watch. It is the most obvious and intrusive aspect of a broader Chinese campaign against Uighurs which includes increased observation, widespread cultural suppression, and ends with mass prison camps and forced labour.

But it all begins with surveillance, constant and relentless, a background to and example of the Chinese state's mistreatment of a minority it deems undesirable.

In trying to stop the spread of the virus, most countries have had to reach into a box of tricks they would rather not deploy. They have locked down their citizens, often on pain of fines or even imprisonment. They have mandated the wearing of masks. They have closed schools and bars, restaurants and gyms, and banned large gatherings.

Some countries have witnessed government overreach as the scope of the crisis became clear, but to differing extents.

Twitter Post

|

Hungary has seen its far-right prime minister, Viktor Orban, extend his own power to rule by decree - to the chagrin of his European Union neighbours, and some muted international condemnation.

For a time, before the formation of a new government could be agreed, Israel's prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and his caretaker cabinet operated without the say-so of the parliament, and acted to divert efforts to try him for corruption.

Read more: How much of your stuff is linked to forced Uighur labour?

The county has also implemented strenuous conditions to its lockdown, and has directed some of the technology used for counterterrorism and national security inward, to monitor the disease's spread among the population.

Whether Israel, Hungary and other countries resume 'ordinary' government any moment soon remains in question. Many nations have passed sweeping legislation designed to smooth the path of economic stimulus, and to effect the commandeering of national resources and the redirection of manufacturing to fill orders of medical necessity.

But China has gone yet further than all of them. Its box of tricks is capacious, and its apparatus is well-practised in using the tools at its disposal to monitor, to suppress, and to harass those the state consider threats to the Communist Party's plan for the nation.

In many countries there is vigorous discussion about the creeping authoritarianism that responding to the virus might incentivise and reward.

And there is some talk among expatriates in China about whether a new network of cameras is legal. But it will do little good. Rather significantly, these discussions miss the fact that the Chinese state can do whatever it likes.

It can only be a concern that some of those tools which once saw special use in victimising a minority are now taking their place as a feature of uniform national policy. It is a singularly worrying prospect.

James Snell is a writer whose work has appeared in numerous international publications including The Telegraph, Prospect, National Review, NOW News, Middle East Eye and History Today.

Follow him on Twitter: @James_P_Snell

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News