Syrian refugees in Lebanon weigh the risks of returning against the risks of staying

Sun filters down through the leaves, leaving a patchwork of dappled shade across his body, drawing his face in and out of the light. The small garden around us is bursting with life.

Abu Saleh is from Eastern Ghouta, the oasis at the doors of Damascus. He fled to Lebanon in 2014, watching the siege and destruction of his home from a garage in the Beqaa Valley. Today however, he speaks about returning.

In April 2018 the Syrian government passed law No.10 to regulate reconstruction zones across Syria, forcing citizens to provide proof of property ownership to avoid government confiscation of land and homes.

Screening his phone from the sun, he shows us videos of his family home sent to him by his neighbour just a few days ago. The interior is in ruins, no piece of furniture intact.

"Shabbiyah [informal militias loyal to the regime] passed by last week," he says. He points to the burnt walls shown on the screen. "They put expandable foam and oil onto the walls before setting them alight." He continues, lighting a cigarette, "we're lucky though, at least we still have a home standing. I can't lose that too".

The past few months have seen a growing number of refugees in Lebanon returning to Syria, leading Russian envoys to claim that government-controlled areas are now safe for returnees. In July the Syrian regime made its first formal appeal for the return of refugees, opening reception centres to monitor return: a move many interpreted as a bid to regain international legitimacy.

However, according to UNHCR, conditions are not yet ready for the return of refugees to Syria, especially while the siege on rebel-held Idlib continues. Even in regions where armed clashes and bombing have reduced, imprisonment, forced conscription, and a lack of basic primary services make safe return for Syrians premature.

As Abu Saleh talks of return, others already have made the journey. We meet Sheik Ahmed in his home, the basement of a small block of flats close to Halba, in northern Lebanon, a few kilometres from the Syrian border.

|

They invent the charges and there is nothing you can do about it |  |

His 74-year-old father, Walid, returned to Syria three months ago to register their property in Homs, one of the few still standing in his neighbourhood.

Believing that going through army checkpoints would be safer for an old man like his father, Sheik Ahmed encouraged his temporary return. Instead, Walid was arrested at the border by the shurta ashkariya (military police), and taken to a prison in the outskirts of Damascus.

Sheik Ahmed speaks in fast fusha, his hands anxiously rubbing his knuckles.

"When we realised he had disappeared, we had to pay $500 to an officer at the checkpoint only to know to which prison they had taken him."

It took a further two months to receive any more news, and more than $5,000 to secure his release. Lowering his voice, Sheik Ahmed outlines the workings of a well-functioning blackmail system.

|

|

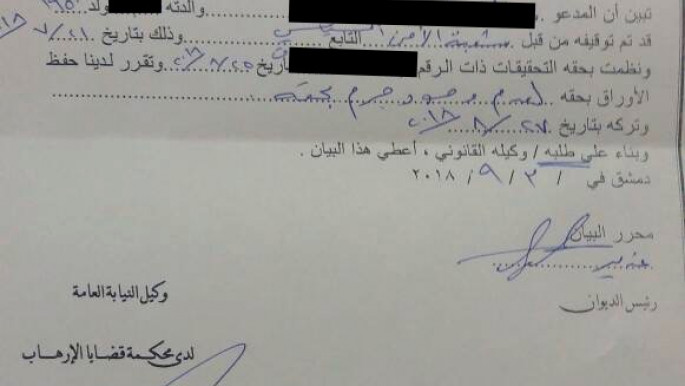

| Bail paper from Syrian authorities [Obtained by The New Arab] |

"The judge sets a price on each detained prisoner according to the charge and to their knowledge of the prisoner's family's wealth."

Walid was charged with terrorism and weapons smuggling.

"How can a man of his age be charged with such accusations?" asked his son.

Walid had left Homs with the whole family in 2012, after witnessing the massacre of Houla while visiting a nephew. He hadn't returning to Syria since.

"They invent the charges" Sheik Ahmed continues, "and there is nothing you can do about it."

Despite his old age, Walid was held for a total of 50 days, spent either in isolation, hanging with his arms chained to the ceiling, or in small cells with a dozen other detainees.

"They keep you alive only if you are innocent. Because they know they can blackmail your family for money."

Sheik Ahmed was able to collect $5,000 from family and friends in Lebanon, and send them to the other side of the border through a trusted friend.

"Half of that money will go to the general in charge of the prison, the other to the judge. It's a way for the regime to reward its cronies," he said.

