EU countries have a moral duty to help Afghan refugees

The attitude of European nations towards supporting refugees fleeing Afghanistan since the Taliban's takeover of the country could fool anyone into thinking that they had no hand in the current political crisis.

The last two decades following the invasion of Afghanistan have left a trail of death, instability and destruction in their wake. Unsurprisingly, they have also generated more than some distrust towards the US and its allies - in the UK and across Europe - who justified the war on the basis that it would positively transform the country and uproot terrorism. However, all of this has seemingly disappeared from the public narrative.

Instead, within days of the Taliban victory, European statements about controlling numbers and borders started rolling in. Far from taking responsibility and dealing with the repercussions of imperialist endeavours that have taken the lives of over 100,000 people, western leaders scrambled to close borders and strengthen controls.

"Western leaders scrambled to close borders and strengthen controls"

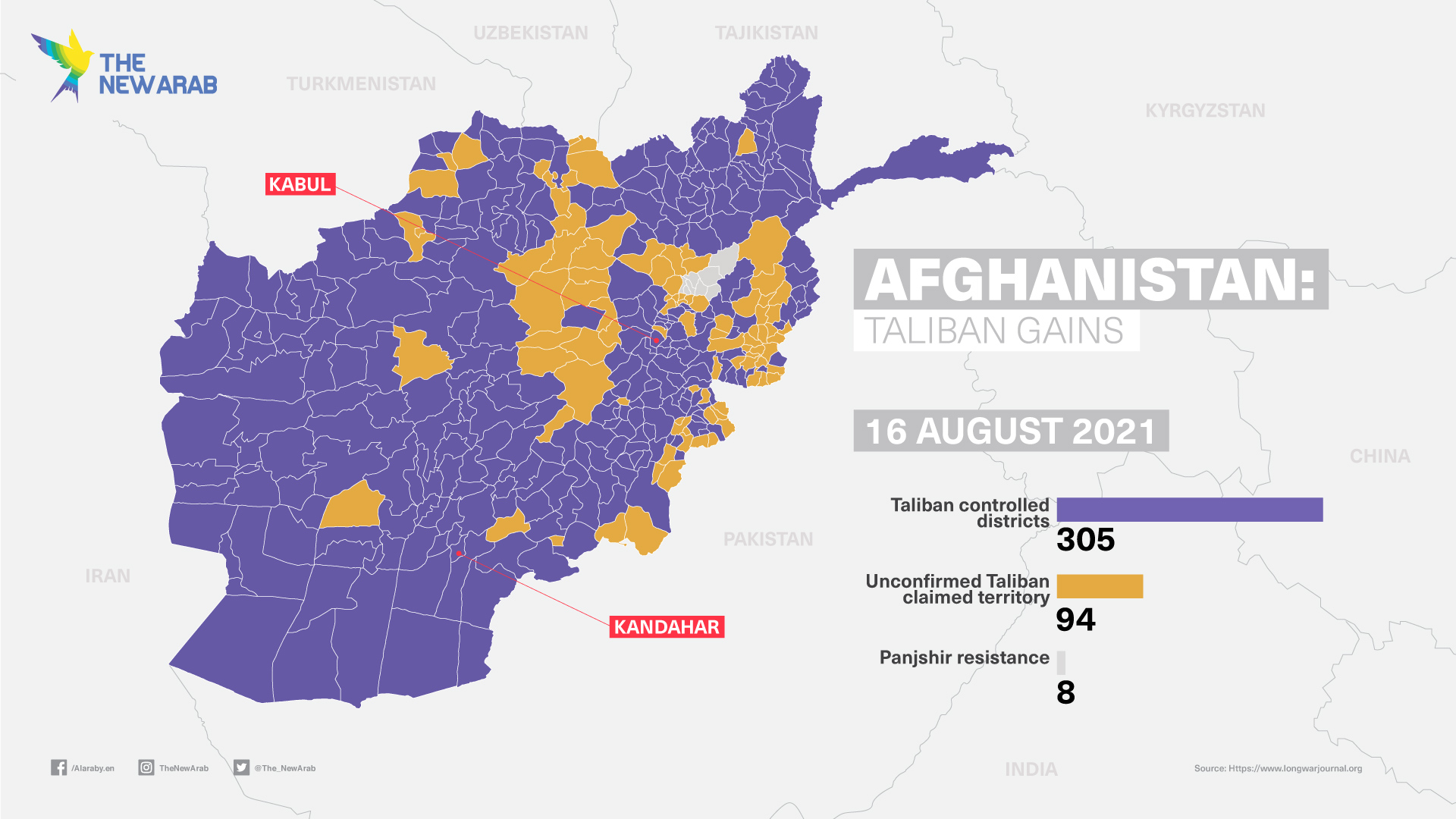

In early August, as the Taliban were quickly gaining ground in the country, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Greece, Germany and the Netherlands had already written to the European Commission calling for deportations of rejected Afghan migrants to continue. "Stopping returns sends the wrong signal and is likely to motivate even more Afghan citizens to leave their home for the EU," they warned.

