Exclusive: How Russia swooped Syria's hydrocarbon share in the Eastern Mediterranean

An investigation by The New Arab’s sister site Al-Araby Al-Jadeed dug deeper to reveal Soyuzneftegaz's operations in Syria, its questionable credentials, links to corruption and hidden manoeuvres with the Assad regime, in what appears to be another bid by Russia and its cronies to increase their influence over Syria's wealth and resources.

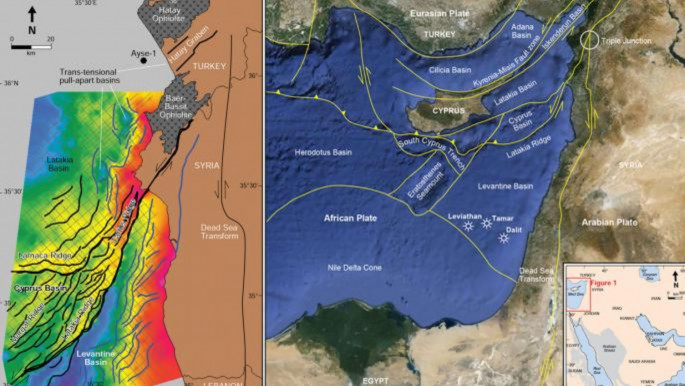

Hydrocarbon reserves in Syria territorial waters

In 2005, the Norwegian company Inseis conducted seismic surveys on Syrian territorial waters, and the subsequent report, published by French company CGGVertitas in 2011 following its acquisition of Inseis, showed "encouraging results'' of oil and gas reserves off Syria's coast.

By 2010 however, a US Geological Survey had already estimated 1.7 billion barrels in undiscovered oil and 122 trillion cubic feet of natural gas in the so-called Levantine Basin, off the coast of Syria, Lebanon and Israel along the Eastern Mediterranean.

|

| Click here to enlarge |

While Syria's ministry of petroleum and mineral resources did not then provide any information about confirmed reserves, the state-run Al-Thawra newspaper reported in 2013 that the Syrian share is estimated to be 6.5% of the total area of the Levantine Basin.

By the time the surveys were complete however, the Syrian government had already set gears into motion to begin exploration. In May 2007, Syria's oil ministry introduced four offshore sectors for exploration, but then only the British company Dove Energy applied. Their sole offer was rejected as it was without competition.

On March 24, 2011, Syria put forward a tender for oil exploration in the four offshore blocks, with an area of 7,750 sq km. This time no offers were received, despite the extension of the deadline. A month later, the former Oil Minister Sufian Allaw would allege that the country's complex political situation deterred companies from applying.

Two years on however, things changed dramatically. The state-controlled Russian group Soyuzneftegaz swooped up an energy deals that would further influence the strategic calculations underpinning the civil war in Syria, and which allowed Russia to exploit offshore oil and gas deposits off the East Mediterranean coast.

Credentials for offshore exploration

On December 26, 2013, the Syrian regime and Russia's Soyuzneftegaz signed a deal that allowed for exploration, drilling, development and production of oil and gas in Block 2 – a 2,977sq km area off Syria’s coast, at a cost of $100 million.

However, an official document issued by Syria's oil ministry, leaked in November 2013, cited a senior ministry official as saying that Soyuzneftegaz's profile suggests that the company does not have capacity for deep offshore exploration. Although Soyuzneftegaz had, since 2003, signed contracts to excavate in Iraq and Syria, it has only worked onshore and had not drilled an offshore well since its establishment.

|

| Syria's Minister of Petroleum and Mineral Resources Suleiman Al Abbas (R) and Ambassador of Russia in Damascus Azamat Kulmuhametov (L) hold a press conference after signing oil exploration deal with Russian firm Soyuzneftegaz in December 2013 [Getty] |

Experts warned that the company is an oil and gas trading company, and has no experience in discovering or extracting activities.

International expert Mahmoud Salameh - a researcher specialising in energy affairs at several bodies, including OPEC, the World Bank and major international universities - said that despite the participation of Soyuzneftegaz in managing energy projects in Russia and around the world, it remains "a service company, like Halliburton or Schlumberger" – both oil field service companies. Salameh added that as a result, Soyuzneftegaz was likely to "only have an advisory role" in the exploration for oil and gas in Syrian waters.

"It is likely that the Russian government will ask major Russian oil and gas companies such as Rosneft and Gazprom to carry out real excavation and drilling at a later stage," Salameh said, referring to Russian companies that specialised in oil and gas exploration.

Al-Araby Al-Jadeed contacted an official who had a senior role in the Syrian government at the time when the contract with Soyuzneftegaz was signed, and who agreed to comment on condition of anonymity.

The official asserted that the deal with the Russian company "lacked scientific logic", adding that the contract with Soyuzneftegaz had "more political" implications than it did economic benefits for Syria.

|

Experts warned that the company is an oil and gas trading company, and has no experience in discovering or extracting activities |  |

Evading sanctions

In July 2014, Syria's Official Gazette published the official agreement, entitled "Ratification of the contract between Syria and Soyuz Panama for oil exploration". It appeared that the deal was signed between the Syrian government and the Panama-registered Soyuzneftegaz East Med, rather than with the main company in Russia.

In August 2017, the Syrian regime issued Decree No. 27, approving an amendment to the contract with Soyuzneftegaz. It referred to the sub-company with a new name; East Med Amrit S.A. It also changed the origin of the company from "Panamanian" to "Russian".

