Ethiopia's Great Renaissance Dam: A catastrophe for Egypt?

This was the second of a series of four meetings regarding the huge dam Ethiopia is building on the Blue Nile.

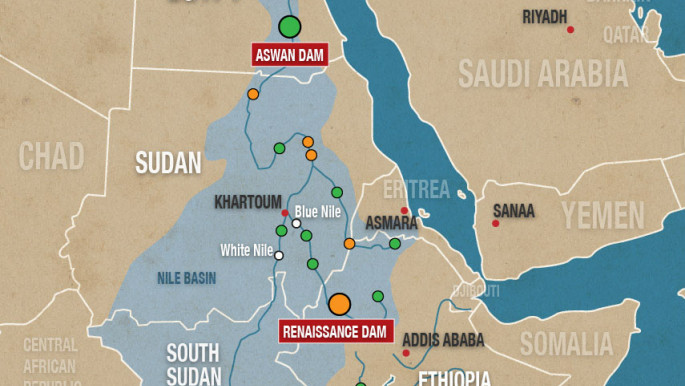

Ethiopia sees the Great Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) as a vital project for its future development. However, the dam will potentially reduce the amount of Nile water flowing to downstream Egypt.

Egyptians fear that it will have a catastrophic impact on their country, depriving them of the water they need for drinking and growing crops, and possibly causing famine and drought.

Read also: Who is losing the Nile?

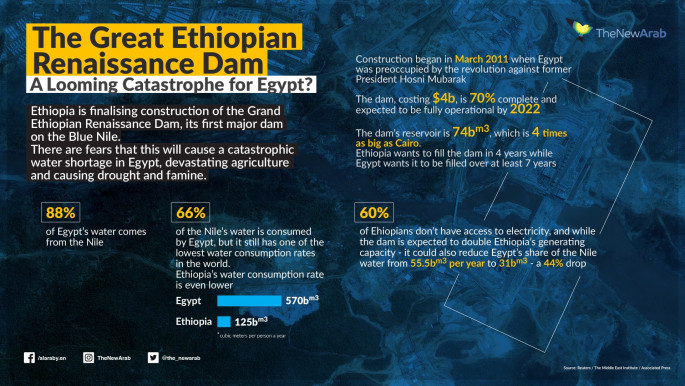

Throughout its history, Egypt has been dependent on the Nile and this dependence has not reduced in recent times. Nearly 88 percent of Egypt's water supply comes from the great river and more than 85 percent of the Nile water flowing to Egypt comes from Ethiopia.

Egypt already has one of the lowest per capita water consumption rates in the world, at 570 cubic metres per year. The global average is 1,000 cubic metres per year. Ethiopia, however, has an even lower per capita consumption rate than Egypt, at 125 cubic metres per year.

There are international agreements regulating the amount of Nile water Egypt receives. A 1959 treaty between Egypt and Sudan gave 55.5 billion cubic metres of water to Egypt and 18.5 billion cubic metres to Sudan. But the upstream African states where the Nile originates from, including Ethiopia, were not a party to these agreements. Ethiopia has never recognised the Egyptian-Sudanese agreement and until construction of the GERD began in March 2011, Ethiopia was unable to effectively use the Nile's water.

This has been seen as a source of shame and a signifier of underdevelopment in the country where most of the Nile's water originates.

A history of conflict

Egypt and Ethiopia have clashed over the Nile long before the building of the GERD began. In 1874, Egypt, which controlled most of Sudan at the time, invaded Ethiopia in an attempt to gain control of the source of the Blue Nile. Egypt's ruler at the time, Khedive Ismail, aimed to bring all the sources of the Nile under Egyptian control. However, in the resulting war, Egypt was defeated by the Ethiopian army.

In the 20th century, Ethiopia's exclusion from the 1959 agreement soured relations between Egypt and Ethiopia. When Ethiopian emperor Haile Selassie began planning dams on the Blue Nile in the 1960s, Egypt provided support to rebels in Eritrea, which had recently been annexed by Ethiopia and ultimately became an independent state in 1993.

In 1979, after the signing of the Camp David Peace Treaty with Israel, Egyptian President Anwar Sadat said, "The only matter that could take Egypt to war again is water", in a clear message to Ethiopia and other upstream Nile countries.

|

|

| Read more: Who is losing the Nile? |

Work on the GERD began in March 2011, when Egypt was preoccupied with the revolution that overthrew longtime dictator Hosni Mubarak.

Mirette Mabrouk, the Director of the Egypt Programme at the US-based Middle East Institute (MEI), says that the GERD "has the capacity to essentially turn the taps off in Egypt". She points out that there has been no environmental impact study on the GERD, as required by international law.

The exact effect the GERD will have on Egypt remains unclear. However, nearly all Egyptian observers agree that it will be negative, with many saying that it will be catastrophic.

Sudan, on the other hand, is today supportive of Ethiopia's goal of building the dam, which is just twenty kilometres from the Ethiopian-Sudanese border. Sudan believes that the GERD can improve the functionality of its own Nile dams and regulate flooding and irrigation.

