How Abu Dhabi is helping out Damascus

Two weeks later, Middle East Eye revealed the terms of an agreement between the leader of the UAE and his Syrian counterpart. The report claims that MBZ offered Assad $3 billion in exchange for a resumption of fighting in Idlib, the Syrian province bordering Turkey, where a fragile cease-fire has been in place since an accord between Ankara and Moscow on 6 March 2020.

The financial aid from Abu Dhabi, if confirmed, would be welcome: the Syrian regime's major sponsors, Iran and Russia, have been bled dry.

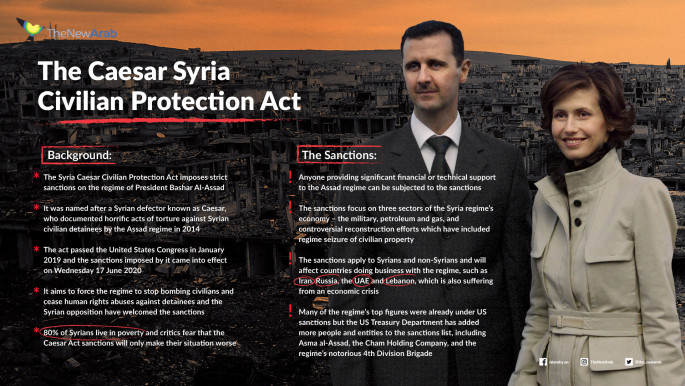

Washington has been leaning on its allies in the Gulf, as well as on Egypt, to attempt to dissuade them from following the example of Abu Dhabi and normalising relations with the Syrian regime. On 20 December 2019, the US Congress passed the Caesar Act, imposing sanctions on any institution or person doing business with Damascus. It entered into law on 1 June.

This ruffled no feathers in Abu Dhabi. On 3 December 2019, while the Caesar Act was being debated, the UAE's chargé d'affaires for Damascus, Abdul Hakim Al-Nuaimi, was celebrating "the close connections between the two countries." The UAE has, however, held back from naming an Ambassador to Syria, making do with a chargé d'affaires, presumably to avoid provoking its US ally.

Civil and military aid

Since the re-opening of its embassy in Damascus at the end of 2018, Abu Dhabi has provided food and medical aid to hospitals in areas controlled by the Syrian regime. An Emirati delegation flew to Syria in the autumn of 2017 to familarise itself with the situation on the ground and evaluate reconstruction and development needs.

Our sources also indicate that the UAE had already financed the reconstruction of public buildings, power stations and the Syrian capital's water network. The Emirates, known affectionately as the "Little Sparta" by Trump's former Secretary of State for Defence and former military adviser to MBZ, James Mattis, is also said to have provided military assistance to Syria.

|

Abu Dhabi is also providing technical, scientific and logistical training to managers in the Syrian military intelligence services |  |

A helicopter and fighter pilot, alumnus of the British military training college Sandhurst, Mohammed bin Zayed has turned his country into the third biggest arms importer in the world, while also nurturing the development of a national armaments industry. The UAE houses around 170 companies manufacturing light armaments, guided missiles, drones, all-terrain vehicles and warships.

A British diplomat described the Emirati army as "disciplined, extremely strategically and logistically effective despite its small size, and distinct from the Saudi Arabian forces [through its efficacy] in the Yemen war."

The sources refer, without specifying dates, to a visit to Syria made by eight Emirati army officers, to share their expertise with high-ranking figures in the Syrian army, as well as to five Syrian pilots being sent to improve their skills at the Khalifa Ben Zayed Air College (KBZAC) military academy in Al-Aïn, west of Abu Dhabi.

Secret services training

Abu Dhabi is also providing technical, scientific and logistical training to managers in the Syrian military intelligence services. The training courses, provided by different bodies scattered across the Emirates, began on 15 January 2020 and last between two and 12 months, depending on their content.

Thirty-one non-commissioned officers and eight civil computer science engineers are being trained, principally in information and communication systems, information security and networks. They are supervised by four Syrian intelligence service officers, including Colonel Zulficar Wassouf, the head of intelligence services training, and Lieutenant-Colonel Jihad Barakat, cousin of the Syrian president.

|

|

| [Click to enlarge] |

Having it both ways

The Syrian uprising was initially seen by Abu Dhabi as a chance to uncouple Syria from its powerful ally, Iran, enemy of certain Gulf monarchies. It expressed support for the protesters and, when the peaceful revolution tipped into armed struggle, offered financial and military aid to the rebels. According to the NGO Spin Watch, between 2012 and 2014 the British public relations company Quiller Consultants was contracted to promote the cause of the Free Syrian Army (FSL) in the UK. The consultancy fee was paid by the Embassy of the UAE in London. The project was managed by Lana Nusseibeh, a high-ranking Emirates diplomat, and by the UAE's Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Anwar Gargash, who remains in the post.