Sheik Ahmed's family had to pay another $200 to have an official letter declaring Walid was innocent of all charges. It is not unusual to hear similar stories, but what made Walid's unique is that he had saved the paperwork as evidence.

The risks of return, however, have to be measured against the risks of staying.

Life for Syrian refugees in Lebanon is worsening as the country's economy declines.

The cuts to humanitarian aid agencies, drained seven years after the start of the crisis, has only made the situation worse.

Paola, a volunteer working with Operazione Colomba's four year presence in the camps, explained how there used to be much more support for refugees here:

"In 2012, the UN and INGOs arrived here full of money to spend on humanitarian programmes. Everybody was donating. Seven years on, they are reducing budgets. The situation is so critical that refugees have started taking the sea routes [to Europe] again."

Just a week ago, a boat carrying at least 39 people capsized just off the coast of Akkar, killing a woman and a small child as refugees tried to reach Cyprus.

Read also: 'The remedy of a soul': Mental health worker Hadeel Naser helps Syrian refugees heal

Authorities said this was a unique attempt in the past year. But as Lebanese politicians push for return, refugees are increasingly willing to look for alternatives to potential future forced repatriation schemes.

Even without the threat posed by repatriation, life in Lebanon is harsh enough to push people to consider return. While the UN provides support for many primary medical needs, many illnesses, including any chronic conditions, cannot be treated effectively.

One young family from Quasyr in Syria decided to return because their eight-year-old son Hussein had liver cancer and they could not afford his treatment in Lebanon.

"We cannot just sit and watch our son die," Hussein's father told The New Arab over the phone. "We must do something even if that means returning to hell."

|

We cannot just sit and watch our son die. We must do something even if that means returning to hell |  |

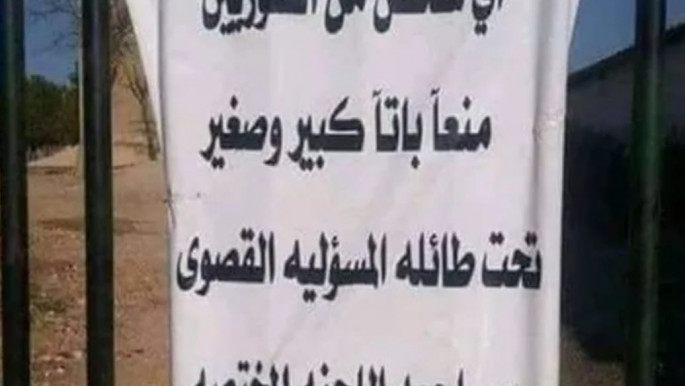

The impossibility to regularise their status to legally reside and work in Lebanon puts most Syrian men at risk of preventive arrest any time they cross a checkpoint. As curfews in mountain villages are getting stricter, signs forbidding the burial of Syrians have appeared around Beirut and in the northern regions, evidence of growing discrimination adding to episodes of violence.

|

|

| Forbidden to bury Syrians: "It is strictly prohibited to bury and Syrian no matter how old or young, under strict personal accountability and authorisation by the designated committee." |

With continued internal displacement still outpacing returns, the question around re-population is key to any attempt for a political solution to the conflict.

More than six million refugees currently reside in Syria's neighbouring countries, while another 6.6 million people are internally displaced.

Reports of population shifts are rife among the Sunni refugee population, with accusations of regime-sponsored "double citizenship" awarded to Iranian and Lebanese fighters moving to Syria in an attempt to erase former bastions of opposition.

As the Syrian regime and its allies regain territory, immediate return for those who ran away from Syria's destruction is a far-fetched solution.

Most refugees are unwilling to return without a political transition and minimal guarantees of safety and livelihood.

At the same time, it's hard to imagine how millions of Syrian refugees will be able to continue living abroad with reducing aid, opportunities and rights.

Restrictive policies in Lebanon and elsewhere might force refugees to choose between return to war-torn Syria and the re-opening of dangerous migration routes to Europe.

|

This article is the first in a six-part series investigating the issues of return of Syrian refugees from Lebanon |

Roshan De Stone is a human rights advocate working in Syrian refugee camps in Lebanon. She is a full-time contributor to Brush&Bow.

David L. Suber is a political researcher and journalist. He is directing a documentary on deportations from Europe and currently lives in Lebanon, where he works in refugee camps. David is also a full-time contributor to Brush&Bow.

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News

Follow the Middle East's top stories in English at The New Arab on Google News