Nile countries meet for high-stakes talks amid grave Egyptian fears over Ethiopian dam

The irrigation ministers of three key Nile basin countries have kicked off high-stakes negotiations in Cairo about Ethiopia's mega-dam project, which is nearly 70 percent complete.

Egypt says that Ethiopia's Great Ethiopia Renaissance Dam (GERD) threatens its water supply, and joined ministers from some Nile Basin countries on Monday, along with American and World Bank officials.

It will be the second round of technical talks on the dam issue since a breakdown in negotiations prompted Egypt to appeal for international mediation.

The White House stepped in last month, hosting the foreign ministers of Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan, who agreed to move talks forward.

Read more: Ethiopia's Great Renaissance Dam - A Catastrophe for Egypt?

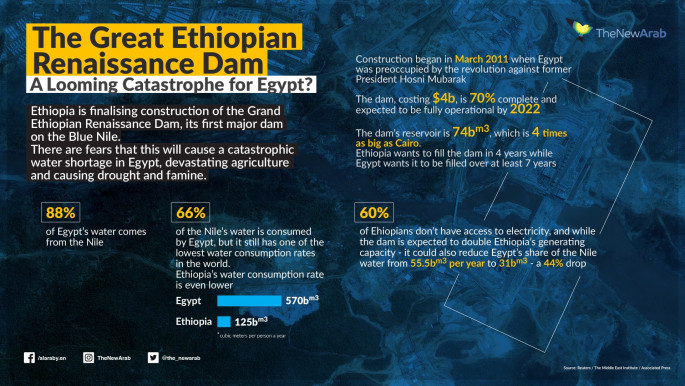

Ethiopia launched construction of its dam in 2011 and expects to begin generating power by the end of 2020 and to be fully operational by 2022.

Nine years of negotiations between the three countries have so far brought no deal.

Last month, Egypt, Sudan and Ethiopia agreed in Washington to hold a series of meetings to resolve the main points of contention regarding the filling and operation of the dam.

The three-way meetings - attended by World Bank and US observers - have set 15 January as a target to resolve the longstanding issue.

Months of meetings have so far failed to yield consensus on the dam’s most contentious issues, including a timetable for filling the reservoir.

Egypt fears Ethiopia's $5 billion project - set to be Africa’s largest hydraulic dam - could reduce its share of Nile water, which the North African nation's 100 million people are dependent on.

Egypt has for years been suffering from a severe water crisis that some analysts blame on population growth, and farmers try to make the most of the scarce water supplies.

Other factors include climate change drying up the Nile, and water pollution due to sewage discharge as well as industrial and municipal waste.

However, Egyptians consider Ethiopia's planned dam to be the most immediate threat, even though Addis Ababa says the GERD will not affect Egypt’s water supply.

"It will be devastation to all of us and our farmlands. How will we be able to sustain our businesses then? If we cannot support ourselves, how will the rest of the country find food?" said Ahmed, a 23-year-old farmer.

'A deal has to be reached'

Nearly 88 percent of Egypt's water supplies comes from the Nile and the currently consumes approximately 55.5 billion cubic metres of water from the great river.

The GERD could cut Egypt's share to 31 billion cubic metres, leading to a situation of "absolute water scarcity", according to the director of the Middle East Institute's Egypt programme, Mirette Mabrouk.

"A deal has to be reached. Otherwise Egypt will be prone to insurmountable social and economic risk," said Hani Raslan, an analyst at Al-Ahram Center for Political and Strategic Studies in Cairo.

"And this could eventually translate to political crisis and instability," he added.

Parched land, a fall in food production and an inability to generate electricity from Aswan's High Dam are a few risks, he said.

The Nile provides nearly 97 percent of Egypt's freshwater needs and its banks are home to some 95 percent of Egypt's 100 million population, according to the UN.

Even historians believe the country's ancient civilisation would not have existed if it was not for the Nile.

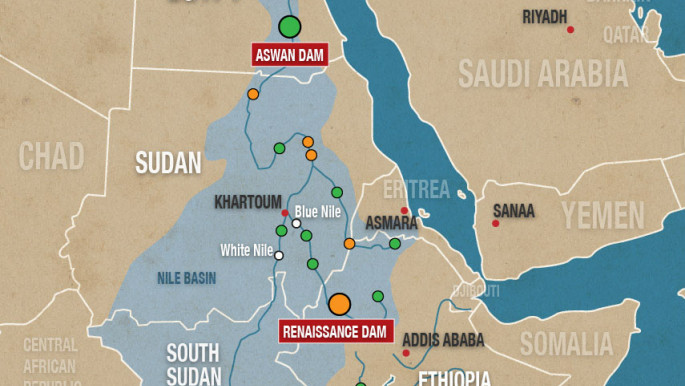

The river flows through 10 African countries. Its main tributaries, the White and Blue Niles, converge in the Sudanese capital Khartoum before flowing north through Egypt to drain into the Mediterranean Sea.

"Egypt's dependency on the Nile does not compare with other Nile-basin countries," said former irrigation minister Mohamed Nasr al-Din.

"We are far below water scarcity baseline," he added.

Scarcity and blame

Hydrologists say that people are facing water scarcity when the supply drops below 1,000 cubic metres per person annually.

Egyptian officials say in 2018 the individual share reached 570 cubic metres and is expected to further drop to 500 cubic metres by 2025.

In recent years, the government under President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi has been pushing for strict water conservation measures.

Those include installing water-saving taps at public facilities, recycling water and restricting cultivation of water intensive crops like rice.

However, Sisi has been criticised by Egyptians for his handling of the crisis with many Egyptians saying that he hasn’t done enough to protect Egypt’s water supply.

In October, Mohammed Ali, a dissident construction contractor who had previously revealed that Sisi had been using public money to build luxurious palaces for himself even called for the execution of the president and his ministers for treason over the matter of the Nile.

Ali said that the autocratic president had "kept Egyptians in the dark" about the dangers of the Ethiopian dam.

Ethiopia says its $4 billion structure is indispensable for economic development and providing electricity.

And for Sudan the dam would provide electricity and help regulate floods every rainy season.

Despite increased tensions, analysts have dismissed the possibility of armed conflict.

It is "highly unlikely as it would be enormously damaging for all sides," said William Davison, a senior analyst at Crisis Group.

But the possibility stands "that the US government applies pressure on the parties to reach an agreement", he added

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News