The threat of new sanctions imposed by the US through the Caesar Act, which was signed into law in 2019 and came into force in 2020 and which would penalise any foreign entity dealing with or supporting the Syrian regime, meant that Russia could not risk subjecting its top energy companies to sanctions.

Experts say the deal with Soyuzneftegaz and subsequent changes to name and origin of the sub-company were designed to create a front to protect Russia's top energy companies, which would actually carry out the oil exploration. This example, experts say, reveals the increasing influence of Russia over Syria’s wealth and resources, and their techniques to circumvent the US sanctions.

International oil economist and World Bank consultant Mamdouh Salameh believes that Russia would not risk subjecting Rosneft and Gazprom to sanctions, adding that the two companies will begin oil exploration directly after the sanctions expire.

Russia's military intervention in Syria has cost it billions of dollars, so it has signed contracts to recover this money from gas and oil discovered in future, Salameh added.

Numerous attempts to contact Syria's oil ministry asking for clarification over the change in company name on the contracts went unanswered. Similarly, Soyuzneftegaz has not responded to a request for comment.

|

|

Yuri Shafranik has had a close relationship with authorities in Moscow |

Concealing identities

Soyuzneftegaz was established in 2000. The head of the company, Yuri Shafranik, is a Russian citizen and public figure who has had a close relationship with authorities in Moscow since the mid-90s. He served as energy minister under Boris Yeltsin, between 1993-1996, and is currently the chairman of the board of the Union of Oil and Gas producers of Russia.

In Iraq, he is attested to be a key figure among the circles of former PM Nouri al-Maliki and helped Russia land a $4 billion arms contract with the authorities in Bagdad. An investigation into the UN-led Iraq oil-for-food programme found that he had received 25.5mn barrels of Iraq oil, which was later remarketed and sold in European markets.

Unlike Soyuzneftegaz, the sub-company East Med Amrit S.A does not have a website or any published public data. Al-Araby Al-Jadeed obtained its registration document, which show it was registered in Panama in September 2013 – only three months before signing the contract with the Syrian government.

The documents also showed that the company changed its name to East Med Amrit S.A in October 2015 and added 100 shares at a value of $1,000 each, making the company's capital $100,000.

The names of Shafranik and Gissa Gutchel, Soyuzneftegaz’s executive director in Syria, were however absent from the company documents relating to East Med Amrit S.A. The company was registered in the name of Panamanian national Vernon Emmanuel Salazar Zurita. His name resurfaced after the Panama Paper leaks, before he was arrested over alleged seizure of public funds.

In 2018, Delio Jose De Leon Mela was registered as company deputy director. Following the the Panama leaks, it emerged that his law firm Quijano y Asociados, had created 15,000 companies. In December 2019, Jose was investigated over his company's involvement in a corruption scandal in Colombia.

Soyuzneftegaz's executive director in Syria, Gissa Gutchel, was the Russian who signed the exploration contract with the Syrian government back in 2013. According to the Institute of Oriental Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Gutchel holds a PhD in history; not in management or energy sciences.

Guchtel's name also appeared in the Offshore Leaks and Panama Papers, which linked him to companies registered in tax havens. He was registered as the owner and director of Dexwood Global Investment Limited, an investment company that was active in the British Virgin Islands and in Latvia. Current data shows that the company is no longer active, but two of its subsidiaries continue to operate in Latvia.

Guchtel was also a partner with British businessman Ian Taylor, who died in 2020 and whose history was marked by controversy, with accusations of dealing with Serbian war criminals during the Bosnian war and the involvement of his company Vitol Group in the corruption scandal relating to the Iraq oil-for-food programme.

|

Russia's military intervention in Syria has cost it billions of dollars, so it has signed contracts to recover this money from gas and oil discovered in future |  |

Exploration halted

About 18 months after signing the oil exploration contract, Soyuzneftegaz decided it will no longer be able to meet its contractual agreement in Syria.

Shafranik announced in September 2015 that his company will "not to proceed and abstained from active participation in the offshore project in Syria", citing the civil conflict. Shafranik said the project would be passed on to a Russian energy company, which he did not name. It would later emerge that the company is East Med Amrit S.A.

A communication from Syria's Oil Minister Ali Suleiman Ghanem to former Prime Minister Imad Khamis indicated that Soyuzneftegaz stopped its work due to force majeure and had been carrying out most of its contractual obligations between 2013 and 2014.

The communication, which was reported by the official Al-Ba'ath newspaper, contradicted Decree No 31 of 2011, which stipulates that a minister cannot ratify investment contracts with values exceeding 200 mn Syrian pounds ($160,000 USD) without parliamentary approval. The contract between Syria and Soyuzneftegaz was therefore unlawfully amended in 2014, when the name of the Russian company was changed by ministerial approval alone.

A further amendment, Decree No 27 of 2017, would give the Russian company rights to proceed, provided that the exploration period is limited to 60 months from when the works begin and not from the date the contract was signed. The contract would later be extended by another 20 months, for a total period of 80 months.

The amendments demonstrate the extent to which the Syrian government is willing to bypass its own laws to trade Syria's economic potential for Russian support for its authority.

Eight years have now passed since the deal was signed and the Russians managed to get their hands on Syria's share of the oil and gas in the Eastern Mediterranean, without any declaration of the results of exploration works carried out.

This article is a translation of the original Arabic investigation that appeared on Al-Araby Al-Jadeed's website, which can be found here.

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram to stay connected

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News