Mabrouk says that Egypt's water consumption per capita is likely to drop from 570 cubic metres per person per year to 500 cubic metres as a result of the dam, a figure that represents "absolute water scarcity".

|

|

No guarantees

Currently, Egypt and Ethiopia are arguing over exactly how much water Egypt will receive after the GERD is constructed and the rate at which the GERD will be filled.

Egypt wants a guarantee from Ethiopia that it will receive 40 billion cubic metres of water from the Nile after the GERD is constructed – much less water than what it receives today – and also wants the GERD to be filled over a time period of at least seven years. Ethiopia, on the other hand, has only been willing to guarantee Egypt 31 billion cubic metres of water and wants to fill the dam and bring it to full operation over four years.

Last month an Egyptian irrigation official told the Associated Press that unless the GERD is filled slowly and Egypt receives a guaranteed 40 billion cubic metres of water from the Nile, the effects will be catastrophic, impacting on Egypt's own Aswan High Dam, which generates most of the country's electricity.

"It could put millions of farmers out of work. We might lose more than one million jobs and $1.8 billion annually, as well as $300 million worth of electricity," he said.

Both countries toady say that they are committed to resolving the issue of the GERD through negotiation, but this has not removed the possibility of war and conflict and bellicose rhetoric is still being used by the two sides.

Negotiations between Ethiopia, Egypt, and Sudan have been ongoing since 2014. Last October they broke down before resuming again following US intervention.

Ethiopian Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed said in October that his country was willing to mobilise an army of one million people to defend the GERD if it came to war, saying, "No force can stop Ethiopia from building the dam". His statement came just days after he was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his efforts to achieve peace with Ethiopia's neighbour Eritrea.

|

The GERD is expected to generate 6,400 megawatts of electricity in a country where 60% of the population currently have no electricity |  |

The GERD is expected to generate 6,400 megawatts of electricity in a country where 60 percent of the population currently have no electricity. Ethiopia believes that this will have a transformative effect on its economy, helping it achieve its goal of transitioning from a low to a middle-income country.

Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi said last month at the UN that he would "never" allow Ethiopia to impose a "de facto situation" by unilaterally filling the dam. "While we acknowledge Ethiopia's right to development, the water of the Nile is a question of life, a matter of existence to Egypt," he said.

Sisi and the Ethiopian Fait Accompli

While Sisi's UN statements about the GERD may make it seem that the Egyptian government is determined to protect Egypt's share of the Nile's water, the autocratic leader has been criticised by Egyptians for his perceived inaction regarding the dam.

Mohamed Ali, a dissident construction contractor who in September revealed that Sisi had been using public money to build luxurious palaces for himself, said in a video in October, "[Sisi] signed an agreement and told us not to worry and there wouldn't be a problem. He spent four years keeping us in the dark and telling us everything is fine."

Ali even called for the execution of the president and his ministers for treason.

Ahmed Aboudouh, a consultant editor for the UK newspaper The Independent says that the dispute over the GERD had "shown how Egypt had fallen off the world stage" and that its presence in Africa and the Middle East had "shrivelled" in recent years. He added that the defiant rhetoric coming out of Ethiopia regarding the dam would have been "unimaginable" ten years ago.

Ethiopia today has effectively presented Egypt with a fait accompli regarding the GERD. Seventy percent of the dam is complete and while there have been loud protests and threats of war in Egyptian media, official reaction seems to have been relatively muted, despite Sisi's UN announcement.

Writing for the New Arab's Arabic language sister site, Dr Abdul Tawab Barakat, an Egyptian agriculture specialist said in October, "Sisi has not been open with Egyptians regarding negotiations with Ethiopia which have been ongoing since 2014, nor the dangers of the failure of these negotiations for Egyptian water security. It's only the Egyptian people who will suffer the consequences of this hostile dam."

Sam Charles Hamad, a Scottish-Egyptian activist and writer told The New Arab, "Without the Nile's productivity, both natural and man-made, Egypt is facing a major crisis. One study predicts that over half of Egypt's farmland would be wiped out as a result of the dam, which would of course lead to huge food crises – you're talking about famine here.

"You can imagine the kind of crisis that would erupt if there were water shortages, food and power shortages – huge civil unrest and potentially horrific responses from the regime."

|

One study predicts that over half of Egypt's farmland would be wiped out as a result of the dam, which would of course lead to huge food crises – you're talking about famine here |  |

While negotiations are still ongoing and both Egypt and Ethiopia say that they are determined to find a solution acceptable to both sides, the effect of the GERD on Egypt is unlikely to be anything other than negative. The fact that Ethiopia has been able to nearly complete the dam and brush off the threat of war with Egypt has shown Egypt's declining power on the world stage under President Sisi.

While the dam will help Ethiopia prosper and develop, this could come at a ruinous cost to ordinary Egyptians and create hardship and instability in a country already suffering under an autocratic regime.

Amr Salahi is a journalist at The New Arab.

Follow us on Twitter and Instagram to stay connected

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News