An obsession with keeping Afghans out of Europe continued after the Taliban took over the capital. French President Emmanuel Macron announced that France, Germany and other EU states were joining forces to deal with the "irregular migratory flows" that world leaders were predicting.

Furthermore, Macron, in a national televised address, wasted no time in making France's priorities clear when he stated that his country should, "anticipate and protect itself from a wave of migrants". He also described the events in Afghanistan as an "important challenge for our own security". The safety of Afghans, on the other hand, received no mention. Nor did over a decade of French military presence in the country.

Even Macron's pledge to support refugees, sounded conditional when he mentioned Afghans who had already been allowed into France who had previously worked with the French army. "It is our duty and our dignity to protect those who help us: interpreters, drivers, cooks and many others."

In other words, the French state is committed to differentiating between the "good migrant" who supports France's military endeavours, and the "bad migrant" who seeks a better life overseas in the country that participated in the destruction of his homeland. The protection afforded to those fleeing now will likely also be dependent on which category they fall into.

To make matters worse, his speech was released just hours after videos and images circulated of Afghans falling from planes that they desperately clung to with the hopes of leaving the country.

This is the level of consideration that Afghans can expect from the French state, and sadly many others across the continent. The care expressed by western leaders further highlights that intervention was hardly motivated by concern for civilians in the first place.

In reality, Afghans have experienced the violence of western borders for the last 20 years. The diaspora has long been ill-treated and discriminated against by Fortress Europe which has criminalised, detained and deported them.

The UK for example has rejected over 32,000 Afghan asylum seekers since the invasion in 2001. Over 600 people who arrived from Afghanistan as unaccompanied minors, were deported by the Home Office between 2009-2015. Foreign Secretary Dominic Raab's statement that Britain has "always been a country that has provided a safe haven for those fleeing persecution" is an empty one.

"In reality, Afghans have experienced the violence of western borders for the last 20 years"

This history also makes the UK government's commitment to accept 20,000 refugees over several years seem paltry. Following the UNHCR's predictions that up to 3.5 million Afghans could be internally displaced, the Johnson government's resettlement plan, which goes as far as stipulating that only 5,000 Afghans will be taken in during the first year of the programme, is clearly woefully inadequate.

The omission of responsibility, shifting of blame, and distancing tactics are likely to continue among the most powerful and complicit nations. Just this week, the G7 meeting chaired by Britain discussed holding the Taliban to account for "their actions on preventing terrorism, on human rights, in particular, those of women, girls and minorities and on pursuing an inclusive political settlement in Afghanistan". No mention was made of their own role in aggravating all of these issues over the last 20 years, however.

"Now is not the time to forget and move on. It is not the moment to close our borders and wait for the storm to pass"

It is therefore imperative that we hold these countries to account in order to pressure them to not only accept but also adequately support Afghan refugees. It is also crucial that the lessons of the war in Afghanistan, which was opposed by millions of anti-war activists around the world, are not swept under the carpet.

Our states do not care about the fate of oppressed people - at home or abroad - their interventions are never guided by humanitarian concerns.

We must also continue campaigning against the so-called War on Terror, which was used to justify the invasion in the first place. Campaigners are already doing this work, some using creative methods to speak truth to power.

One such example is the work being done by BÉZNĂ Theatre. This British-Romanian political theatre group has organised The People's Tribunal on Crimes of Aggression: Afghanistan Sessions. The aim is to mark the 20th year of Britain's involvement in the War on Terror and investigate its role in what many consider to be an illegal occupation. The three-day event "will focus specifically on the 2001 invasion of Afghanistan, where the War on Terror began and where war has not yet stopped", explained creators Sînziana Cojocărescu and Nico Vaccari.

"We have no doubt about the potential theatre has to investigate and expose mechanisms of oppression and violence that affect each and everyone one of us - perhaps the most powerful role that theatre can and should serve is a social-political one."

BÉZNĂ Theatre is showing the way. Now is not the time to forget and move on. It is not the moment to close our borders and wait for the storm to pass. It is the time to hold our leaders and our states accountable and learn the lessons of 20 years of war, destruction, and oppression - in Afghanistan and around the world.

Malia Bouattia is an activist, a former president of the National Union of Students, and co-founder of the Students not Suspects/Educators not Informants Network.

Follow her on Twitter: @MaliaBouattia

Have questions or comments? Email us at: editorial-english@alaraby.co.uk

Opinions expressed here are the author's own, and do not necessarily reflect those of her employer, or of The New Arab and its editorial board or staff.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News