During the same period, however, the UAE was providing fuel to the Syrian army, in violation of the US and EU embargo. Syria had been under sanctions since the summer of 2011, because of its repression of the then peaceful protests. In 2014 the US Treasury announced the inclusion of the Emirates oil company Pangates International Corporation, based in the Emirate of Sharjah, on its list of sanctioned bodies, suspecting it of providing fuel to Syrian military aviation.

The sanctions also dictated the freezing of financial assets of people close to the regime. Some of these turned to another Emirate to shelter their fortunes, that of Dubai. Although diplomatic relations between Syria and the UAE had officially been cut off, the Emir of Dubai, Sheikh Mohamed Bin Rashid al-Maktoum, did not object to the installation in his domain of the sister and mother of the Syrian president.

|

This re-integration is now contested by few Arab countries, but its momentum has yet to influence western powers |  |

Bushra al-Assad moved to the emirate in 2012, shortly after the assassination of her husband Assef Shawkat, the Assistant Director of Military Intelligence. Her relationship with the local authorities were so cordial that she was rumoured to have entered into a secret marriage with Dubai's Police Commander, Dahi Khalfan. The rumour was unfounded, but reflected the level of support given to the widow by the police chief, who defended her when she was refused a Schengen visa.

Known for his plain speaking and his compulsive use of Twitter, where he has more than two million followers, Khalfan has described Bashar al-Assad as a "man endowed with a strong sense of morality".

Rami Makhlouf, the richest man in Syria, a cousin of the Syrian president but now on bad terms with him, had already taken up residence in the emirate before the uprising. His sons Mohamed and Ali regularly make the headlines there for their lavish lifestyles. A symbol of the corruption and nepotism of the Assad family, Makhlouf has fallen out of favour, replaced by a new generation of businessmen making profit from the ruins of war. One of these is Samer Fouz, who lives between Damascus and Dubai and whose political influence over the Syrian president rises in proportion to the growth of his fortune, acquired mainly through the spoils of businesses seized by the state.

Read more: What UAE's Mohammed bin Zayed seeks to gain from the coronavirus crisis

A complex game with the opposition

The US has not terminated relations with the Syrian opposition, or at least not with those elements of it which have made sure to distance themselves from approaches it considers "jihadist". These elements include the Cairo platform, which rejects a military response to the conflict, advocates a political transition and does not demand the resignation of Bashar Al-Assad as a prerequisite to negotiations. Along with the Moscow platform, this political coalition features on the list of opposition groups tolerated by Damascus.

Another important Syrian opposition figure with close links to Abu Dhabi is Ahmad Jarba. Based in Cairo, he represented tribal interests on the Syrian national coalition, and is a member of the cross-border Bedouin tribal confederation, the Shammar, which covers the entire Arabian peninsula. After fleeing Syria in 2012, He settled in Saudi Arabia, where he developed close relationships with the Saudi and Emirates intelligence services.

Twitter Post

|

In 2016 he founded Ghad Al-Soury (Syria's Tomorrow Movement) with the support of Egypt and of MBZ's henchman, the Palestinian Mohammed Dahlan. The organisation's aims are stated as being the promotion of a pluralist, decentralised, secular Syria. Its military wing, the Elite Forces, fought as part of the coalition against Islamic State (IS). Since the defeat of IS its manpower has been greatly reduced.

It is not possible to understand the diplomatic manoeuvres that have taken place in the region without considering the role of Russian president Vladimir Putin. The Kremlin chief appears more than ever to be the real puppet-master of Middle Eastern negotiations. It was Russia's 2013-2018 Ambassador to Abu Dhabi, Alexander Efimov, now in post in Damascus, who was charged by Putin with mediating between MBZ and his Syrian counterpart in the run-up to the re-opening of the UAE Embassy in Syria.

A strategic vision for the region

On the fringes of the Manama Dialogue of December 2017, Anwar Gargash said, "the aim of the UAE in the region is a return to stability, not to the status quo. Those are two different things."

Jalal Harchaoui, geopolitical researcher at the university of The Hague, sees Gargash's declaration as confirmation of "the belief that the Arab leaders who were deposed by the Arab Spring in Tunisia, Yemen and Egypt were toppled because of their weakness." According to the researcher, "to fit this conception of stability, the generation that succeeds these leaders must show its strength through authoritarianism and coercion," like Abdel Fattah al-Sisi.

While the scale of his repression of Egyptian civil society brought President Sisi condemnation from human rights organisations, his policies have pleased the Emirati leader. MBZ honoured Sisi with the highest possible civil distinction, the Order of Zayed, at a ceremony in Abu Dhabi in November 2019.

Egypt, which never broke off diplomatic relations with Syria and maintains a solid security collaboration with it, is one of the most vocal proponents of the return of Damascus to the Arab League. This re-integration is now contested by few Arab countries, but its momentum has yet to influence western powers, which, on the surface at least, still appear hostile to the idea.

Khaled Sid Mohand is a journalist in charge of the investigative division of the CJL.

This article was originally posted in French by our partners Orient XXI.

Join the conversation: @The_NewArab

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News