In the wake of Egypt's November 2016 agreement with the IMF to borrow $12 billion, the rate of growth of the country's public debt has dramatically accelerated. By mid-summer local currency denominated public debt had ballooned out to 94 percent of GDP, while the swelling foreign currency debt had reached $67 billion, 35 percent of GDP.

The cost of servicing the ballooning debt has skyrocketed due both to its prodigious size and the high interest rates the Egyptian government has been forced to pay to attract capital. Egypt has borrowed almost 20 percent more domestically in 2017 than in all of 2016.

Treasury bills ranging in maturity from 3 months to one year have attracted up to 20 percent interest throughout 2017. Average yields on the debt have climbed since early 2017 by 84 base points to 17.5 percent.

In contrast, the average for the 31 countries in the Bloomberg Emerging Market Local Sovereign Index saw a rise of only 13 base points to 4.73 percent, about one quarter of the Egyptian rate, far and away the highest on that Index.

|

|

Poor Egypt, in other words, is paying many times what rich Germany, Japan, or the US pay to finance their governments' debts |

|

|

Globally declining interest rates on emerging markets' sovereign foreign debt, dragged down by historically low interest rates for OECD sovereign debt, have also dragged down rates on Egypt's recent Eurobond issues, on the latest of which it paid six percent, compared to some 8 percent previously.

This little bit of good news, however, is offset absolutely by the increased magnitude of the foreign debt; and relatively by the fact that developed economies are paying between zero and two percent on their sovereign debt.

Poor Egypt, in other words, is paying many times what rich Germany, Japan, or the US pay to finance their governments' debts. Moreover, Egypt has to do so in a foreign currency against which the Pound will inevitably devalue over the life of the loans, thereby rendering repayment yet more demanding.

|

|

|

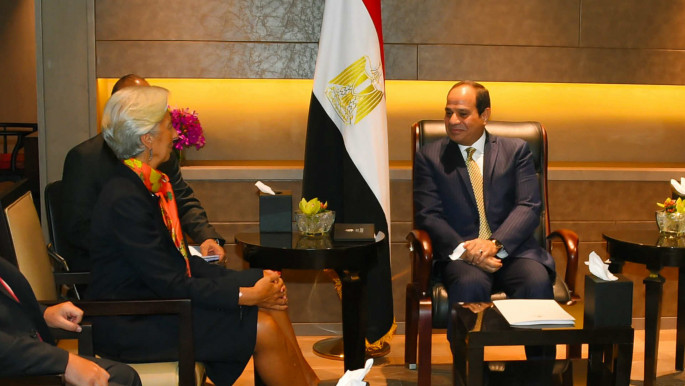

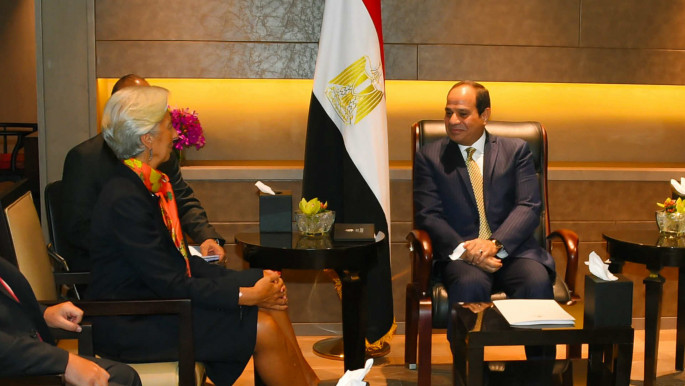

The IMF's chief, LaGarde met Egypt's President Sisi in September

2016 [Anadolu]

|

The burden debt repayment now placed on Egyptian public finances is suggested by its phenomenal rate of growth since 2001, when it absorbed 3.7 percent of government revenue. By 2014 that proportion had grown by almost ten times to 30.7 percent.

Debt servicing now absorbs fully one third of the Egyptian budget. That cost, along with payment of the government wage bill and consumer subsidies, account for more than 90 percent of government expenditures, leaving precious little for capital investment.

Indeed, the proportion of GDP allocated to fixed capital formation has slid below ten percent, one of the world's lowest rates. The comparable figure in several East Asian countries is in excess of 40 percent.

