Displaced Syrians go home to ruins rather than risk coronavirus

His home in volatile northwest Syria may have been destroyed, but Hassan Khraiby decided returning was better than risking his 10 children catch the coronavirus in a packed displacement camp.

"We were scared the coronavirus might spread because of the severe overcrowding," 45-year-old Khraiby says.

So, like others, "we decided to come home - even if our homes have been destroyed."

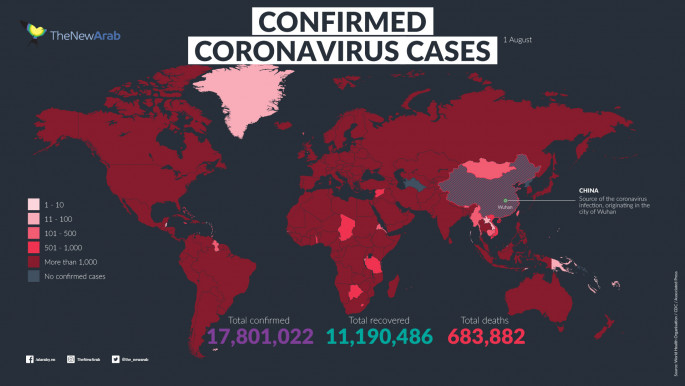

No case of the COVID-19 illness has yet been recorded in northwest Syria, but aid organisations fear any outbreak in the last major rebel bastion of Idlib would be catastrophic.

They warn the virus could rage through jam-packed displaced camps, where maintaining basic hygiene is difficult and social distancing near impossible.

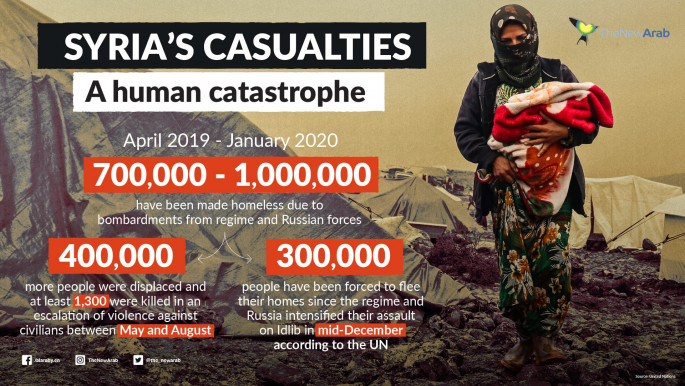

Khraiby and his family were among nearly one million to flee their homes during a deadly Moscow-backed regime offensive against the jihadist-dominated region from December - the largest such wave of displacement in Syria's nine-year-old war.

Now, just a few weeks into a fragile truce that took effect as the virus outbreak was turning into a pandemic, they are among hundreds to have returned to Ariha, some to stay.

In the town, children giggle as they scale mountains of grey rubble where buildings once stood.

In one bakery, flat circles of dough are loaded into a blazing oven, before being churned back out on a conveyor belt as piping hot loaves.

|

Regime 'too busy for us'

In one of the town's streets, Khraiby admires his parked water tanker.

"I've gone back to transporting drinking water to the townspeople," says the burly man, grey stubble framing his tanned face.

He says he and his family spent a month in a camp near the Turkish border before moving to expensive rented accommodation.

They decided to come home while the Russian-backed truce still holds.

When the ceasefire came into effect on March 6 in the wider jihadist-dominated region, weary residents were deeply sceptical it would last.

But it has so far, as Damascus grapples to contain a rising COVID-19 illness tally of at least 29 cases, including two deaths.

"Because of the coronavirus, the regime and Russia are too busy for us," Khraiby says.

"I hope they will be too busy for us for a long time."

Read more: Syrians forced to break coronavirus restrictions to feed their families

Nearby, Rami Abu Raed, 32, also believes the regime would have resumed military operations had it not been for the virus, and says the attacks will eventually restart.

The father of three returned to Ariha last week, fearing his children would contract the novel coronavirus in the camps further north.

"The north has now become so crowded. People are living on top of each other," he says.

"I was scared for my children so I decided to return to Ariha."

|

'Scared to come back'

Not far off, a few small trucks drive back into town, the odd mattress stacked in the back.

In one damaged building, workers lay cement cinder blocks in a gaping hole in a wall.

On the rubble of another, men swing sledgehammers at what remains of a collapsed top floor.

Yahya, 34, says he returned to help people rebuild their homes but is reluctant to bring back his wife and three children, or any of their furniture.

"People are scared to come back," he says, standing inside his small workshop, supplies hanging along the wall.

"At any time, the regime could break the truce, start advancing or bombarding us again."

In the town cemetery, 40-year-old Umm Abdu presses her forehead to the side of a tall white tombstone, a child in a face mask by her side.

Amid the wild grass and spring flowers, she says she has only returned to Ariha briefly to visit the graves of two sons slain during the war.

Read more: There's only one machine to test for coronavirus in war-torn Idlib

Along with her husband and five other children, Umm Abdu has lived in a mosque near the Turkish border for two months.

If the situation remains stable, the family plans to move back by the end of April, even though their home has been destroyed.

"Hopefully everything will go back to normal in our town and we can stay, and I can visit the graves of my two deceased children," she says.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News