Debt spiral engulfs Turkish voters months before polls

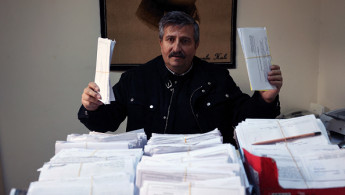

The growing pile of debt notices covering the Ankara district mayor's desk hints at the scale of the economic crisis facing Turkish voters months before crucial presidential polls.

The warnings and court summonses end up being forwarded to Ali Golpinar -- the "muhtar" of one of the Turkish capital's working-class suburbs -- when they cannot be delivered to the debtor's stated address.

Golpinar says the number of them he gets daily has doubled to about 40 in the past two years.

That generally reflects what has happened to Turkey's consumer prices over the same span. The official inflation rate hit 85 percent in the past year alone.

"And these are only the undelivered letters," Golpinar said from behind his messy desk.

"Imagine how many there are in all. People can no longer pay their debts."

Turkish media say the total number of debt recovery cases rose by about 1.5 million in a year and exceeded 24 million at the height of the crisis in August.

The main banking regulator says the value of unpaid individual loans in the nation of 85 million people rose from 17 billion to 29 billion liras ($1.6 billion) between March and September.

Debt dilemma

Economist Erinc Yeldan said Turkey was experiencing fallout from a years-long policy that encouraged cheap lending to achieve rapid rates of economic growth.

Turkey's growth continued throughout the coronavirus pandemic and reached 11 percent of gross domestic product in 2021 -- the highest rate among the Group of 20 major economies.

Erdogan cites these figures while promoting a "new economic model" built on domestic production and exports.

"Turkey has voluntarily increased its foreign and domestic debt," Yeldan said.

The main opposition CHP party's anti-poverty campaigner Hacer Foggo said this policy allowed people without fixed incomes to obtain cheap loans.

These same people "are facing the dilemma of choosing between paying their rent, taking their child to the doctor or repaying their loans," she said.

City governments run by the opposition -- including Ankara and Istanbul -- have set up websites that take donations to help the needy pay their utility bills.

Erdogan's government is also announcing a steady stream of populist measures entering the election campaign.

One of the latest involves pushing creditors to cancel debts of less than 2,000 liras ($105).

These announcements have helped prop up Erdogan's sagging numbers as he tries to extend his rule into a third decade in what promises to be a tight vote.

But Golpinar said he is yet to hear of anyone who has filled out all the paperwork needed to get a debt writeoff.

"I don't know of a single person who has benefited from it," the district mayor said.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News