Growing indebtedness has occurred in tandem with stagnating economic growth. The IMF cut its forecast for 2017 growth to 3.5 percent from four percent. One of the causes of slowing growth is high interest rates, which have contributed to a some twenty month continuing slide in private business activity.

Amazingly enough the government of Egypt and some investment bankers have put a favorable spin on these worrying figures. The core of their argument is the willingness of foreign investors to buy into Pound denominated debt. This they have done to the tune of about three percent of new T-bill issues during 2017, as opposed to less than 1 percent in the previous year.

A vote of confidence

This foreign investment, coupled with Egypt's Eurobonds being oversubscribed despite their lower interest rates in 2017, is presented as a two-fold vote of confidence in the Egyptian economy. In reality, the global financial world is starved of high yielding sovereign debt, hence the attractiveness of Egypt's, which is, after all, the world's most lucrative for those investors.

|

|

What is the possibility that Egypt will default? |

|

|

The obvious question is whether or not even at these world leading interest rates risk has been priced in adequately. What is the possibility that Egypt will default?

Unfortunately that prospect is a real one. Debt is being racked up not to develop productive economic capacity, whether physical or human, but almost entirely to pay recurrent expenses. The one exception is military expenditures. In 2016-17 Egypt was the world's fourth largest purchaser of foreign manufactured weapons.

The only economic bright spot is gas production, set to increase substantially at the end of 2017. But that production will be consumed domestically, so generate few direct foreign currency earnings, albeit some indirect ones through exports of energy intensive products like cement.

This raises the question of what the calculations of Egypt's decision makers might be. Are President Sisi and his officer colleagues simply blind to economic realities? Have they convinced themselves that by taking over the economy, the military will greatly increase economic output?

Could they be calculating that they will simply stiff foreign investors in Egyptian sovereign debt because the country will be deemed to be too big and too strategically vital to fail, so will be protected by other sovereigns, ranging from the US to Russia?

Could they be hoping that the Arab Gulf states will again come to the rescue because they will have to depend on Egypt's military might to defend themselves against one another, Iran or terrorism?

Some of these answers obviously suggest wishful thinking. They also reveal a disdain for Egypt's recent history. In the late 1980s Egypt's foreign debt, along with that of many other emerging markets, ballooned out as oil prices dropped and world economic activity slowed. The country was saved by the US-led offer to forgive the bulk of that debt in return for Egypt joining coalition forces assembled to throw Saddam's Iraqi forces out of Kuwait.

The lesson President Mubarak took away from that episode was never again to become beholden to foreign creditors, as they would then dictate Egypt's foreign policy. For the remainder of his presidency he refused to countenance foreign borrowings, relying instead on domestic savings to finance his government.

|

|

If Sisi's calculation is that he can stiff his creditors, he had better think again |

|

|

It is paradoxical, therefore, that President Sisi, who has sought to cultivate an image of independence from the US and other foreign countries, has ignored the hard-earned lesson of his predecessor.

Most probably, the magnitude of the country's economic problems are so great he calculates that he has simply no option but to keep borrowing and spending, lest he be thrown out of power by his people or fellow army officers. And of course indebtedness provides him leverage any heavily indebted borrower has over his lenders.

But Sisi should be wary. History can repeat itself. Khedive Ismail apparently believed when he ran up the country's foreign debt some 150 years ago that his creditors would be willing to roll over their loans indefinitely. In the event, they did not. Instead, they sent gunboats. For the next seventy years Egypt was under British rule.

That exact scenario is unlikely to be played out again, if only because gunboats are no longer necessary for debt collection. Hedge fund managers have demonstrated in various cases, of which that involving Argentinian sovereign debt is the most famous, that they can use international courts to seize assets to extract repayment.

Egypt's profound dependence for literally its daily bread makes it uniquely vulnerable to such financial pressures. So if Sisi's calculation is that he can stiff his creditors, he had better think again.

Robert Springborg is the Kuwait Foundation Visiting Scholar at Harvard University's Middle East Initiative, Belfer Center. He is also Visiting Professor in the Department of War Studies, King's College, London, and non-resident Research Fellow of the Italian Institute of International Affairs.

Opinions expressed in this article remain those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of The New Arab, its editorial board or staff

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News